Ignacio Gatica's Global Uncanny

The visionary Chilean artist talks capitalism, placelessness, and getting lost in the Camanchaca.

This story appears in Justsmile Issue 5, How Do We Belong?

Photography Raphaël Gaultier

Text Drew Zeiba

Ignacio Gatica in his Bushwick, New York-based studio.

The watch has stopped at 12:29. A yellow sun with curlicue rays rises beneath the unmoving hands. A simple metal armature clamps the watch to a concrete plinth engraved with text derived from declassified US documents of interventions and subterfuge in Latin America. This watch, a political campaign souvenir, joined eight others whose faces displayed maps, symbols, and even politicians’ portraits in New York–based, Chile-born artist Ignacio Gatica’s installation Terce at SculptureCenter in 2022. The installation—with its fixation and freezing of time and its poetics of history—distills Gatica’s interests in mediating the visibility of political economy’s mechanisms. We see the watch’s functioning not because its gears are exposed (they aren’t), but because it no longer ticks.

In 1996, French philosopher Jean Baudrillard contrasted the clock counting down to the new millennium in Paris’s Beaubourg Center to the national debt billboard counting interminably up over Times Square. Nobody bothered to look at the dwindling Beaubourg clock, he wrote, but the national debt with its multiplying figures drew enthusiastic attention: “Americans are so eager to advertise their domestic debt in such a spectacular manner,” he sneered. The ’90s debt billboard’s peak would’ve been quaint by today’s estimated nearly $36 trillion. Even if the US’s financial and military hegemony were to collapse, it’s hard to imagine anyone would get repaid, since the number exceeded fiscal reality—or, in Baudrillard’s estimation, accrues in a “parallel reality.”

Ignacio Gatica peers through a magnifying glass.

Other nations don’t have such luck—including the many countries of the Global South forced into coercive loans with entities like the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund. For the people of these countries, debt manifests in a reality of austerity maintained through state and corporate violence—a reality not parallel nor even coextensive with another, but merely reality as such. This systematic and constitutive inequality of neoliberal capitalism animates Gatica’s work. For Sujeto Cuantificado, a solo exhibition at Von Ammon Co in DC, Gatica displayed scrolling LED screens showing financial metrics and found poetry alongside credit card readers, and other devices and images exploring finance and urban space. In Stones Above Diamonds at the Hessel Museum, narrow shelves cradled credit cards, printed with Santiago façades boarded up during 2019–20 protests, that, when swiped, disrupted a stock ticker ring overhead with messages appropriated from graffiti tags. In the photo series Fantasmas, elegant images reveal emptied luxury storefronts still aglow.

But Gatica does not emerge as an “amanuensis of capital,” as theorist McKenzie Wark describes would-be critics enamored of financializaiton’s glossy horror. His work is too polysemic and mysterious for that. Gatica draws us into the absurdity and sublimity of this asymmetric globe of speed and excess, tempting us with its perverse beauty. In this communion we receive not revelation but inchoate dreams of the possible: of our power to turn our never-knowing into another world. We receive the hope of poetry.

Drew Zeiba: To me, your art navigates a very complex relationship between representation and abstraction. That is, you’re often “representing” things that are in-themselves abstractions. Money being the most extreme example. But also corporate logos or stock symbols. Neoliberal capitalism uses abstraction in very insidious and violent ways, laundering its abstractions’ material effects through further abstract terms. But poetic or artistic abstraction is often one of our best tools to think and do otherwise. What’s the push and pull of abstraction like in your practice?

Ignacio Gatica: What I’m realizing now more and more is that those abstractions stem from policies that are recent to our life experience and they transform material spaces into more abstract or ambiguous ones. If we start thinking of, for example, external debt, which I’ve been fascinated by in the past few years, all of those numbers are just abstractions too. It’s really hard to relate to them because of their quantitative nature. How do you translate them into something we can grasp, something that’s within our life experience?

DZ: Even a number that’s accounting for something “real” can become useless to describing reality in human terms. I can’t relate to a billion or trillion, no matter how concrete of a thing it might be describing.

IG: Exactly. Their being abstract is telling. Organizations like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund create these ciphers, but then what we receive from that is maybe intentionally hard to grasp. It’s kind of like going to a rave, and then going out of the rave. Perceiving the rave is hard—the smoke, the lights, the drugs we take, everything makes it an abstract experience. It’s hard to have a memory. You are left with an experience of feelings and colors. That’s like living in New York. The business and information is constant. I am looking into that after-rave experience and asking, “What is there?”

Of course, in my practice, I often link it to the history of Santiago, where I grew up. But I try to bring it into the realm of poetic abstraction rather than make “political art.” I like the excess of meaning. I think some people who have written about my work really get the political dimension because they try to historicize it and they need to in order to create a story. But I think there is a more kaleidoscopic part of the work that people haven’t really described yet.

DZ: With your photos of the storefronts or your bright moving-light installations, I’m so drawn to them. They not only show objects of desire—luxury goods or growing wealth—but also, as aesthetic objects, evoke desire in me as a viewer. I’m wondering about desire or other affects that you aim to work with in the sculptures and installations.

IG: That's exactly how I think about it when I’m making an object. I have to be desiring to do it, but also, that’s often where the attention comes from, too. Even in this photo [from the Fantasmas series] I’m looking at right now, it’s a very similar experience to being a window shopper: of being someone who is looking through glass at an object of desire. The difference is that in this photograph, the object isn’t there. The stores were empty.

DZ: You took these during the covid lockdown, right?

Glitches are real life too... I think urban space globally has lost its human specificity. The Dior storefront in New York versus the Dior storefront in Chile—they look the same.

IG: Yeah, and because they were afraid of looting or who knows what the products weren’t there. This was also an important historical moment of asking what kind of agency we have in civic space. And for me, there was also something beautiful about having the mental space of seeing an empty store. It was very alluring.

DZ: The empty stores are kind of surreal. It’s almost as if you’re seeing a glitch.

IG: Glitches are real life, too. We’re not always aware, but it’s nice when we have that realization.

DZ: The glitch is also maybe an intervention into frictionless speed. So much of your work is about circulation, flow, and the directionality of power. You’re talking about capital moving across the globe and military-backed political-economic ideologies that move from DC to South America. But as you’re dealing with these historical and contemporary systems, you’re also relating to these places in more immediate ways, whether through appropriating local political campaign paraphernalia or reproducing graffiti. As your work speaks to and from different parts of the Americas—and is soon being shown in the US, Chile, and Argentina—how do you move through these different but simultaneous aspects of place and placelessness?

IG: I think urban space globally has lost its human specificity. The Dior storefront in New York versus the Dior storefront in Chile—they look the same. The glass buildings of New York are imitated in Santiago even though the climate conditions are totally different. In Santiago we have a financial district we call Sanhattan. Urban space has changed placeness in terms of how it makes meaning, but still there are specific contexts that shape these, and that is super interesting to me. People have almost religious interactions with stores, brands, buildings, and that affects the human experience and the urban experience. It comes back again to that break. That dizziness. I wake up here and I have the same sensation I had there. I wake up here and have that sensation I had in that other place because they’ve both lost some dimension of their placeness. It’s tied to politics, it’s tied to history, and it’s tied to economics, but that’s in some ways the hardest to grasp because the language economists use is very abstract for everyone, even for them. A lot of decisions might be made by algorithms, but it’s also very emotional. As much as it’s abstract, selling and buying stocks is emotional.

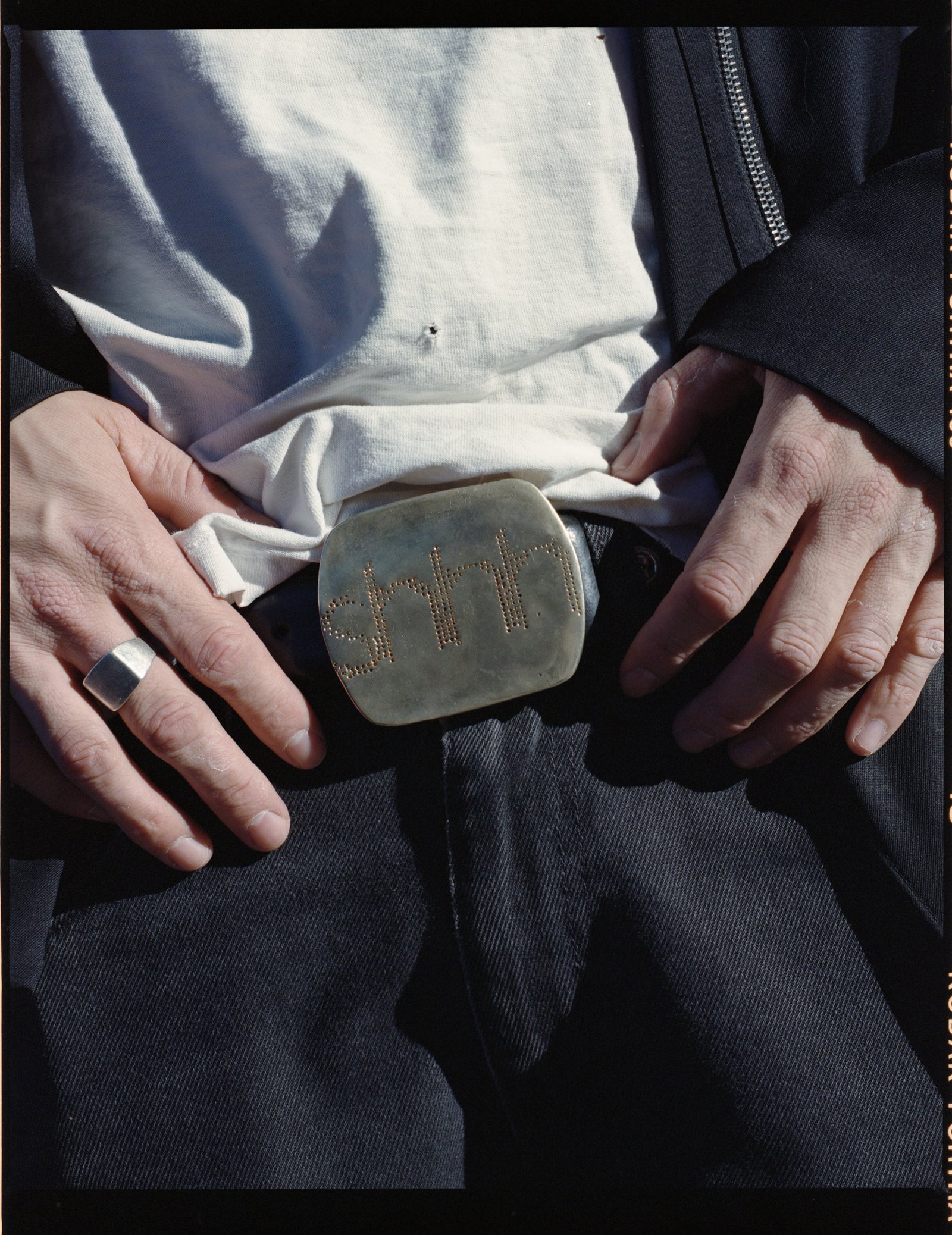

A detail from Gatica's installation, reflecting on the invisible systems that govern everyday life.

DZ: Talking about Sanhattan and places and placelessness, I wanted to ask about how where your work is being shown influences the work, if it does?

IG: I always try to take in consideration where I’m showing. But it’s interesting because now that you ask me, I realize I’ve been showing more in North America than in the rest of the Americas. But next year I have more stuff in South America, so I will see what happens. It still comes from very personal experience. These will be solo shows, which is a moment for me to translate the work in other conversations, rather than in a group show. I just had a group show in Mexico.

DZ: What were you exhibiting in Mexico?

IG: I showed a small ticker display with the external debt of the United States and of Mexico. [Preface to an Automated Stratosphere USA MEXICO] started with information from the World Bank, then an algorithm called SARIMA that’s used to predict stocks in the New York Stock Exchange. It’s making an abstract calculation of external debt. It’s almost a hallucination. [In other projects] I use an API, but the World Bank doesn’t have one. They only give you the external debt from each country from two years or so. It’s a power thing: they have the information; it’s not public. I used an algorithm, so it’s a speculation. Like the speculation of finance bros: they speculate on what to buy and sell.

I also exhibited a silver medal, because in Mexico they have a very strong history with silver. But instead of it showing the Virgin of Guadalupe, it showed Mexico City’s financial district, Centro Bursátil. It’s in an acrylic box like those used to display the hair of saints or something, with velvet inside. It has a religious aspect. I’m getting more religious. Brands also now have the specific religious aspect of believing in something abstract that’s given with a symbol rather than the actual object—like the Nike logo. Christianity has the cross. I think art is religious, too.

DZ: What’s pulling you toward religion?

IG: Maybe my family’s background, because they are all very Christian. My grandparents kind of raised me because my mother was very young, and she was working all the time, and I used to go with them to church every Sunday. And there’s a bunch of faith in art too. I think it comes back to that sensation of the unknown.

DZ: I feel like the unknown has a really funny resonance in a lot of your work. We’re talking about this algorithm that’s giving you information that seems super literal, but it’s actually speculative or hallucinated. But even if it were real it would be like, “What am I supposed to do with these numbers?” So much of what has to do with financialization has such a direct impact on how we live our lives, but its literal “information” or “knowledge” doesn’t describe that at all, or even really help you “know” the world. It feels Borgesian. Your work draws me into that temptation of “knowing” but then reveals that knowing’s ludicrousness. The limits of knowledge are a big part of the dynamism.

IG: Definitely, the limits of knowledge and the limits of systems of knowledge in comparison to the beauty of poetry that surpasses meaning.

DZ: Is this related to the idea of “emancipatory poetics” you’ve previously discussed? What does that mean for you?

IG: Being free and subverting machines. That’s what I like to do when I fuck with technology. It’s not that I like technology. I used to hate art that dealt with technology. But those things are part of our regular life, and they’re not transparent enough to notice them—or the transparency they do bring is not letting us see through. That’s where poetic emancipation as a concept comes in. It frees you from that state of not knowing and lets you appreciate the beauty of the moment. It’s something really mysterious too, but I think beauty is a state of mind rather than an appreciative part of reality. Poetry has the power to emancipate you from one mental state and bring you to another that’s a bit more beautiful. Of course it’s personal, everyone can deal with it in different ways. It can be through art work or reading or seeing something that happens in life. But I believe it’s rich enough to praise and to pray for. And you have to pray with the things you have around. Credit cards and stuff. I get that exotification that comes from the art world trying to find what’s rarest. It’s almost like the miners trying to find a mineral that’s pure. But that’s ridiculous, because that doesn’t relate to people. Everything is contaminated. Everything is contaminated by these things that we’re talking about. In the fall in the north of Chile where my family is from, there is this crazy, dense fog that’s called the camanchaca. It arrives in the desert and you can’t see through it. That’s where the mines are in Chile. For the miners, the scariest thing that can happen is getting lost in the camanchaca. You can get very screwed. You don’t know how long it is going to last. You don’t know if you have enough supplies. The weather really shows itself to you. Even with GPS, you don’t know where things begin and end. I don’t know what I was saying, I just got distracted by the camanchaca.

DZ: You got lost in the camanchaca. But—not to be too literal—there’s something about being lost in or disempowered by or in relation to these forces, entities, and systems that are beyond comprehension or of which our experience is one of experiencing their obscurity. It’s like how the ticker does or doesn’t visualize finance. How the watches and plinths do or don’t tell us time—do or don’t tell us about a specific moment. How the credit card reader as a video-art display makes us see consumption and commerce differently. So, being able to sense… Actually, this brings up something I wanted to ask about: What is your research process? And how does that research get distilled or realized in an object or an installation?

IG: I don’t have a methodology. I know other artists who do. Personally, I don’t make lists and then ask myself, “What’s the best idea?” or “What is more poetic?” No, it comes from a conversation, the news, a friend sometimes. I think it’s about desire and doing what you really want to do. That’s what keeps me making art.