Curator and artist Justen LeRoy is making space for conversation and sound

Made in partnership with Burberry. This story originally appears in Justsmile Issue 2, Together in the Fold.

Photography Barrington Darius

Styling Tamia Mathis

Text Jonathan Jayasinghe

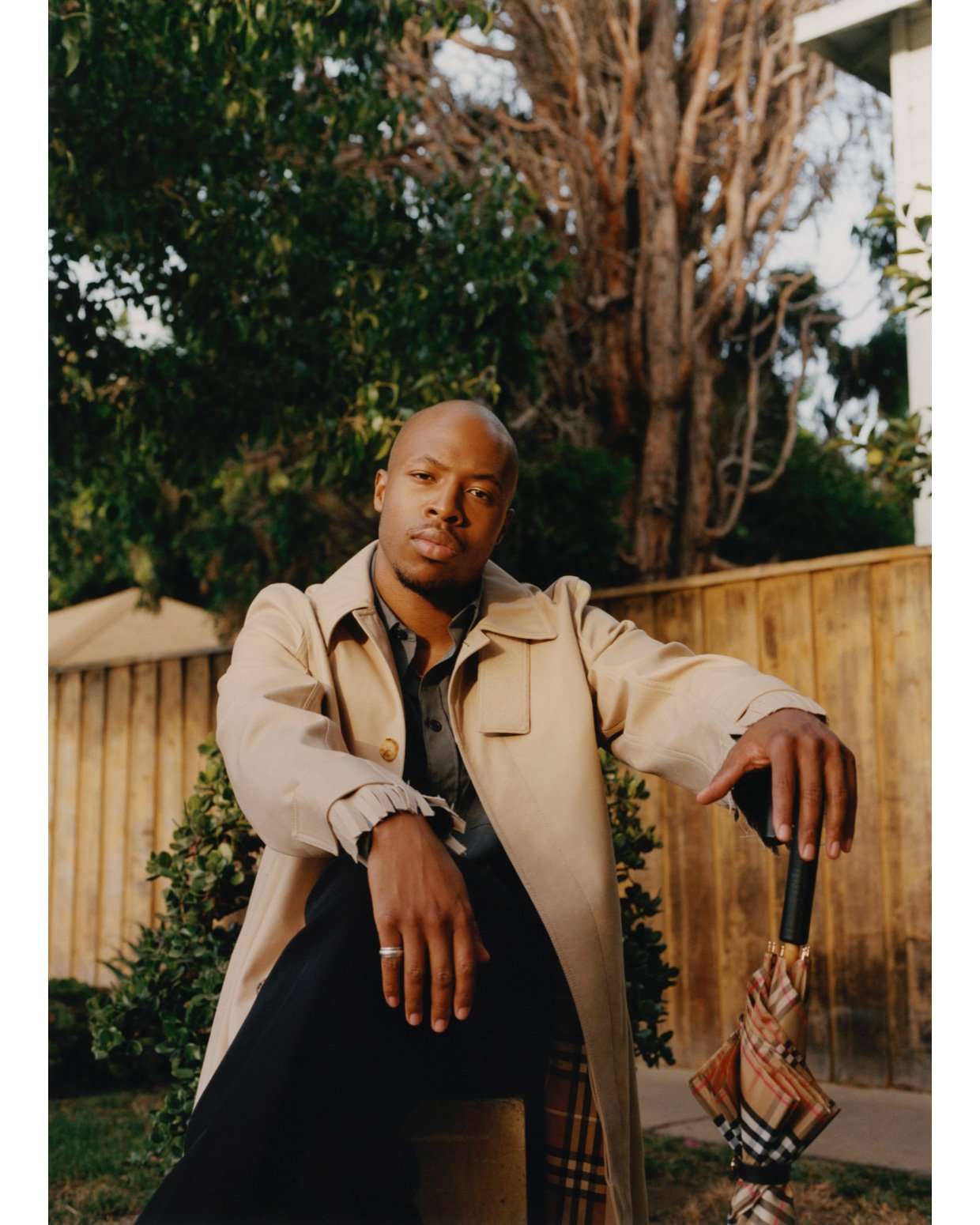

Justen wears coat, shirt, trousers and umbrella BURBERRY.

The South Central, L.A. raised creative is an understatedly prolific figure within Los Angeles’ cultural and artistic landscape. After a hot as hell summer, we talked to Justen about being an independent curator for Hammer’s Made in L.A. biennial, how his platform SON. is taking on its own shape, and making music with his father singing over voice memos from friends.

One of the first things you notice about the curator and sound artist Justen LeRoy is an extraordinary warmth. Even over an audio-only Zoom call, through the chilling filter of laptop speakers, his voice carries the geniality, mindfulness and care, that’s enabled him to become such a distinctive and prolific figure within Los Angeles’ cultural and artistic landscape.

As a multidisciplinary artist and creative, Justen’s work spans multitudes. He’s the founder of SON. – a platform dedicated to exploring the multidimensional experience of Black life through sound, curatorial and programmatic work, with its base of operations in Justen’s father’s long-standing barbershop. He’s an influential voice and collaborator within one of the city’s most vital cultural institutions, The Underground Museum. He’s created and performed music with the likes of Klein, Slauson Malone and Xzavier Stone. But across the varied media, forms and spaces in which his work manifests, there’s a consistent approach and point of view. The approach is community-driven, accessibility-focused and guided by a commitment to creating intimate spaces for conversation.

I had the pleasure of catching up with Justen on a quiet Sunday afternoon for a conversation that covered a range of topics, including sound, space and the elusive nature of Black pleasure.

Jonathan Jayasinghe: How’s your summer been?

Justen LeRoy: My summer’s been hot as hell. In the spring, work was back-to-back. But this summer has allowed me some time to really dream again and think about what I want to do next, and who I’m speaking to or who I’m making work for. And that reflection has led me to the conclusion that I can do whatever the fuck I want to do.

JJ: That idea can be freeing, but also a bit daunting.

JL: 100 per cent. That realization has been a blessing and a privilege, but I also choose to be mindful that whatever I do is making space for someone else and that it’s moving things forward.

JJ: Where’s that realization leading you right now?

JL: I think that in the work that I’ve had the privilege to do so far, it’s been about making space for conversation. But now that I’ve had that experience, I’m looking for ways to make space for sound. Sound has been my main thing, and I’ve been working to expand on that since my contribution to Hammer’s Made in L.A. biennial. I’ve been thinking about how I can take up entire spaces with sound.

I’ve really been on my Fred Moten shit, and have had some great conversations with him about sounds; moans, screams, cries. And also, the idea of melisma, with runs and riffs. These are all wordless notions that we can recognize within Blackness. There’s a certain tone and recognition, and I’m looking for ways to create more space for that. I’m trying to create space for those types of expression that don’t necessarily require language as much as feeling.

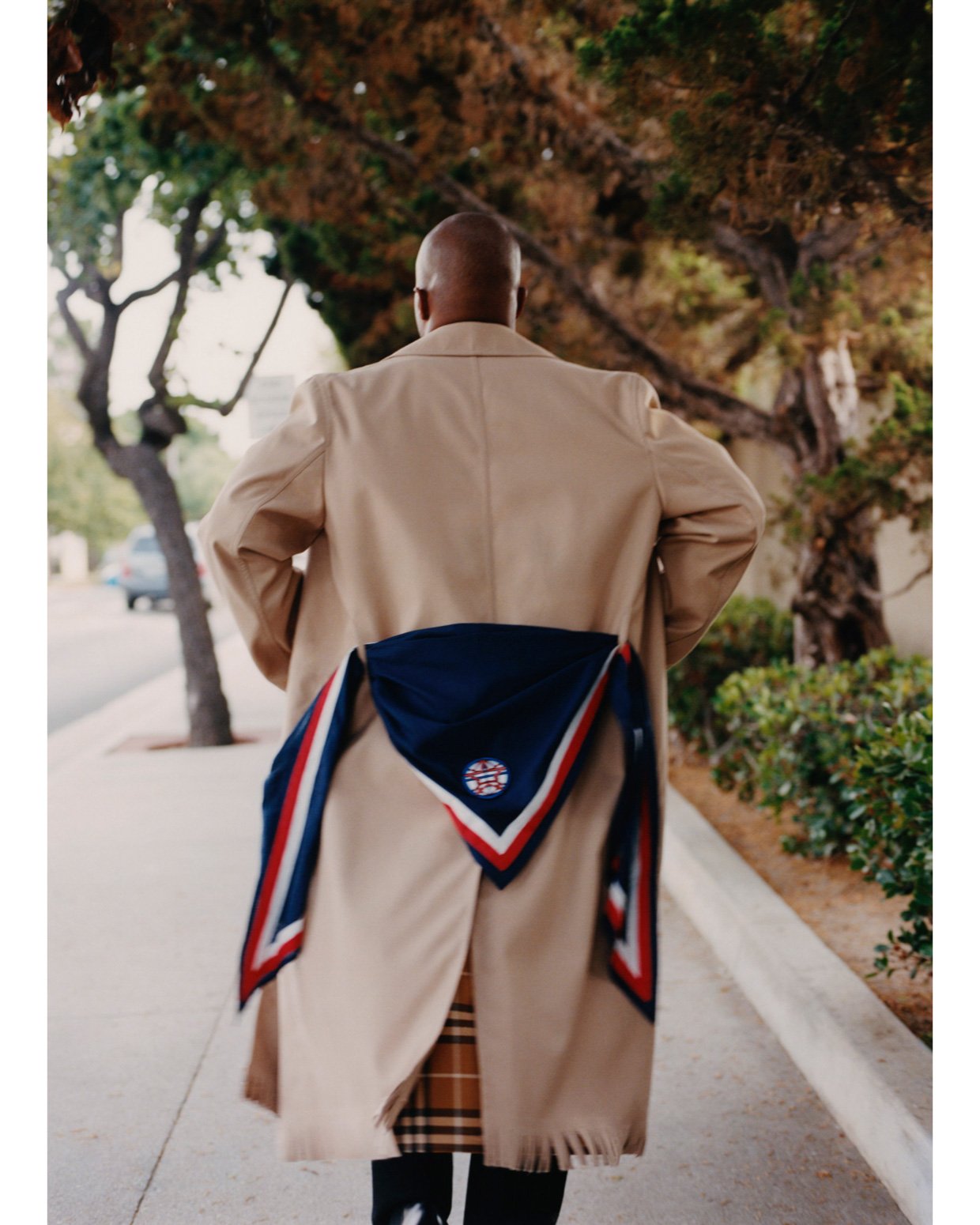

Justen wears coat and scarf BURBERRY.

JJ: This idea comes to life quite vividly in the Leave A Message (2020) project that you did for Made in L.A. What was the inspiration and process behind that work?

JL: When the curatorial process for the exhibition began, the curators, Myriam [Ben Salah] and Lauren [Mackler] reached out to me to see what I was up to. At the time, I was only focused on transforming my dad’s barbershop into an incubator space, to talk about art and culture. And I think that they sat with my vision for that. They came back five months later after hearing some of the NTS broadcast that I had done and essentially asked me to create another version of that.

What was beautiful about this project was that it gave me a home for things I’d been working on that I didn’t have a home for yet. The first part of the piece that you hear, I’ve had that for over a year. It’s my father singing over voice memos from friends. And then I had a friend of mine, VCR, come through and she laid down some violin. From there, I just kept on adding pieces and reached out to people to share phrases, sentences, expressions of gratitude, anything. It was important to me to make something that felt intimate, in a time where we really couldn’t be intimate.

I was also thinking about the lost art of the voicemail. How people used to come home and hit play on their voicemail system, and unwind from the day while listening to the things that people wanted to express to them. I thought it would be special to create something that felt warm, like you’re in your home and taking in the stories and sentiments that people wanted to share with you.

JJ: Having seen the breadth of work included in this year’s Made in L.A. exhibition, much of the work that I found most striking was the work by Black artists, and a lot of that work was adapting to the conditions and themes of a post-pandemic world. That adaptability is endemic to Blackness, as a cultural sensibility and aesthetic form. We often find ways to thrive in even the most unlikely or impossible circumstances. Is that something that you think about in regard to the work?

JL: That’s kind of all I think about. I think there is something magical that happens when we’re pressed up against the wall. I’m not always proud of that resilience or the fact that we have to be that way. But I do feel like that’s what gave birth to this project. Initially, I was going to do a podcast and have people meet me at my father’s barbershop and have public talks that engaged folks from the shop. But with everything getting locked down, we had to adapt and it helped give shape to what the project is now, which I think is even stronger than what it would have been otherwise.

JJ: SON. was founded in 2016 and has since evolved into a variety of different forms. How would you characterize its evolution over the years?

JL: At this particular moment, I would characterize it as a feeling of surrendering. I think I initially had a really specific idea of what I wanted SON. to be, but it’s taken on its own shape and journey that I think is beyond me. It’s taken me to places that I never would have imagined. Initially I was like ‘SON. needs to have this, it needs to be that,’ but now I’m just like, it just needs to be, it needs to do what it wanna do.’

I’ve learned a lot through what SON. has shown me. There are moments where I don’t want to be the ‘SON. guy’ and I want to focus on music or this and that. But the possibilities and opportunities that keep showing up are aligned with the world I want to see. SON. has a farther reach and deeper resonance than I might have on my own.

“My dad used to be Brandy’s bodyguard, and every Friday we would go to the set of Moesha on Sunset and Gower. My interest in process evolved from being on that set ... it was a very L.A. set, it felt like Leimert Park, like a cookout – I learned what a Black creative space could really be.”

JJ: Shifting gears a bit, how has growing up in L.A. and South Central specifically, informed your work and your practice?

JL: I think that L.A. gave me a good entry point into what I love, namely: Black people. A lot of people that visit have this misconception that there’s no Black people in L.A., but I was surrounded by Blackness, growing up. Also, I always knew that I loved singing and music, but for a lot of my life I didn’t have access to the arts.

Despite that, I did have some interesting points of entry into the world of art. My dad used to be Brandy’s bodyguard, and every Friday we would go to the set of Moesha on Sunset and Gower. My interest in process evolved from being on that set, and seeing how work gets made in a collaborative environment. That experience let me know that I had access to that world. I think because of that experience – and it was a very L.A. set, it felt like Leimert Park, like a cookout – I learned what a Black creative space could really be.

Then when I was in college, I got into Tumblr – things like [Kimberly Drew’s] ‘Black Contemporary Art’. I started to feel like I could have a voice and career in this world and I started to pursue it. The Underground Museum was all of those experiences coming full circle for me. And this is where the community piece comes in, enabling me to bridge these different things in this city.

JJ: One of the most exciting parts of this year’s Made in L.A. biennial was the citywide installation of Kahlil Joseph’s BLKNWS (2019) newscast. Could you tell us about that work and the role that you played within it?

JL: When we were preparing for Made in L.A. I was brought on as a project manager and independent curator, to think through where we could program BLKNWS throughout the city. I wanted to prioritize places where we don’t always get access to art or this type of conversation. There’s some in Compton, there’s one at Hank’s Mini Market on Florence and Crenshaw, St. John’s Hospital, Cedars- Sinai Hospital, my dad’s barbershop, Sole Folks in Leimert Park, and on and on from there. I felt that BLKNWS could heighten the conversation in those places and vice-versa. Because there’s so much richness in the city and I just wanted to slip BLKNWS in to see how it might set things off in different contexts.

It’s always amazing to me how BLKNWS will put the familiar next to the unfamiliar, and start whole new conversations. And I’m able to take these conversations that I hear in those spaces back to the editing room and share with the team there, and those reactions often influence the work as it continues to evolve.

Justen wears coat, shirt, trousers and umbrella BURBERRY. Ring Justen’s own.

JJ: The level of conversation and cultural critique in everyday Black spaces is often so much more sophisticated than institutions or the broader culture will recognize.

JL: I definitely think that the level of conversation and insight that I see in everyday life is way more compelling than what you might see in any given art institution. What people are talking about every day in South Central is the most exciting shit to me. So, I try to find ways for us to factor that into the work. And it’s been a really great experience to see BLKNWS exist outside of the white cube, in everyday spaces, and create a new idea of what contemporary art can be and who it can reach.

JJ: On a slightly tangential note, something that I’ve been thinking about a lot in the past year has been the idea of Black pleasure versus Black joy. Does that dichotomy resonate with you, either personally or in your work?

JL: It’s what I was talking about earlier with sound and the melisma. I get so much pleasure out of hearing someone do a beautiful riff or a run with a certain type of tone or rasp. And I don’t think that’s something that can be experienced if you haven’t lived a Black experience. I think non-Black people can acknowledge it, study it and celebrate it, but I think there is a singular pleasure that we’re able to experience that others cannot. It’s very specific to us.

Also, I don’t think that Black pleasure can be packaged in the same way as Black joy. And I’m glad for that. Like a photo of a Black child smiling can become the face of a white-owned, Black-servicing hair- care company. But I think it’s these other things that they haven’t figured out how to commodify yet.

JJ: That makes me think of the clip in BLKNWS, of the three dudes watching Whitney Houston perform the national anthem at the Superbowl.

JL: Yeah! I think that Whitney piece is one of my favorite things that BLKNWS has done.

JJ: And it ties back to what we were saying about the level of critique, which can even be wordless sometimes. In that clip they’re yelling, they’re hugging and reacting to very specific nuances of her performance.

JL: I don’t think they understand specifically what it is about her performance that’s prompting that reaction, but it moves them deeply regardless. It’s like in church, when people are singing and you’re moved, and you might not even believe in Jesus or the Bible or anything, but the performance does something. It changes the space; it changes you physically. Something chemical happens, it makes your hair stand up. I’m so into the celebration of riffs and runs and the unique effects they can produce. I want to have a whole exhibition around just that.