Willy Chavarria — For Us, By Us

This story appears in Justsmile Issue 3, Reflections are Protections.

Photography Casanova Cabrera

Styling Raymond Gee

Text M-C Hill

Willy Chavarria photographed in Brooklyn, New York

by Casanova Cabrera.

One Mamiya medium format and one Polaroid Instant camera lens the Willy Chavarria picture show. While both objects work to frame the ethereal against candid moments – a Felipe Merida portrait behind Chavarria’s workspace helps explain the methods behind all this fashion madness. Merida is a Guatemalan artist who dives deeply into moments of cultural community. While Merida regularly paints pictures of pop cultural iconography, this particular image is from a series on Hasidic Jewish people in Brooklyn, all done with a ballpoint pen. The Orthodox aspect is apparent; as is the obvious orthodoxy these two share. Like Merida, Chavarria deftly bounces between pop, Latinx and queer arenas, to tie an outward-facing story into fashion contexts. Chavarria’s own collections then balance multiple levels. Whether an entendre or business strategy, his fashion sandwich cookie remains gold on one side with chocolate contrasting the other.

There is something striking about native California fashion designers. Chavarria was born in Fresno, which is one hour away from Porterville, where Rick Owens grew up. The designer Shaun Samson is from San Diego. Then you have Matthew Williams from Pismo Beach. Each represents dueling characteristics. Owens juxtaposes brutalism against drag; Samson pits 808 bass chulo memories opposite a sexy skate/surf aesthetic; while Williams mixes Hells Angels with The Lost Boys mentality. As those visual proposals shift, move forward to transition and transmutate annually, seasonally is where their ideas evolve. Chavarria thinks those contrasts are implanted first in the soil, then into their souls. ‘California is spread out. There are pockets of extremely different communities all in one state – one city is hard core Republican, another city can be 100% Mexican,’ he explains. ‘Then you see watermelons rolling through the streets. Because they are so far apart, these small towns breed people who are very creative. These crazy visions are completely inspired by the surroundings you work with. That's the contrast. And when there is an opportunity, these people skyrocket out of their environments and go create. Their imagination saves them from going insane.’ Chavarria’s evolution remains grounded in characteristics which, when you really think about it, boil down to kindness, consideration … and cocks.

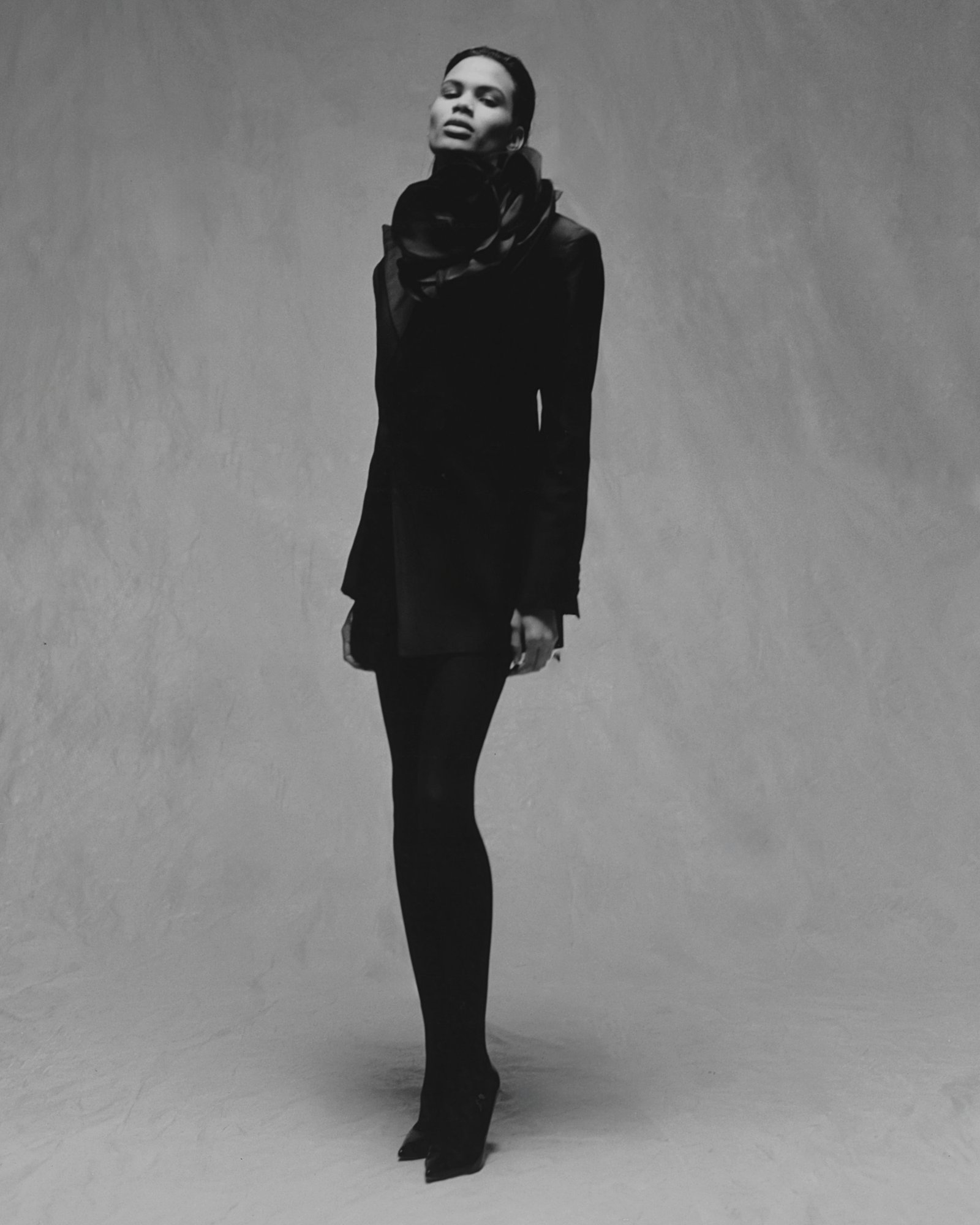

Thursday wears blazer, pants, scarf and gloves WILLY CHAVARRIA Fall/Winter 2023.

Let’s flashback to the 1990s: Joe Boxer underwear. When Willy Chavarria’s cheeky side infiltrated campy innuendo within Joe Boxer-branded underwear, their ads and all those buff bodies. Models affected properly homosexual gestures but were they really, you know? Those Joe Boxer campaigns reek of gay subtext. Call them the original power bottom. Notice where the tongue on those smiles were located. Joe Boxer becomes an irreverent image search to understand how Chavarria, their designer then, approaches his own work now. ‘I was a huge fan of Franco Moschino back then. It was kind of the first time you were seeing humor taking the piss out of fashion. Kind of like how putting happy faces on boxer shorts was a very big deal.’ As Chavarria started on the apparel side, that foundation became a discipline. Therefore, he manages the industrial fashion area easily. ‘I took the longer road to knowledge, you know. I've worked in places and learned a lot. So many designers today are hopping into it blindly, without realizing the intricacies of what needs to lie beneath. You could have an amazing message and collection without a long-term business structure. I took the longer path working in places and got to learn that.’

Now, the WC’s Brotherhood collection (Spring/Summer 2019) best represents his special sauce, which pours homoerotic signals onto fashion apparel’s blunt proficiency. Chavarria’s overt mix of sweat and sport had the palpably seductive appeal of an Original Yellow Timberland worn over a hairy, tanned footballer’s calf. His celebrating totemic New York maleness turned recognizable codes of street culture inside out. By taking those historic logos worn by East Coast rap icons; perforating workwear definitions from Dr. Dre, Snoop and Ruff Ryders into Tupac's sensual-cum-sexual territory, Chavarria redesigned a certain attitude. ‘The show opened up with guys who play football, and I love that aspect,’ he recalls. ‘Then, I took east L.A. California with the New York Uptown vibes and mashed them up too. Those Polo Ralph Lauren graphics multi-printed on tops and bottoms, I just thought that was such fun.’

Yuji wears t-shirt and shorts WILLY CHAVARRIA Spring/Summer 2023. Socks FALKE. Shoes stylist’s own. Necklace model’s own.

The Hong Kong model Wilfred Wong (look three in ‘Brotherhood’) typifies the ‘fun’ Chavarria relishes — an inclusive maleness that does not shy away from kitsch nor camp, it is brazenly unafraid of simply being. ‘Brotherhood happened during a time when hardcore macho, cisgendered, was considered toxic masculinity. It was a big no-no. In everyone's shows, even now, when you see queer culture, it's usually a feminine-leaning kind of identity. I am not shy of masculinity, that can be just as gay as a wig and heels, you know?’

Thursday wears trousers, boxers and belt WILLY CHAVARRIA Spring/Summer 2022.

In the Chavarria collections Real Men (Fall/Winter 2021) and Uncut (Fall/Winter 2022), he screams about what is taboo to say anymore: the urban silhouette. This is the silhouette we grow up with. We wear the oversized silhouette as BIPOC people do. This is what we work with. Our muscle memory gains real power when fashioned on the runway. It elevates us and educates people that never understood it. For those who live it (and live through it) well, this is simply Chavarria upholding our language. It is not Givenchy’s provenance. It is ours. ‘It’s a political thing, you know. The idea of space. The space that we take up. The space that we've been robbed of over time. This claiming of territory is something that I've always interpreted. Similar to gang culture where it's about claiming space in a city. It's all connected,’ he says. ‘So when I do those silhouettes it is claiming the fact that we are here and in the most beautiful way possible. So when you walk down the street with a Claude Montana shoulder, you do it with the confidence of owning your area.’ When Chavarria incorporates ideas that weave fashion into ours, using that Montana shoulder, then you begin to course correct mis-messaging within both histories.

Thursday wears shirt WILLY CHAVARRIA Spring/Summer 2022. Trousers WILLY CHAVARRIA Fall/Winter 2022. Shoes archive HELMUT LANG courtesy of Dominik Halás.

Chavarria’s foundational blueprint celebrates high-waisted, sharply pleated trousers – famously worn in the 1940s by Pachucos, Mexican-American youths inspired by 1920s jazz-era fashion. ‘That signature trouser really is the brand heritage,’ he says. Their electricity comes from harnessing World War II, anti-patriotic attitudes that white, male soldiers and civilians assaulted onto young Mexican-Americans from East Los Angeles. Think of Henry Reyna from the film Zoot Suit who embodied Pachuco's brash fabulousness and white fears that incited violence. Chavarria reverses transgressions. Extreme offenses — being beaten, stripped, having your clothes pissed on — cuts deep. Perhaps that is why Chavarria’s fashion also represents Brown and Black positivity as an acute provocation. Then you throw taffeta into the mix à la Claude Montana. And then the models — Willy’s friends, Willy’s world, Willy’s own cultural common sense — projects a Miguel Adrover worldly whisper, which is a particularly interesting parallel as these shows are staged in New York, just like Adrover’s were. The big characteristics that constitute great twentieth century American designers, merges with fresh cultural ones. So those unmovable couture idealizations within the Geoffrey Beene woman, sync with Chavarria’s street couture, that Harlem-meets-Malcolm McLaren vibe, from Williwear — but for men.

‘I kind of see myself more as Willie Smith. I was so obsessed as a little boy. At the time, I thought about how his career worked. He was true to himself as he brought something new to the industry, and to retail. It was his world. He took a big chance and actually had a career.’

Yuji wears shirt and trousers WILLY CHAVARRIA Fall/Winter 2022.

Narrating real street styles is an ethnography, that requires minimal research for Willy Chavarria since he lived it. That importance stays with you. ‘My crew is very creative and very smart.’ Communicating authenticity to an audience that does not speak the language is made simple for Chavarria by working with friends: Karlo Steele, Marcus Correa and Carlos Nazario. They help the fashion public find a way into understanding what is happening. ‘I’ve known Karlo for years,’ he recalls. ‘We met in New Orleans when I lived there. I was happy to work with him because we aligned on the same point of view as very close friends. Marcus Correa was a protégé who worked on the barbershop show (Fall/Winter 2022, Spring/Summer 2023) and now Carlos for Fall 2023 into next season. It's important that I work with people who easily get it. Then you can just get on with the bottom-line message of each collection.’

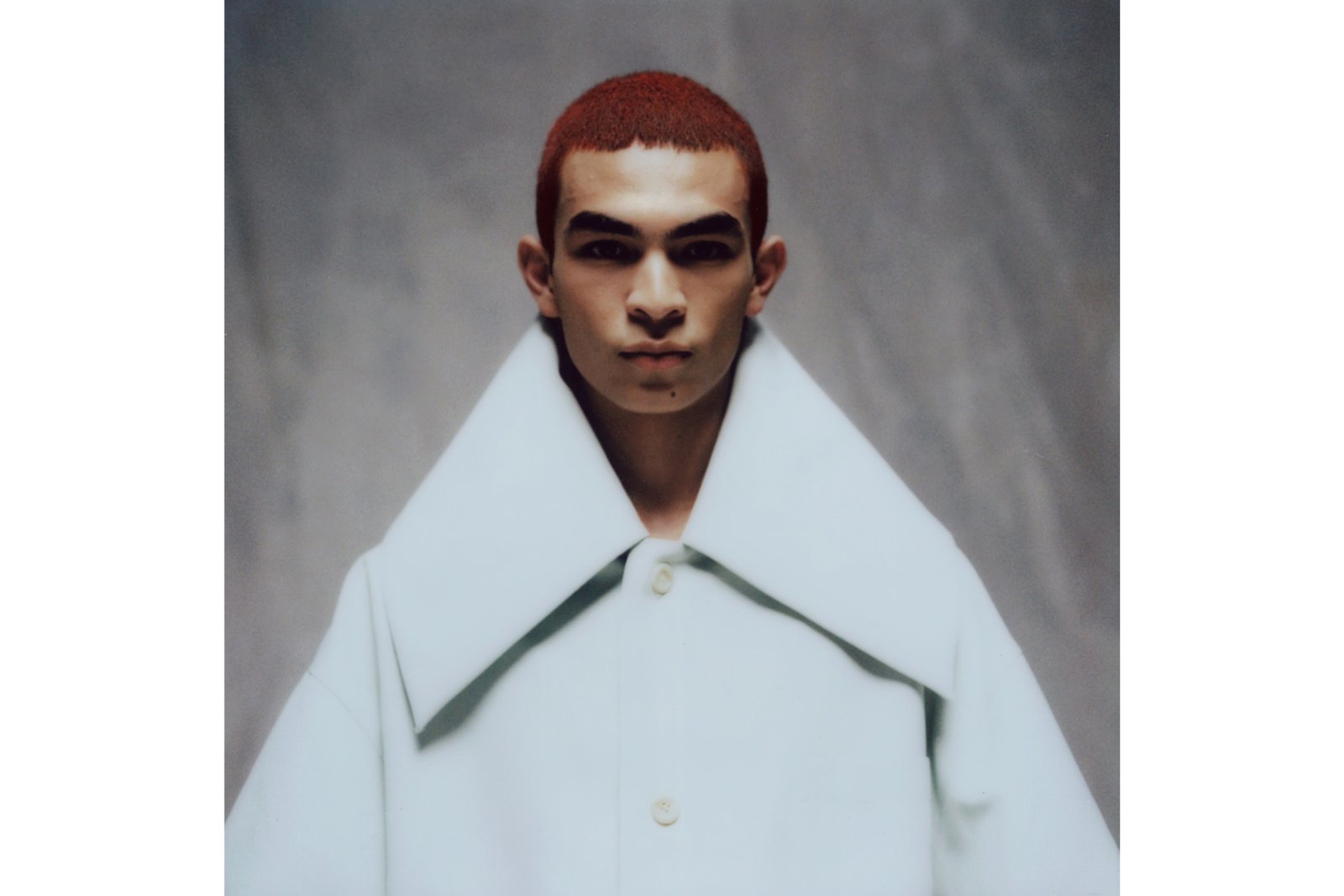

Keizo wears top WILLY CHAVARRIA Spring/Summer 2022.

Willy Chavarria fashion shows routinely dodge spot-on understandings like clever entendres utilized in Cruising (Spring/Summer 2018) and Love Garage (Spring/Summer 2020). Cruising proposed signposts, dualities really, with newsboy caps representing both Peter Lindebergh supermodels (fashion) and Tom of Finland-style BDSM leather daddies (genuine gay articles). ‘Through my entire life and through so many Brown, Chicano people's lives, it is prohibited to have those things intermixed. So actually, I was a little bit scared about that show,’ he says. ‘Then you walk into the Eagle and it’s like roses everywhere. So it’s a double entendre again. We had guys burning frankincense. And then the song! The song was Smokey Robinson singing ‘Baby let’s cruise…’ For Spring/Summer 2020, Chavarria fearlessly staged ‘Love Garage,’ a shameless celebration of ribald queerness through joy from 90s house music. Campy machismo from ‘hardcore’ barrio boys in the film I Like It Like That, presents a way to understand ‘Love Garage.’ When Timberlands and tank tops, tattoos and gold chains define the criteria set for being a ‘real’ man, that absurd mindset spirals into camp hilarity, not far removed from Nathan Lane’s shrieks in The Birdcage. If that was too scholastic, just think of Grace Jones, stylish sex workers and those boys whose sexiness shines because they are unaware of it. Except when they are, which is what made ‘Love Garage’ such a vital Chavarria moment. That and 12-inch records from Big Beat. ‘That moment in time really inspired me, how I create and how I love fashion. I just wanted it to feel like that moment — house music at its sexiest in the club. Then we come together in this moment where we are feeling ourselves at our most extreme levels.’

Lina wears jacket WILLY CHAVARRIA Spring/Summer 2023. Tights FALKE. Shoes stylist's own.

‘That is why I surround myself with Brown, Black and Queer people. That is why my team is made-up of all three … The story, the bigger picture that we create, is not just me, it is everyone involved.’

Brown and Black; reclaiming and legacy; sophistication and street; kindness and cocks. Each extreme is a branded code that hones Willy Chavarria’s focus in the tightrope negotiation of remaining true to yourself. ‘That is why I surround myself with Brown, Black and queer people. That is why my team is made-up of all three. It's because we all know this. We all know that we're the ones that build something great and show that off to the world. The story, the bigger picture that we create, is not just me, it is everyone involved and then the people tell the story in real life.’

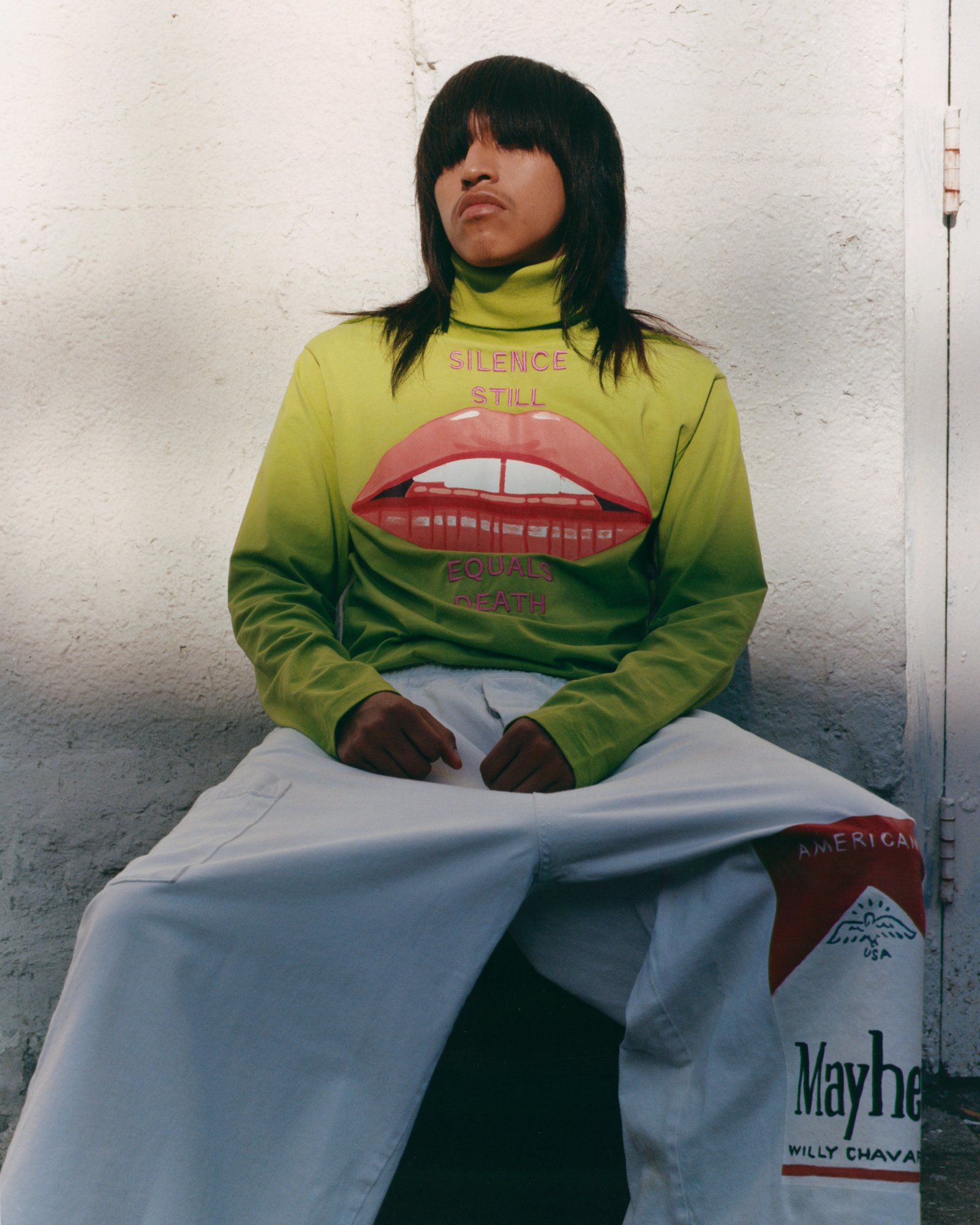

Yuji wears shirt and trousers WILLY CHAVARRIA Spring/Summer 2018.

Multiple meanings from the WC’s body of work explain life inside and outside of designer clothes, that his brand of sincerity is neither simple nor sublime. It is a hard-fought heaven sat beside a daily, living hell. ‘Marco Castro always does my makeup. In ‘Love Garage’ the makeup was cuts and bruises. Glam always has to include grit. It's good to have both. The beauty in the fight makes us all so strong.’