In Conversation: Ja’Tovia Gary and Immanuel Wilkins

This story appears in Justsmile Issue 3, Reflections are Protections.

Photography Bryce Thomas

Text Daria Simone Harper

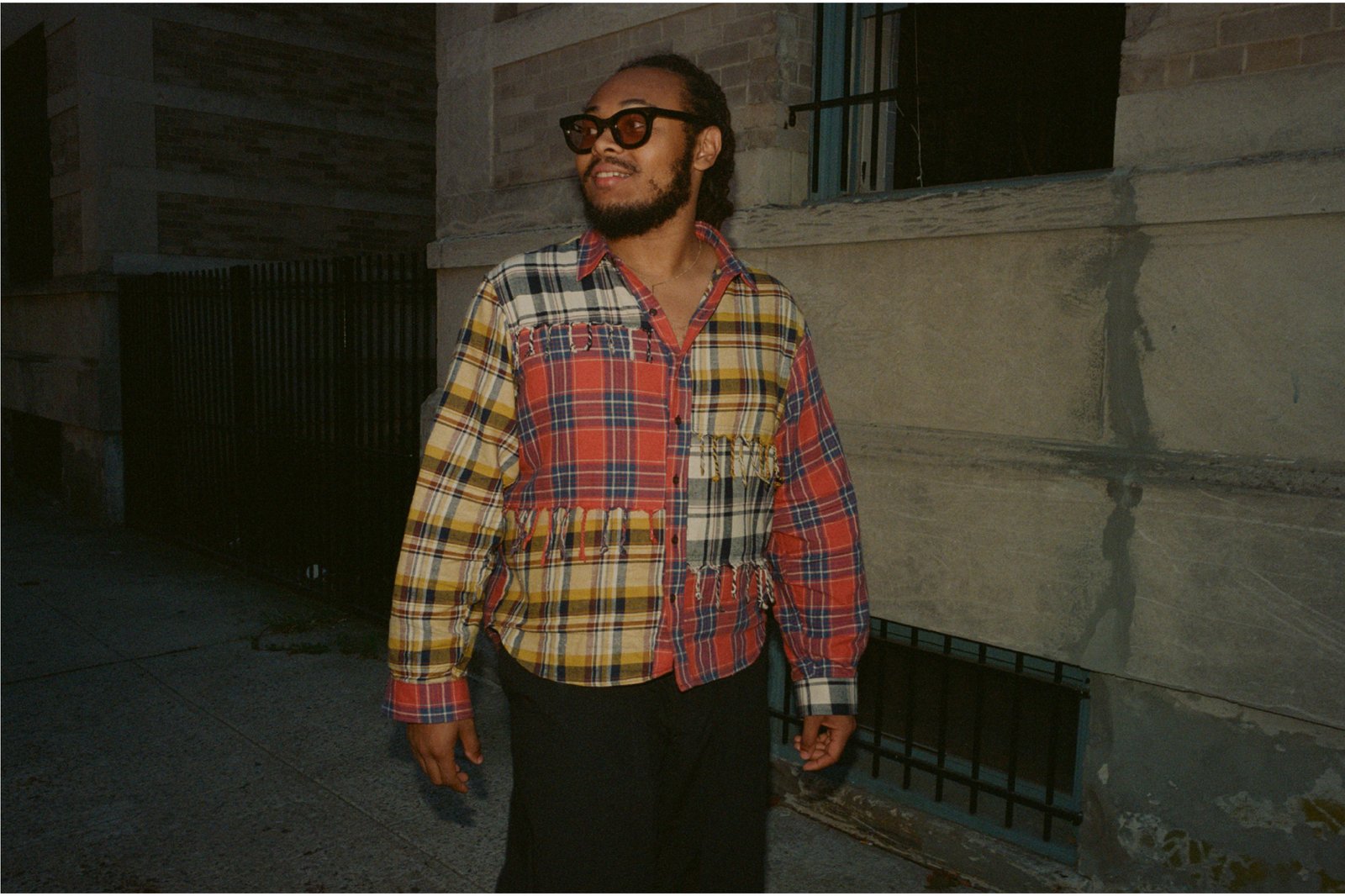

Immanuel Wilkins photographed in Brooklyn, New York.

Situated along the shadowy floor of Paris’s galerie frank elbaz, a series of points form the base of a pyramidal structure. An anchored foundation expands upward to a floating precipice, reflecting the monumental stature of the form. From the surface of its broad cushioned walls, sprout bunches of cotton balls interspersed with dried flowers – a projected video floats and whirls across the fixture’s exterior. Fragments of archival footage show individuals, many of them women and girls, walking through nature, laboring or playing. Layered amidst these fluctuating scenes are flashes of fervent animation in vibrant reds, pinks and blues. Dancing across the richly textured object, the resulting film traces and engages with notions of Black feminist tradition and scholarship, matrilineal legacies and states of liminality.

This sculptural installation, architected by filmmaker and interdisciplinary artist Ja’Tovia Gary, absorbs all who enter it – igniting an ecstasy as aural and visual frequencies converge. As the Dallas-born and -based artist describes, it is both a womb and a portal. Gary possesses a distinct artistic vernacular, often centering themes of ancestral knowledge, memory and archival resources through a lens of Black feminist subjectivity.

The sculptures in Gary’s ‘Citational Ethics’ series (2020-23) highlight the intellectual contributions of Black women writers, scholars and thinkers, transferring their words into physical forms made of neon, metal and other materials. Meanwhile, films such as Quiet As It's Kept, 2023 and The Giverny Suite, 2019 subvert dominant narratives surrounding Black women’s bodies, probing histories which force these bodies to become spaces of labor and commodified production.

Ja'Tovia Gary photographed in Brooklyn, New York.

The present work, as you yield her your body and soul was presented in ‘partus/chorus’, a group show Gary curated at the French gallery in early 2022. The presentation centered around the legal doctrine established during the period of chattel slavery in the United States, this doctrine translates to ‘that which is born follows the womb,’ and held that a child’s status as slave was dictated by the mother’s status. Launching from these thematic points of departure, Gary reifies the Black womb as a site of limitless possibility – of transfiguration, of inception and of destruction and ‘a portal by which historically subjects have become objects,’ as described in the exhibition text.

The sonic arrangements of saxophonist and composer Immanuel Wilkins reflect a parallel interrogation of portals and liminal spaces. The Brooklyn-based, Philadelphia-raised jazz musician, who experienced Gary’s aforementioned artwork while traveling in Paris, follows in a tradition of artists whose role as energy workers must not be overlooked. Throughout Wilkins’s sophomore album, ‘The 7th Hand’, the artist and his quartet explore what he has described as ‘relationships between presence and nothingness.'

Over the course of an hour-long suite comprising seven movements, Wilkins and his bandmates shift from performing written music, to eventually improvising. In the progression toward this free jazz state, each movement performs a revelatory role, as the musicians embody the divine. Each section of music – whether played with spirited vibrance, or slow and sustained – is filled with bursts of frenetic energy. The notes flying forth from each instrument initiate a meditative listening experience, reminiscent of those conjured by jazz legends such as John Coltrane or Phaorah Sanders.

Both Gary and Wilkins are bestowed with a sacred ability to shape fields of energy and the environments in which this energy exists. Each artist’s decision to orient aspects of their respective artistic practices, around notions of vesselhood, points to a larger query of what is at stake in becoming a conduit of the divine.

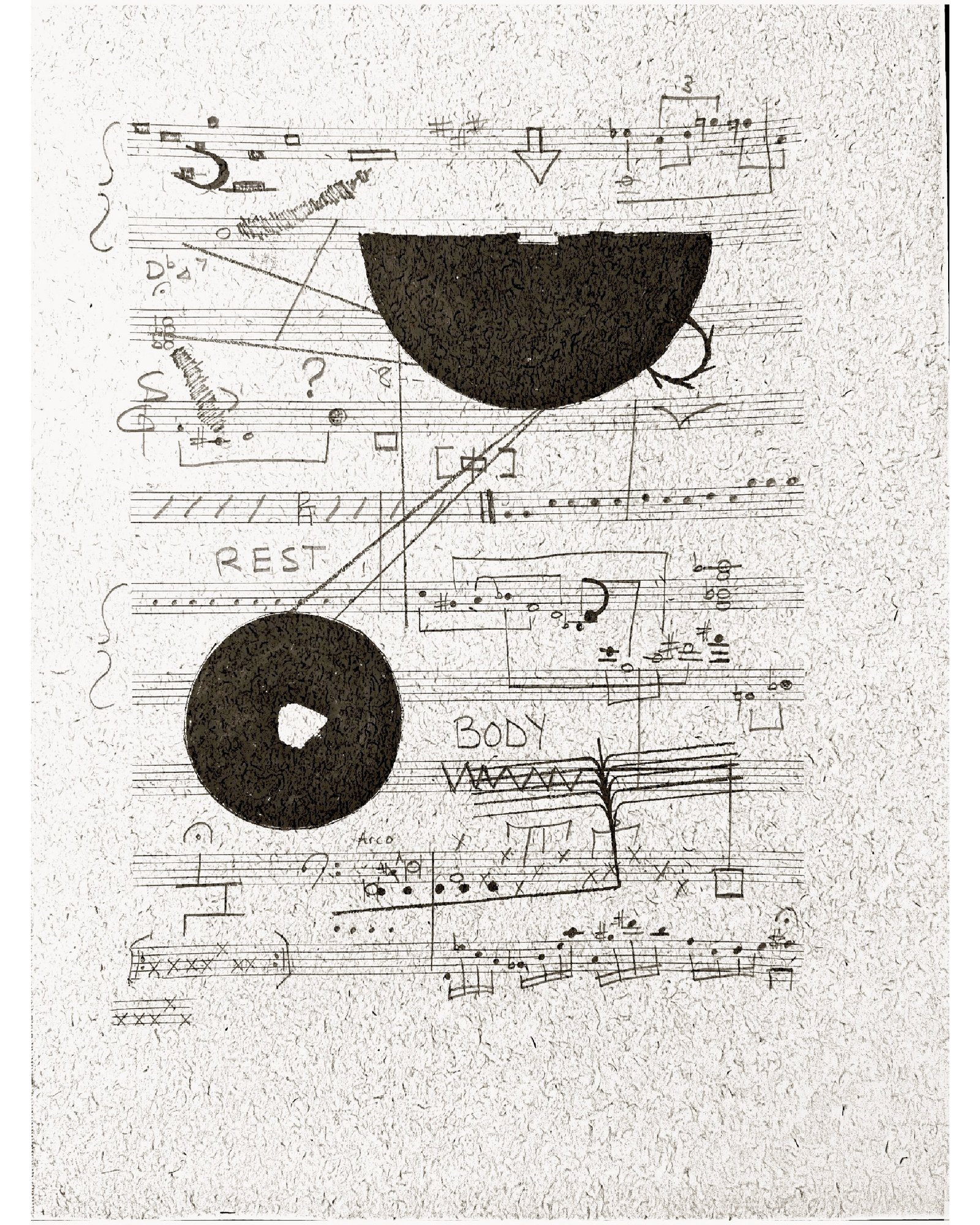

Handwritten and annotated sheet music by Immanuel Wilkins in response to Ja'tovia Gary's installation, as you yield her your body and soul, 2022.

Daria Harper: You shared that you met in 2019 during Theaster Gates’ Black Artists Retreat. Can you describe the memory of experiencing one another’s work for the first time and what drew you to it?

Ja'Tovia Gary: For me, it wasn't in a public setting, I was at home listening to Immanuel’s music and thinking: ‘Oh, okay, this is a musician musician. This is somebody who really plays music.’ I wouldn't say I'm a jazz head, but I probably listen to a lot more jazz than someone my age and it's usually folks from the past. I don't know a ton about contemporary jazz.

Listening to Immanuel's work was kind of shocking, but also affirming, because there's an ongoing tradition of young people who are very much working in the tradition of those who came before them. The fact that this jazz aesthetic is alive and well is very exciting to me.

Immanuel Wilkins: I was introduced to Ja’Tovia’s work at the Black Artists Retreat. I believe they showed The Giverny Suite…

JG: They may have shown Giverny I, which is a very short version of The Giverny Suite. They probably also showed An Ecstatic Experience, which opens with Alice Coltrane and has this whole moment showing Ruby D with these animations around her.

IW: Yes! After that, I obsessed over your work for a good two months. I was fascinated with the direct animation. One thing that’s shared between my compositional practice and the way you create your work, is that it’s really durational and often takes a long time. I'm okay with having a slow, methodical process in order to make something that I love.

JG: Yes, you're confident in it because you know how long it took and you know how long you tarried over each note. There are elements of my practice that are very fast, but slow and steady does indeed win the race. You have to fall deeply in love and be deeply obsessed with the process.

‘Both the structure and the materials that are being projected are coming together to tell this story around the history of Black women’s labor and the spiritual work that we have done to push things forward.’ – Ja’Tovia Gary

DH: Speaking of the process, Ja’Tovia, I’d love to talk about your recent installation as you yield her body and soul. I’m interested in the way you're thinking about the Black womb as a site of transformation, as a site of creation and destruction, but also as a portal. Can you talk about your process and some of the thematic elements that shape the work, including your use of materials and footage?

JG: This whole period of my life feels so deeply transformational. I've been thinking a lot about liminal spaces … in-between spaces or thresholds. Moving from one existence or one reality to the next, and how that in between space is its own thing. That's why I thought about creating this kind of spaceship mothership portal. I wanted you to go inside of that space and think about what a transformative experience might feel like.

To me, the materials are really important because I'm always thinking about the very specific reality of Black women, Black femmes, Black queer folks and the labor that comes with creating that portal for everyone. Black women's wombs have been this kind of vessel for commodified production, for commodified goods.

I was thinking through history's grip on us and our bodies, but also considering our metaphysical contributions. If anyone is going to usher us to the other side, it might be somebody that looks like me. So, I drew from my own family experiences and my own familial archival pieces. There's a montage that's being projected onto the surface of the structure. It really centers and celebrates the women in my family. You see my great-grandmother Sarah, my grandmother, my great aunt. My mother as a little girl, me as a little girl. Both the structure and the materials that are being projected are coming together to tell this story around the history of Black women’s labor and the spiritual work that we have done to push things forward.

Immanuel Wilkins photographed in Brooklyn, New York.

DH: Earlier you mentioned the way that music and sound play into many of your films. How does sound work as a tool for you in this installation?

JG: The music is always super important and it often structures the piece. Even before I shoot, or before I edit, there's usually a playlist that I've got, or there's a song that I've written down. My work has non-traditional, nonlinear, experimental structure and usually it's the music that I'm pulling the structure from.

For the sound piece in the installation, I have to shout out my collaborator, Nelson Bandela AKA Norvis Junior. He’s a producer and we've collaborated a few times, we’re actually both from Texas. I hit him up and gave him this song by the great gospel singer LaShun Pace-Rhodes, may she rest in peace. It's her version of a song called ‘Is Your All on the Altar?’ at first, we had the whole chorus on it, but it was too long and I just wanted a sustained moment. We took one note, the word ‘soul’ and we stretched it out and lowered the pitch. We made it the main component you hear when you step inside the space. That's what gives it that emotionality.

IW: That's literally what I felt experiencing it. I hit Ja’Tovia up as soon as I left the show, thinking about this audio component. It’s almost like you’re pressing pause. You’re in this in-between, kind of non-temporal space where time does not exist. Everything is slowed down.

Ja'tovia Gary, as you yield her your body and soul, 2022.

DH: Immanuel, you’ve also been thinking about the act of being a vessel or a channel. When speaking about your latest album, ‘The 7th Hand’ – you’ve described this idea of being a ‘conduit for the music as a higher power’ that actually influences what you and your bandmates play. What’s the significance for you of interrogating this sort of liminality, in this deeply spiritual way in the act of playing music?

IW: When I set out to write the music, I actually took about two years away. Writing the piece felt like a daunting task. The idea of a suite of seven pieces that would turn the musicians into vessels by the seventh movement felt like such a crazy thing to even put on myself. It felt like it was too sacred for me to touch. To say, ‘Yeah, I can conjure this up.’

The first six movements are pretty much all written music. The improvisatory sections get longer as you go on. A lot of the sixth movement is improvised and then the seventh movement, there's no material.

‘I wanted the music, in and of itself, to carry the energy and bring us to the place we need to be. We start levitating, ascending.’ – Immanuel Wilkins

DH: How does the seventh movement shift from performance to performance with the changing energy of you and your bandmates?

IW: It's vastly different every night. I've only really talked about that last movement once with the band, and we were ruminating on the idea of what our waiting room is. What I mean by that is … when nothing is actively happening, what is the stasis area of sound? What does our waiting room sound like?

Earlier Ja’Tovia mentioned this idea of tarrying over a note, and actually in the Pentecostal church, they have tarry services where you just sit and wait on the Holy Spirit. That was something that I kind of appropriated to the band.

Finding that sonic familiarity allowed us to start in the same place every night, and go different places from there. I wanted the music, in and of itself, to carry the energy and bring us to the place we need to be. It's a personal thing between the four of us on the stage. We start levitating, ascending.

‘There's this affirmation that I say to myself, and it ends with, “I do not get lost in the waves. I ride them. I float, I play, and most sacredly, I enjoy it.”’ – Ja’Tovia Gary

DH: Can you both explain why it’s important to you to explore these ideas of liminality and vesselhood throughout your practice?

JG: What's been driving a lot of my thought processes and conceptions behind the work is not only the idea and concept of change, but the inevitability of it. There's this affirmation that I say to myself, and it ends with, ‘I do not get lost in the waves. I ride them. I float, I play and most sacredly, I enjoy it.’

This idea of the portal and the threshold was my attempt to prepare myself to go forward in this next stage in my life. There's always going to be shifts in life. The older I get, the more comfortable and welcoming I am to those shifts – even if they are distressing at first or perhaps fear and anxiety inducing.

IW: There's something that I feel at home about knowing that we're steadily moving and everything happens on a spectrum. That's been my strong suit, really living in the gray area. I've always thought about it as a part of my practice. We're constantly in flux.