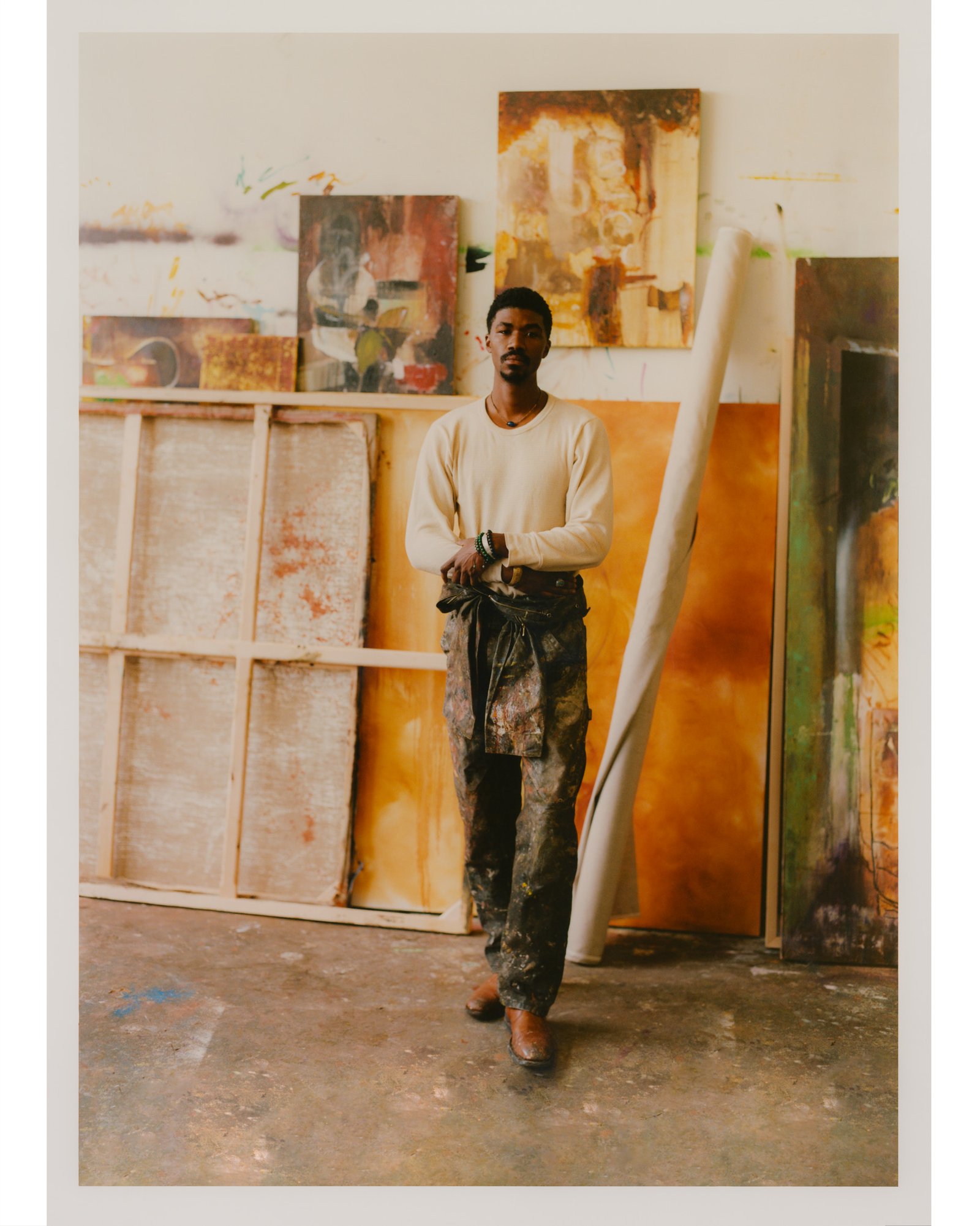

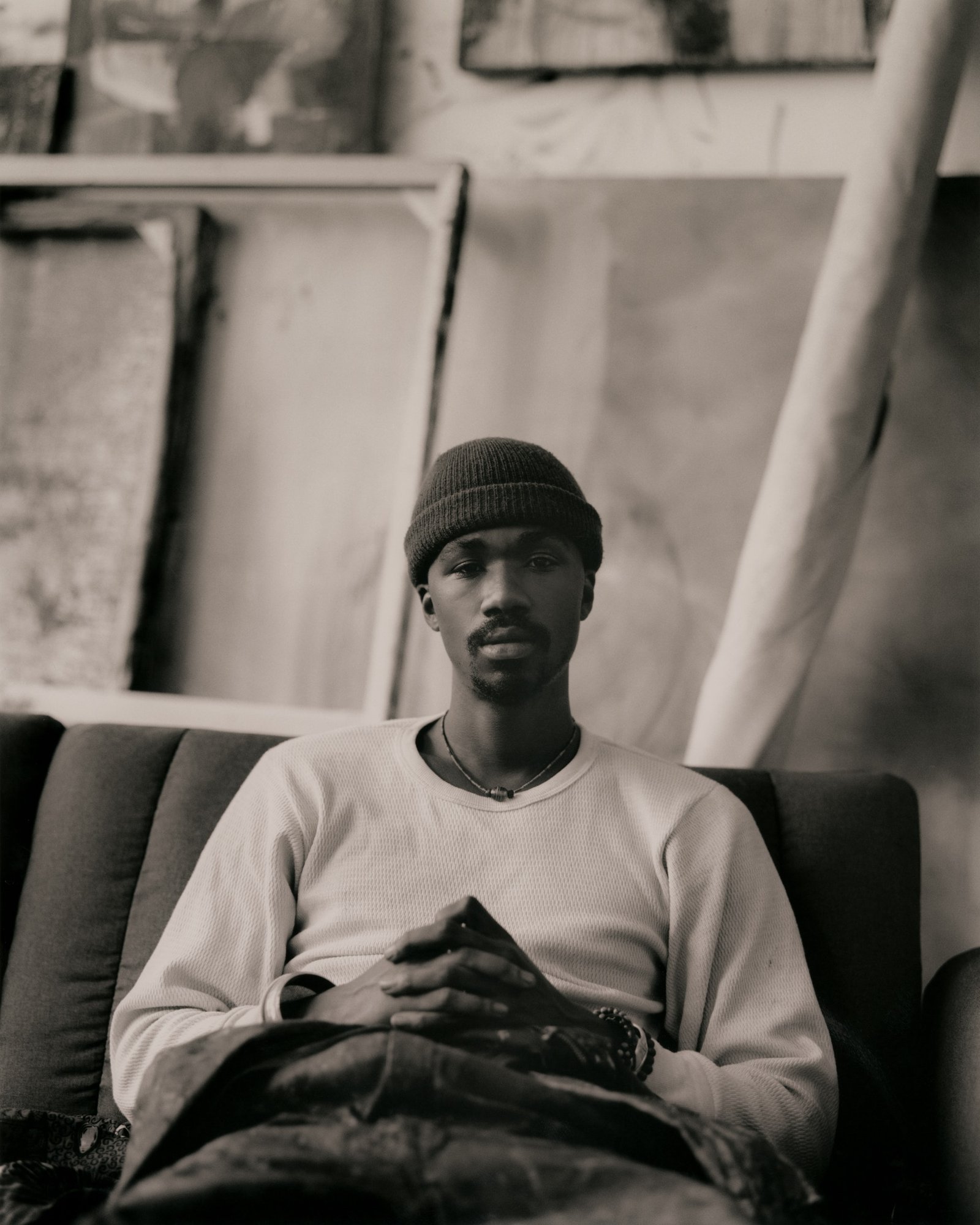

Devin B. Johnson paints the spaces in between material memories

The New York-based artist discusses his current solo exhibition, his journey as an artist, and finding beauty in the failure of memory.

Photography Kirtrell Morris

Text Jonathan Jayasinghe

Devin B. Johnson photographed at his studio in NYC

When visiting the artist Devin B. Johnson’s latest solo exhibition, My Heart Cries, I Set Out an Offering for You at Nicodim Gallery in Los Angeles, one is immediately drawn into the highly textured and enigmatic qualities of his latest work. Scenes of fleeting cityscapes, displaced and disembodied figures, and ineffable atmospheres are made tactile through rough yet luxuriant layers of paint on canvas. Made in the time following Johnson’s residency at Kehinde Wiley’s Black Rock, Senegal, the collective effect of the work in this exhibition is a rhythmic and absorbing exploration of the liminal qualities of memory and space.

A few days after visiting the exhibition, we connected with Johnson for a conversation via Zoom, in which we dug deeper into the memories and materials behind this new body of work.

How are you doing today? What’s this moment feeling like for you?

So you caught me on my second day back in the studio. I feel like a newborn zebra, getting my bearings and preparing myself for what’s coming up. Since the show has opened, I feel like the feedback I’ve been receiving is what I’ve been reaching for. I feel proud that the work has landed and that it’s being received in the way that it is. I think this moment and this body of work is the most complete snapshot of how I see myself, and my work, and is the most current iteration of my explorations to date.

How would you characterize that journey you’ve been on, and how it’s brought you to this current moment and these works?

At the beginning of the pandemic, I was in Senegal, at Kehinde Wiley’s Black Rock residency in Dakar. It was the first year of the residency, and I arrived right as the borders closed up. I was planning to be there for two months, and ended up there for four.

I’m the first one in my family to travel to the continent. I landed on March 1st, and my birthday was March 4th, so I experienced my 28th birthday there. The only time I was able to really experience Senegal before the lockdown was a trip that we took to Gorée Island, which is the island that many enslaved people passed through when being taken from Senegal to the new world.

That place was a point of no return for so many people, and then hundreds of years later, being the return that happened for myself and my family... It was a lot of emotion, I cried a lot. That was my first and last experience outside of the residency in Dakar.

By the time I was able to return to New York, I was seeing the remnants of the energy of the protests. Things like neighborhoods boarded up, but also the things that naturally occur in the city; graffiti, scrawling and writing on the walls, etc… It spoke to me of the way that memory naturally manifests in a city.

Tell me about your early development as an artist, and what brought you to the work that you do now.

I always had my colored pencils and construction paper, my crayola watercolor set. At a very young age I had a knack or an eye for colors. I remember the first painting I saw of a Black figure was a painting done by my uncle, who was the artist in my family. I grew up thinking that art was just a hobby, but didn’t realize all the places it could go or take you.

One time when I was in second grade we had a show and tell day. This kid, John, brought in a painting that I thought was so good, and better than the things that I was making. I was a little jealous (laughs), as an eight-year old. After that, I told my grandfather I wanted to take art classes, so he started taking me to a studio after school. There, the teacher had all these oils, pastels, chalk, and magazines and books to use as references, and I learned so much.

I continued to pursue it, and when I went to college, things really opened up. I wanted to try all kinds of things; sculpture, performance, painting, etc. But painting naturally became my strong suit.

“My current process is… navigating through the weird liminal spaces of what we’ve been experiencing over the past year.”

Your work and your process draw considerably from cities, and specific urban environments.

When I’m walking around the city, I’m taking in those messages that are coming from the landscape. I then try to articulate them haptically in the studio, in a tactile way. I’m interested in the way a facade or a wall has messages layered underneath, through graffiti, newsprint etc... My eyes are naturally drawn to the haptic qualities or haptic memories of the buildings, the subway stations, the sidewalks. My current process is really tethered to an understanding of that, and navigating through the weird liminal spaces of what we’ve been experiencing over the past year.

When I moved to New York, I wanted to make sure I was responding to where I was, geographically, in an intentional way. I wanted to respond to the landscape in a way that wasn’t necessarily placing my narrative into a place that I wasn’t from, but finding ways to articulate the way that the landscape was affecting me. I wanted to go into the studio and find ways for the paint to be applied sculpturally. That process led me to this group of paintings.

My experience viewing the work was that the paintings were less a depiction of a scene or a subject, and more of a perspective through which the viewer is invited to look.

The paintings operate in this way where I’m trying to manifest the fuzzy grey area of the subconscious. Carl Jung talks about how when the subconscious tries to form and reform its memories, and that the memories you recall are not the original memories themselves. They’ve been altered or contaminated or otherwise changed. There is a way in which the paintings have density, translucency, fuzz and figures or entities trying to come through to the surface, but not coming through clearly.

The pieces throughout the exhibition all feel like they’re in conversation with each other, but there’s a few pieces like Perch & Clutch, or Office & Save Two that render multiple perspectives of what feels like a single scene. Is this a new gesture or technique for you?

It’s kind of a new thing I’m trying to get after, and it’s related to music theory in the sense of repetition, and loops. It’s playing with the visual rhythm of different sized canvases next to each other, but all with the same subject matter rendered in different ways.

That’s interesting, the relation to music theory and creating visual rhythm. Does sound or music play a big role in your process?

When I’m here in the studio, I’m playing a lot of music and responding to it through my body, and dancing or moving in other ways to achieve the things I’m trying to explore. These canvases start on the wall, or on the floor, with me working over them, and so they’re very physical paintings in that way. Also I’ll sometimes collect leftover materials that I find around my studio, like photo paper from the studio down the hall. Sometimes I’ll use them as a drumstick, and beat paint onto the canvas, finding my own rhythm to discover an image.

It allows me to impose some of my own rhythm into the image, and can turn the canvas into an invigorating surface that draws the eye across it in a specific way. So I’m composing like a musician would, and playing on the canvas like a musician.

The subject of haptic memory is really compelling, in the realm of psychology but also as a concept applied in theory by people like Tina Campt, Laura Marks and others. Can you tell me more about how this idea functions in your work?

I’m reading this book that Kennedy Yanko recommended to me, by an architect named Juhani Pallasmaa. It’s called The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. That book is where I first came across the term. The idea is that our bodies have memories based on the objects or people we’ve come into contact with, or the spaces that we’ve inhabited. Which is why I find myself drawn to a nostalgic space. Haptic memory is what I see throughout the city and its architecture, and it’s that memory that I’m trying to express in these paintings. I’m still reading and learning about this concept, but I know now that architecture is something that I want to respond to and engage with.

It’s an idea that was growing in my sensibility for a while but I didn’t really have the language for until recently. Having encountered many artists who are great thinkers in addition to being great visual makers has made me want to get after my own artistic philosophy. Books about psychology and more recently, architecture have been helping me with developing that.

Have you read the Poetics of Space, by Gaston Bachelard?

That’s actually the next one I’m trying to get into. I’m really interested in semiotics.

One of the ideas he explores is this notion that when you grow up in, say, your childhood home, your perception of the space changes over time as you grow older, as you have different experiences in that space, etc. But when you’re older, and you maybe leave that space, it exists in your memory simultaneously as all of the different ways you ever perceived it.

That’s really good. That phenomena of conflating different experiences, that’s the fallacy of memory. It’s the overlaying of so many things that happened or could have been. So with the paintings and subject matter that I’m interested in, I’m looking at archive images or screenshots or photos I take while walking around the city, and I’m placing them in a digital space in Photoshop, to see what emerges and then trying to render those images through paint. It could enlist a response to my memory, but could also be indirectly speaking to it. Which is why I find it hard to go into my own photo albums and paint those things. It’s not about capturing memories, but expressing the failure of memory to capture moments.