In Conversation: Nathanael Cox & Dominique Petit-Frère

This story appears in Justsmile Issue 3, Reflections are Protections.

Photography Bryce Thomas

Text Diallo Simon-Ponte

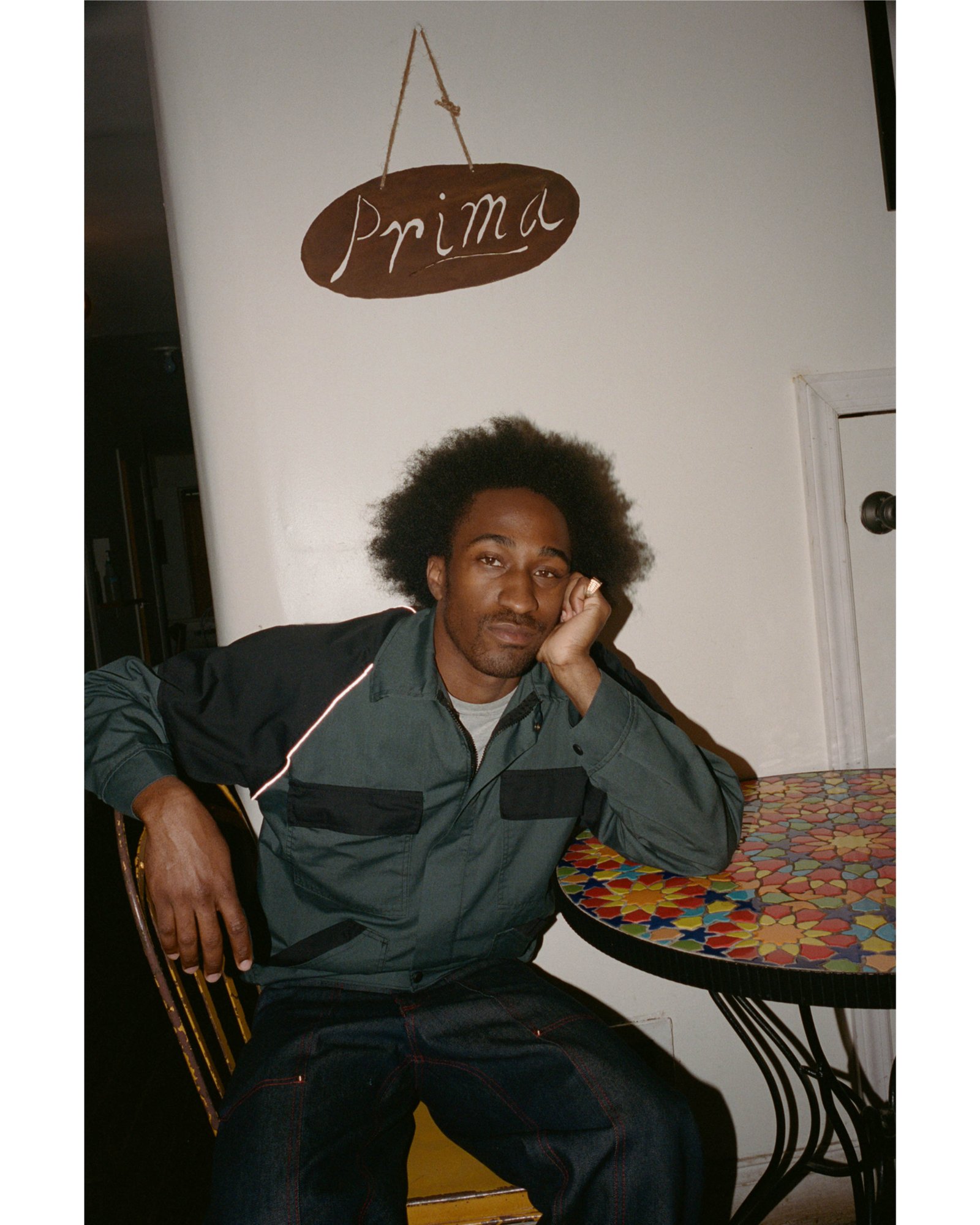

Nathanael Cox, photographed at Prima in Brooklyn, New York.

Crossing Washington Ave, I stop and queue ‘Wise One’ by the John Coltrane Quartet – the chords are an appropriate accompaniment for what I’m about to walk into. The melodramatic saxophone riff is interrupted by a young woman who falls into step alongside me. ‘Do you know of any good places to eat around here?’ she asks. Smiling, I nod, ‘I’m actually on my way to see a chef.’

Shortly after, I’m watching Brooklyn-based chef, Nathanael Cox work the floor at Prima Brooklyn – a restaurant nestled between brownstones in Clinton Hill. The stage from where he performs is delineated by a red brick wall that spans the entire left side of the establishment, spilling into a visible open kitchen. My mind dances with possibilities as the chef hunches over a large bin of something out of view. I’ve pored over the menu; it’s intricate and nostalgic.

Saltfish fritters w/ crème fraiche and horseradish. Marinated shrimp w/ yellow yam and burnt sugar. Oysters w/ fresh coconut milk and lime and Pear tart with cardamom whipped cream and rosemary.

Nathanael's process photographed by Lucia Bell-Epstein.

I’m sat near the door, with a direct eyeline into the kitchen, trying to study his deportment in a way that will not disturb. Nate’s shoulders pinch and his arms poise surgically as he carefully strings together his melodic polyphony of flavors. It’s my nose that hears the song first. It smells like Caribbean aunties laughing over the stove on a Sunday afternoon. The intensity with which he executes his task means he won't notice me. His hands move with rigor, while his face remains serene. A large overhead stove vent looms above his figure. He pivots from his work to reach for a shelf where his personal assortment of spices rests, sidestepping his sous chef, he returns to his original position with the growing confidence of a chef easing into his fourth week at Prima. He catches my gaze. ‘You hungry?’ he tosses out, his words thickly coated with a lifetime of Caribbean household nourishment. With the Escovitch mushrooms pickled in white wine vinegar that I had immediately ordered upon entry, still playing tricks across my tongue, I nodded to let him know, indeed I was.

A little over a year ago, I came upon Nate’s menus and began venturing out to his self-coined ‘Big Chune’ food pop-ups. Through flavors and cartographic gestures, he harnesses a socio-historical culinary synesthesia where oysters flirt with tamarind mignonette and Trinidadian roti with pomegranate seeds. A gastronomic intersection of the diaspora, Njideka Akunyili Crosby-esque, colors and histories float in and out of the foreground. Very slowly, I chewed on a few of the plantain chips lying at the top of the menu at Prima, and overcome with youthful delight, licked the residue that remained on my fingertips. Images of childhood moments flickered along, whispering, ‘Tell me, where do you remember me from?' I strained and focused desperately, fighting towards a promised land of legibility. Ah yes, I nodded once more in conclusion – mango and garlic powder, spices that enact reminiscence of meals cooked by tender mothers and loving elders.

Recipe by Nathanael Cox

Here at the table, history is positioned a little closer to the palate. The seventh item on this menu is, bammy w/ mussels and clams, chicories and fresh coconut milk. Bammy is a cassava flatbread – the origins of which stem back to the indigenous Arawak natives – Jamaica’s original inhabitants. Traditionally made with toxic bitter cassava, the centuries-old procedure involves peeling and finely grating the root, squeezing it to eliminate any excess moisture and then shaping the dry cassava into pucks before cooking the molded root vegetable. With my plate clean and belly full, the true purpose of his practice dawns on me, continuing to feed my spirit well past the meal. Cox’s cuisine investigates notions of luxury in the fine dining space, an archival presentation of recipes, posturing the strength of a meal as education.

Considering this reorientation of the old, into new fluid narratives reminded me of the first time I met architect Dominique Petit-Frère. Standing outside of a Moses Sumney, opening at Nicola Vassel on 10th Ave between West 18th and West 19th Street, she was looking up – there is much to stare up at. The Haitian-Ghanaian architect was in town, presenting her architectural studio Limbo Accra to The World Around Summit at the Guggenheim (2022) – the ethos of which is rooted in the experimentation of aesthetic and culturally significant unfinished, decayed concrete structures in West African cities.

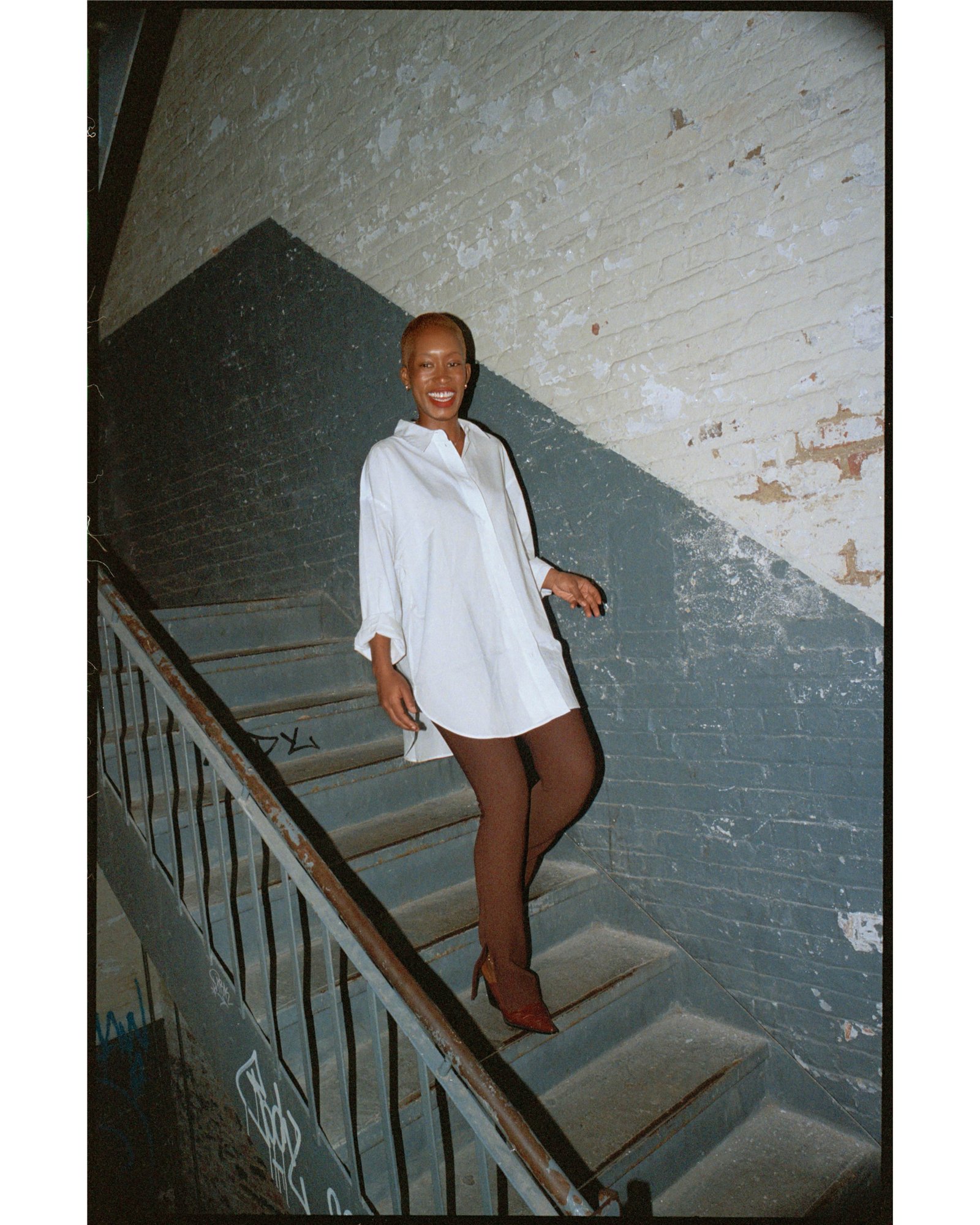

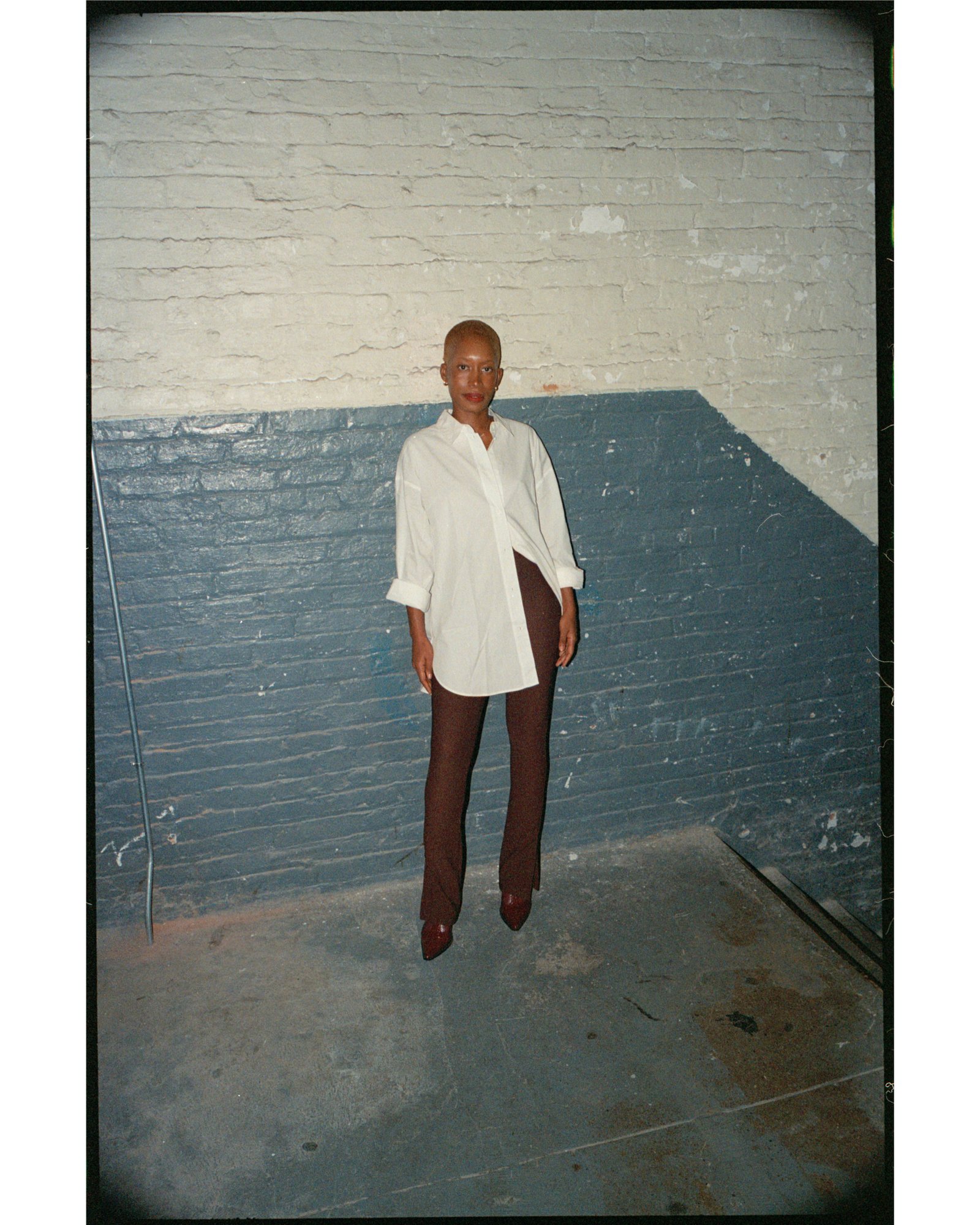

Dominique Petite-Frère photographed in Brooklyn, New York.

In 2018, while conducting her master’s thesis in Ghana, Petit-Frère began to take note of the plethora of uncompleted buildings – ‘concrete skeletons,’ she calls them – that scattered the city of Accra. ‘Oftentimes people fail to complete their buildings. Either falling short of money, the land not being suitable to build or the government coming to sack you whatever the case may be,’ she says. ‘I live in the city of Accra where a third of every building is incomplete.’

Through exploring the relationship between community and what its existing architectural framework may promise for the future, Limbo Accra – in partnership with Virgil Abloh, Daily Paper, Surf Ghana and more – designed an afro-utopic skatepark in the city. Utilizing the current skeletal infrastructure, the land was not raised, but rather reused and adapted to serve Ghana’s burgeoning youth skate community. On site stands a café, skate shop, gallery, several open areas and surrounding shrubbery. What was reborn here expands beyond the realm of skating, intentionally so. Blossoming from between the cracks in the concrete are the spatial parameters for social change.

Interior rendering of 'Engraved' by Anne-Lise Agossa, copyright Limbo Accra.

‘Charging older buildings with new intentions gives me a sense of meaning, a sense of power. You don’t necessarily need to be an architect to build.’ – Dominique Petit-Frère

From the rubble, Petit-Frère is determined to re-purpose the decisions of past generations to accommodate the needs of the next. ‘There’s such a beautiful and creative industry in Accra, that I sought to push these structures as a site of public space and activate them through art installations, performances or talks,’ the architect explains. ‘That’s what I’ve been on the pursuit of from 2018 until now. Charging these older buildings with new intentions, gives me a sense of meaning, a sense of power. You don’t necessarily need to be an architect to build.’

It’s clear that both Cox and Petit-Frère use their individual work as an exploration of their temporal sense of the immediate, while constantly tugging on historical threads of the past. Both of their practices encompass a respect for what came before it, while remaining conscious of the responsibility to preserve and uphold.

To explore these foundations further, Cox was tasked with devising a historical, narrative-based recipe, while Petit-Frère was asked to design a restaurant, home or room to hold the dish – incorporating its ingredients into the architectural aesthetics of the space. Here, they appear in conversation to discuss their spiritual practice of research and reflect on their respective offerings.

Interior rendering of 'Engraved' by Anne-Lise Agossa, copyright Limbo Accra.

Diallo Simon-Ponte: Nate, in reading over the footnotes accompanying your recipes, there are clear references to Jamaican and Ethiopian cuisine. Can you take me on a trip along your line of thinking there?

Nathanael Cox: Dominique mentioned taking inspiration from Ethiopian churches. There is an important cultural connection between Ethiopia and Jamaica through Rastafari and Ital diets. I decided to make Ital dishes. Both recipes are imagined to be served together. It is a culinary adaptation of Ethiopian shiro wat. There is a back and forth between the recipes from Jamaica to Ethiopia to Jamaica and then back to Ethiopia. The Ital diet itself was influenced by indentured servants from India which is something that is also a part of Jamaica’s history. Ital food is a post-slavery thing.

DSP: Dominique, the renderings you’ve put together here are incredibly unique, but also terrestrially evocative of the Rock-Hewn Churches of Lalibela.

Dominique Petite-Frère: In the first conversation I had with Nathanael, there were many key elements that I was drawn and attracted to. Particularly certain food products that are shared across the African diaspora and the key experience of him not wanting to work within a traditional kitchen and dining space and how that is conveyed through the products he harvests and uses for his ingredients. Combining that unconventional non-Eurocentric perspective to the space was something I was called to. Even the church symbolism as well, which came in the later part of our initial conversation – where Nate proposed that alternative spaces of consideration could be churches, since in Jamaica they have so many. So here in the renderings, we also have the question of what a church looks like within a Black spatial practice, particularly in Ethiopia. Piecing those discovery points that we arrived at in our conversation is where I wrapped my head around the design.

Dominique Petite-Frère photographed in Brooklyn, New York.

‘There’s a suggestion of resistance ingrained in the cuisine because of the cultural lineage that it belongs to. Growing a particular food so it can keep you alive is a form of resistance.’ – Nathanael Cox

DSP: Going back to that first conversation you both had, Nate after discussing the food of your upbringings Dominique exclaimed: ‘We are both here because of the yam.’ Did that play a part in your thinking about the recipe you conceived?

NC: Yam really in quotes. Yam is the potato or any of these starches or root vegetables that keep people alive. Even the squash. In this dish, Kabocha squash is a provision that is treated just like a yam pretty much. Kabocha traditionally is used in soups and stews.

DSP: The footnotes of your recipe also mention Rastafarianism.

NC: One of its main concerns is the liberation of Black people, so there’s the suggestion of resistance ingrained in the cuisine because of the cultural lineage that it belongs to. Growing this particular food so it can keep you alive is a form of resistance.

Like the same ingredient Kabocha is one of the main ingredients in soup joumou from Haiti where Dominique is from. Soup joumou is the soup Haitians eat on Independence Day because the enslaved couldn’t eat it. The soup was only reserved for colonial masters and plantation owners. So, using Kabocha in the makeup of an Ital dish is this layering of suggestions of resistance.

Nathanael Cox, photographed at Big Chune in Brooklyn, New York.

DSP: Dominique, there is a tree in the center of one of the designs that is labeled as a tamarind tree. Why did you choose to include that?

DPF: Putting a tamarind tree in the middle of the restaurant symbolizes a utilitarian purpose. It provides shading and operates as a source of life. You can harvest from it. My hope for the tree is that it will outlive the generations that planted it and continue on after. It is rooted and takes this idea of rootedness. It is also inspired by Nathanael and how rooted he is as a culinary artist. I was harping on multiple notions of rooting.

DSP: In previous conversations we’ve had you let me know that collaboration is a large part of your architectural practice. How did that play out in this project?

DPF: Working on this project, I was in collaboration with an architect that I work very closely with. Her name is Anne-Lise Agossa. That’s one thing I like to carry out within my practice: the idea of a collaborative studio. Engaging in dialogue and gaining perspectives from younger African architects, is a space that I don’t feel is platformed enough. Anne-Lise and I were both able to collaborate in terms of the modeling, the renderings and so forth.

DSP: What spoke to you about the word ‘Engraved,’ as you chose a name for the restaurant?

DPF: I named the restaurant ‘Engraved’ as I was thinking about the etymology of the word. It means something that is etched in, carved in. When we think of our shared cultures and our shared histories from Africa, throughout the diaspora it has been carved in and it has been engraved to some extent.