How Brick founded Ebony Beach Club; the surf and arts collective

Founded with fellow Black surfers slash creatives, Gage M. Crismond and Tre’lan Tillman, Ebony Beach Club (aka Black Sand) is a collective-cum-safe-space, set on correcting the false narrative that surfing is only for white people.

Made in partnership with Burberry. This story originally appears in Justsmile Issue 2, Together in the Fold.

Photography Barrington Darius

Styling Tamia Mathis

Text Dominic Cadogan

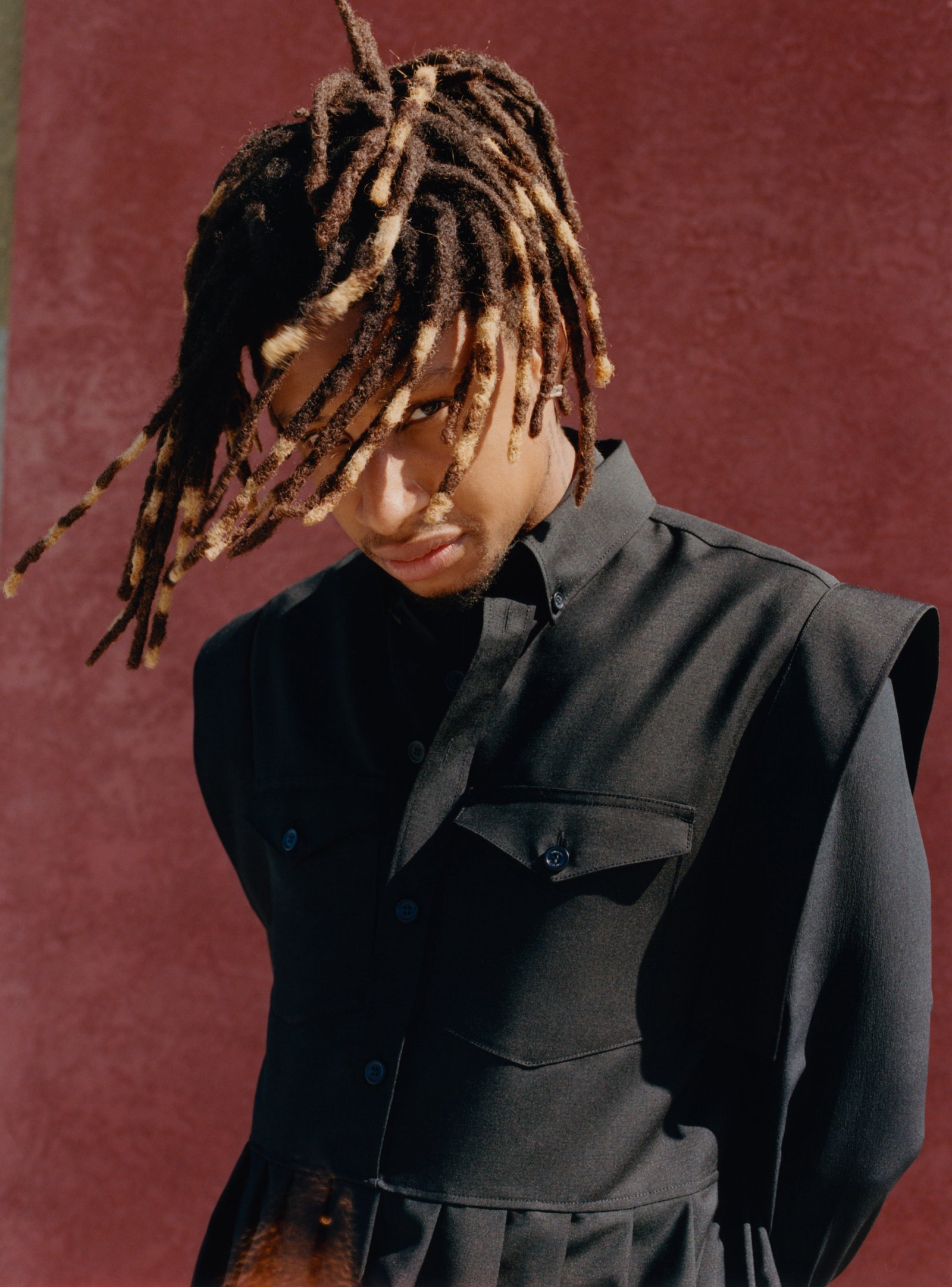

Brick wears hoodie, shorts and sneakers BURBERRY.

‘Surfing is therapeutic,’ muses producer, DJ and creative director Justin ‘Brick’ Howze. ‘It fully disconnects me from everything that I perceive as real when I’m not in the water.’

During the write-off, more commonly known as 2020, Brick found himself in the same boat as the world-at-large, given time to do some urgently needed soul-searching – thanks to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis. Seeking to expand his repertoire of talents, he bounced from tennis to running to BMX riding, before settling on surfing after seeing a street vendor selling boogie boards.

Despite living just forty-five minutes from the beach, surfing was uncharted waters for the creative, but quickly became something of an obsession and unveiled a feeling like no other. ‘You’re just so present, as present as you can be, especially when you’re riding the wave, you’re on a force of nature and you’re absorbing the energy that has been bouncing back from the shore since the dawn of mankind,’ he explains. ‘You’re not thinking about what you’re going to eat, or when you’re going to get your next check, you’re not thinking about how much gas is in your car, or your girlfriend, you’re not thinking about anything.’

Driving back and forth to the beach on a daily basis, the fledgling surfer learned the ropes watching videos on YouTube, but finding his feet soon became the least of his worries. Brick quickly found himself in a position, uncomfortably familiar for Black people; first facing microaggressions, before being involved in a full- blown racist altercation from another surfer on the beach. ‘I super innocently decided to try surfing, but once I got there, I was hit with harsh realities,’ he shares. ‘I started noticing microaggressions that I’m experiencing every day and then the day this dude calls me a n***** and twenty people stood around and did nothing, I realized. It’s mad frustrating to show up and people are making my life more difficult because I’m Black.’

Brick wears hoodie and shorts BURBERRY.

To dwell on the events does a disservice to Brick, it’s what he did next that matters. ‘I realized that this place is fucked up,’ he says, ‘and something needs to be done about it, and it’s going to be me because I don’t give a fuck.’ That something is Ebony Beach Club – formerly known as Black Sand – a collective-cum-safe-space, set on correcting the false narrative that surfing is only for white people. ‘Once that one thing happened, it just blew everything out of proportion and it got so much visibility,’ Brick explains. ‘We’ve built a community with all these other Black surfers and made big waves, no pun intended, in the whole surf community.’

Founded with fellow Black surfers slash creatives, Gage M. Crismond and Tre’lan Tillman, the events that led to the collective’s creation revealed that Black people and surfing appear to mix like oil and water. ‘Surfing dates back to the 1800s, but the 40s and 50s is when surf and pop culture came together. It’s all white history in mind though,’ Brick explains. ‘That’s the beautiful thing about what we’re doing now, we get to completely rewrite it and re- imagine it, uninfluenced by anything. This is the Black experience with surfing.’

In fact, the rebrand to Ebony Beach Club, is a nod to surfing's racist history. The original Ebony Beach Club – opened by Black entrepreneur Silas White in 1957 – was similarly created as a safe space for Black people to enjoy the beach. But, just two months after it opened, the city of Santa Monica claimed it needed the space to create car parking, despite available empty buildings in close proximity, and it was promptly shut down. ‘There’s not too much historical documentation about it, but there’s definitely a history of Black people being kept off the beaches,’ Brick reflects. ‘Localism has created a gang culture within surf and if you’re not from the area, you can’t surf. How can we start anywhere if Black people aren’t allowed to be from anywhere?’

“The root of the problem is that there’s no visibility or representation, so just being able to see that Black surfers exist, is so important,” ... “Even if you don’t surf, it serves as a metaphor for all these different spaces where we’ve been boxed out of. It’s not just about telling white people that we deserve to surf, it’s also about telling Black people that we’re allowed to do this. We can show up and do our thing, even if we felt we couldn’t.”

More positively, the new and improved Ebony Beach Club has already made a bigger splash, recently culminating in the Peace Paddle – a collaboration with fellow Black surf collectives including Textured Waves and Color The Water to bring more than 100 Black surfers together in a stance of solidarity. ‘The root of the problem is that there’s no visibility or representation, so just being able to see that Black surfers exist, is so important,’ Brick remarks. ‘Even if you don’t surf, it serves as a metaphor for all these different spaces where we’ve been boxed out of. It’s not just about telling white people that we deserve to surf, it’s also about telling Black people that we’re allowed to do this. We can show up and do our thing, even if we felt we couldn’t.’

‘Even if you look at the Olympics, which first opened up to surfing this year,’ he continues. ‘Everybody was white with blonde hair, but every other sport that America is represented in is mad diverse ... I’m grateful and feel I was chosen to say this shit, it’s long overdue to be addressed, but I feel like we’re breaking generational curses, as cliché as it sounds.’

Brick and Ebony Beach Club aren’t interested in empty promises and saying the right thing though, they’re genuinely putting in the work to smash the roadblocks stopping Black people from getting into surfing in the first place. On the back of the Peace Paddle, the trio are now working on an app to connect Black surfers and help arrange meet-ups and lessons, while ‘surf reparations,’ courtesy of a proposed flagship, remove the expensive costs of wetsuits and boards that dissuade people from lower-income backgrounds from getting into surfing.

Elsewhere, an Ebony Beach Club Festival is on the cards too, in the near future – merging his love of music and surfing. ‘I’m trying to exile surf culture and bring it to a new space that’s never co- existed before,’ he says. ‘We’re on the beach all day listening to great music, as a bunch of Black people are surfing and others are watching. To me, that is Black people having a footprint in surfing and bringing a flavor that it’s never had before.’

Hoodie, shorts and sneakers BURBERRY.

Brick’s optimism is infectious, a clarity he credits to surfing. ‘It’s crazy because you’re literally riding inside a pocket of energy,’ he enthuses. ‘You genuinely can’t think about anything else and your brain slows time down so you can make micro adjustments with your feet. You can’t really teach it; you just have to feel it and learn how to flow with it.’

‘When I say I feel closer to God, it’s the best way to sum it up. It’s like you’re above Earth in a way. The hard part of surfing is what stops 90 per cent of people from getting into it, but when you get past it, you unlock everything,’ he concludes. ‘Forget uncertainty or sharks. Are you afraid of getting into your car and driving because you could die there? You’ve got to be fearless and have a good time no matter what happens, just do it!’

After only a year of catching waves, Brick is understandably proud of how far he’s come and the lessons he’s learned along the way. The gratification from surfing and the way it’s become part of his life is something he wishes everybody could experience – a wish that will somewhat be fulfilled thanks to the work that Ebony Beach Club is doing and continues to do.

‘I’m not doing this thing that we do for thumbs up from white people, respectfully, it’s not for them,’ he’s quick to clarify. ‘There’s a lot of supportive white people who have helped us use our voice for good and we appreciate it, but ultimately this is for Black people to have a place to go. I want to get 1000 Black people surfing, the concept of having that many Black people in the surf community in Southern California would be gigantic. If we show up 50- or 100-deep to Surfrider Beach, the whitest, most elitist place, we’re making history.’