Awol Erizku's Cosmic Affinities

This story appears in Justsmile Issue 3, Reflections are Protections.

Photography Shane J. Smith

Text Jonathan Jayasinghe

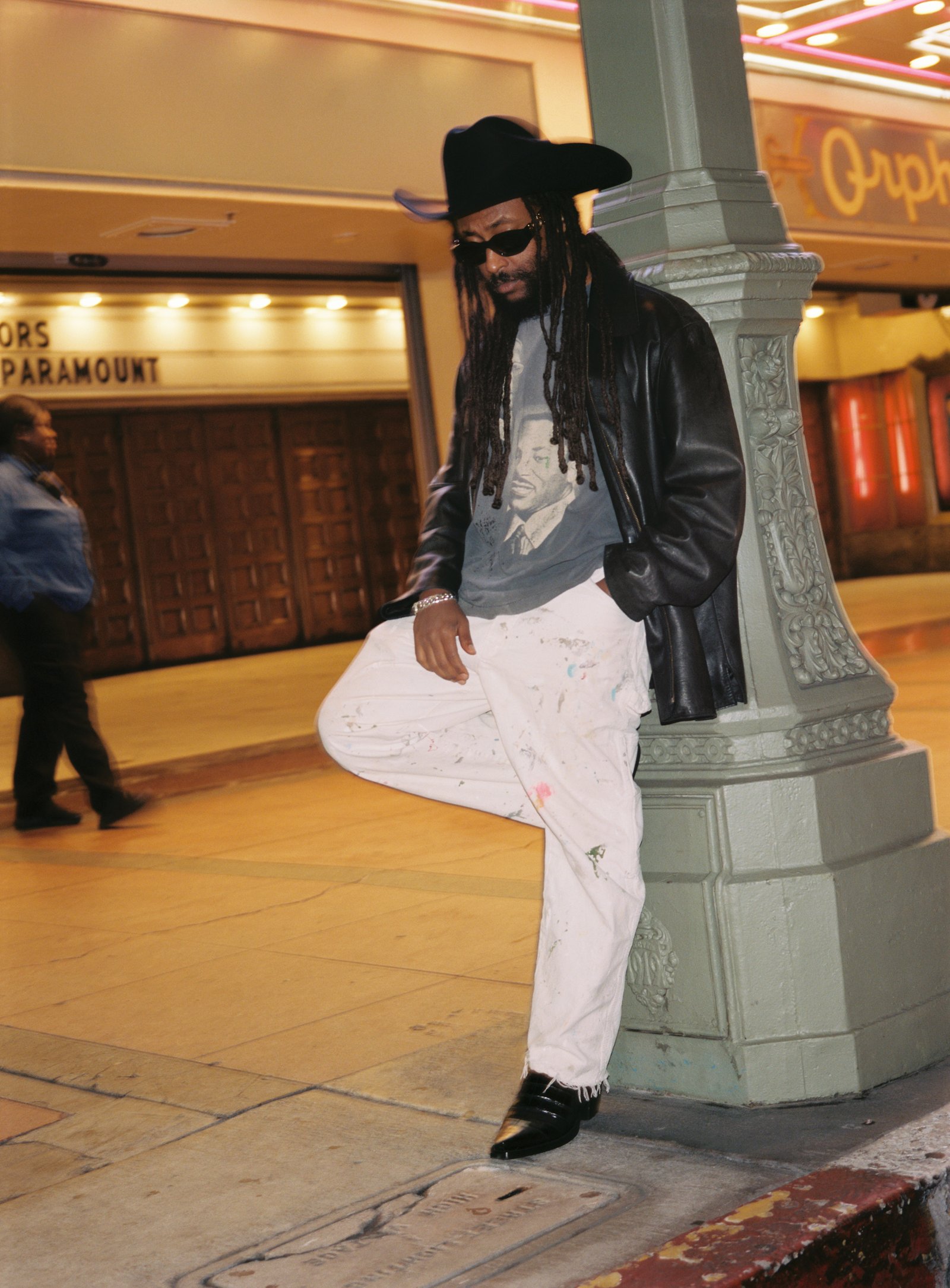

Awol Erizku photographed in Los Angeles, California by Shane J. Smith.

In one of the many dynamic juxtapositions found throughout the artist Awol Erizku’s recently published monograph, Mystic Parallax (2023), we see an image of a young man resting in perfect poise. His head is crowned with cornrows, his neck draped in gold chains and a tarantula is perched upon his cheek. Facing the portrait is an image of an open alligator skin briefcase filled with ice cubes, lit by monochromatic blue light. The space in-between the images conjure a number of disparate associations: The artist David Hammons selling snowballs on the streets of New York, the atmosphere of menace in the opening scene of Hype Williams’ Belly, Arthur Jafa’s articulation of Black ‘cool’ as grace in the face of persistent ambient threat…

It’s these affective proximities and the unexpected associations – they invoke that drive of Erizku’s interdisciplinary work, which includes painting, photography, sculpture and film. Initially garnering a devoted following from posting enigmatic and iconoclastic works, like Girl with a Bamboo Earring, 2009 on Tumblr and Instagram, Erizku’s work has since appeared on the walls of major galleries and museums – as well as within the glossy pages of fashion magazines. From his enigmatic still lifes that blend contemporary iconography with ancient ritual, to his deeply perceptive portraits of the likes of Beyoncé, Bad Bunny and Michael B. Jordan. Erizku’s practice is expansive and relentlessly focused on exploring the ineffable matter of Black imagination.

The release of Mystic Parallax marks a milestone in Erizku’s career, functioning as a comprehensive collection of his work to date and an opportunity to discover fresh perspective within his oeuvre. Flipping through the handsomely bound volume, reveals a continuum of technique and echoes of ongoing thematic obsessions; hip-hop symbolism, art historical intervention, the mystery and majesty of the natural world, the reclaimed debris of pop culture, to name a few. Bodies of work like his series of ‘Reclining Venuses’ (2013) reimagine familiar art history idioms, intervening Blackness and a global perspective into the Western, white-dominated canon. They sit in conversation with works like his ongoing series of assemblages, that place historical artifacts, cultural ephemera and everyday objects into wryly composed still lifes and push his practice into new realms of abstraction.

Front cover of Awol Erizku: Mystic Parallax (Aperture, 2023); cover image: Awol Erizku, Nefertiti-Miles Davis (Silver) (detail), 2018. Courtesy the artist.

Alongside the images, insightful writing by Doreen St. Felix, Ishmael Reed and Erizku’s longtime champion, Antwaun Sargent, offers rich context for the artist’s multivalent practice. The overall effect is a beguiling look at an artist developing a singular language, a glimpse into an archive of cosmic affinities.

Here, Awol discusses the makings of Mystic Parallax, his notion of Afro-Esotericism and the eternal allure of Nefertiti.

Jonathan Jayasinghe: Throughout your career, you’ve had a very considered, yet adventurous approach to how your work is exhibited. How does this monograph play into the ongoing practice around how your work is exhibited?

Awol Erizku: Publishing for me, is not necessarily a new thing. I self-publish through my studio, Esoteric Publishing. I've published my own exhibition catalogs over the last three years. I published a book called Infinity (2020), which has no text and is all images of the candles, and other things that people would leave at the Staples Center for Kobe. So there's a conceptual grounding for this type of work, and it is part of my practice. But I think that something like a monograph, especially with Aperture, is obviously on a different level. Working on the monograph was a moment for me to engage with my own work at a different sort of level. I had to go back and dig in the archive to kind of make sure that it would cover the A-Z of my work. It's partially a monograph, it’s partially an artist’s book, it's really a lot of things. I look at it as a multivalent sort of publication and depending on how you approach it, you'll have a lot to take away from it.

Awol Erizku photographed in Los Angeles, California by Shane J. Smith.

JJ: A lot of your work, especially in the assemblages or still lifes, is about creating unexpected juxtapositions that give way to new meaning. In the context of the book, it then becomes not just the objects within the images, but then multiple images facing each other and being placed in affective proximity to each other – which adds further dimension to the individual works and opens up whole new universes of meaning.

AE: Yeah, you're spot on. When you see the book in its tangible form, it's a whole different sort of transformative experience. The one thing that a publication like this allows me to do with my work is find those in-between moments. The book format allows you to kind of create these transformative moments.

For example, there's a spread where it goes from Teen Venus with a J. Cole spread into a still life where there's an Egyptian cat. And as you fold the pages themselves, you can see these relationships emerge through their proximity. It’s definitely done with the intention of generating new connections and more reads that someone may not get from just seeing these individual pieces on the wall.

Awol Erizku, Malcolm X Freestyle (Pharaoh’s Dance), 2019–20; from Awol Erizku: Mystic Parallax (Aperture, 2023). Courtesy the artist.

JJ: There’s been a lot of conversation in recent years about the limits of ‘representation’ in the art world. I think we can all agree that representation is important, but it’s really just a baseline, a point from which to explore and invent and inquire more deeply. You talk about your work using ideas of ‘historical intervention’ or ‘Afro-Esotericism’. Could you talk about your approach, in the context of the broader category of art interested in Blackness and identity?

AE: You know what's really sad is that in 2023 we still have to talk about these things in an institutional sort of format. As you put it, it is the baseline. For me, it's where I start, but there are many more ideas and concepts that are far beyond that conversation of race and representation, for me.

When you put shows together, on an international scale for example, what often ends up happening is you have to have these sorts of conversations to make the work palatable, so that other people are able to access it, so that it's not simplified to, ‘I see a Black man in a photograph, therefore this work must be about Blackness only.’ In reality, I think most of the work that you see in that book, there's a fair amount of images in which the Black body is the baseline. It's where I start and then I kind of branch off from it.

Awol Erizku photographed in Los Angeles, California by Shane J. Smith.

I had the conversation around representation early in my journey as an artist, with work like Girl with a Bamboo Earring and that whole series. For me, I'm trying to touch on a more sophisticated set of concepts that allow for more universal connections, in terms of race, representation, whatever you wanna call it.

Let me put it to you this way: When you’re in school, you sort of get indoctrinated by these histories that don't speak to your own personal history or lineage. And obviously, your main concern will be, ‘Well, how do I interject my own experience or histories into this?’ So a lot of the early work speaks to that, right? I would go to the MoMA or any sort of big institution, and if I felt like the people that I care about are being left out, my first reaction will be, ‘How do I put these missing pieces back into this bigger conversation?’ So it's less about representation, it's just a baseline from which to kind of Trojan horse these bigger concepts and ideas.

‘When I talk about Afro-Esotericism, I’m thinking about things from the everyday of Black life, from the mundane all the way to spiritual practices. As Black creators, there are certain things that we just have a cosmic affinity towards.’

JJ: In that regard, it’s true that a lot of Black cultural product is asked or required to be accessible to non-Black people. In this case, is the idea of Afro-Esotericism about a desire to be illegible, or opaque?

AE: When I talk about Afro-Esotericism, I’m thinking about things from the everyday of Black life, from the mundane all the way to spiritual practices. As Black creators, Black individuals, there are certain things that we just have a cosmic affinity towards. Our way of life, our way of being in the world. There are things that we respond to in a very specific way. Things that resonate with us on a level of, ‘If you know, you know’. Like being on campus and nodding your head to another Black person that you’ve never met before, but knowing that you both share a similar struggle in whatever space this is that you’re in together. Afro-Esotericism speaks to that everyday knowledge and practice, but on a conceptual level and an international scale.

‘I'm not trying to teach anything. The only thing I really push in that way is Black imagination and the idea that anything is possible.’

JJ: It’s an intuitive and sort of shared knowledge. It's also the kind of thing that when you try to articulate it or theorize around it, when a lot of foundational theory is not even set up to account for such things, it can’t really be contained or articulated in that way.

AE: Exactly. For me, the idea of Afro-Esotericism is a sort of manifesto, or philosophy to speak on this knowledge and these practices that we know and share collectively. Whether that's African masks or jazz or improvisation … And all of that sort of trickles down into how I work in my studio. I think about how ideas come to me, and I often think about it in terms of how jazz musicians improvise. Sometimes I’ll be in the studio and I'll receive a note or two, and I'll improvise from that. Other times, it’ll be more like sheet music and I'll have to work with it to arrange it. So in a way, I'm a bit of an impresario or a conductor of ideas, and I'm just building upon the work of those who came before me.

To come back to your question, yes there's an opaqueness to what I’m doing. But it all depends on the audience. I don't necessarily make work to be hermetic. I work from my own sort of disposition and whoever connects with it is who it’s for. And there's always different ways to engage with the work. I leave room for exploration and new possibilities. It's never prescriptive, never didactic. I'm not trying to teach anything. The only thing I really push in that way is Black imagination and the idea that anything is possible.

Awol Erizku, Lion (Body) I , 2022; from Awol Erizku: Mystic Parallax (Aperture, 2023). Courtesy the artist.

JJ: Of your many portraits of iconic cultural figures, which include Beyoncé, Michael B. Jordan, Bad Bunny, Tessa Thompson, Amanda Gorman and on and on, I have a personal favorite. It’s the editorial of DMX for the October 2019 issue of GQ. Could you talk about your approach to photographing iconic, larger than life figures, using that particular shoot as an example?

AE: I’ve never accepted a commission like that for clout. I’ve turned down many opportunities where I didn’t feel like my voice was relevant to the subject, or that I didn’t have a genuine connection, whether directly or indirectly, to the person. Anyone that you see in the book that I’ve photographed, there’s a genuine connection to them that I feel.

With DMX, for me it was about having grown up in the Bronx, and being raised on that era of New York hip-hop. He was one of our legends and so the commission made perfect sense to me. In terms of how I approach each of these subjects, I start from a place of asking myself, where this person is at in their career and what kind of images they need to communicate that, while also building on their legacy. I approach them sort of as visual statues, in a way…

JJ: Something like monuments, maybe?

AE: Yes exactly, visual monuments. I remember very specifically, Mobolaji Dawodu, the stylist, and I were discussing what we were gonna do with X and we finally went into the fitting. He was at this hotel in Yonkers and we were just vibing, chilling, chopping it up, trying on clothes. And I said to him, ‘You know, X, we have to do something different. Like I don't want to do anything with dogs.’ He was like, ‘Bro, bro, I'm a dog.’ But I was like, ‘I grew up seeing those images of you and everybody thinks that's all you are. And I think you’re a more complex person and we wanna show that. We wanna show the journey that you've been on and the new phase that you're entering.’ I just remember thinking like, people have this idea of him already, so why don’t we play with those existing perceptions.

From there I was like, let’s do a Noah's Ark kind of theme and bring in different types of animals. I was like, let's get a python, let's get a six-foot iguana. We just brought in all these animals and we're like, let's see how you vibe with them. He was like, ‘Bro, this is a big Python…’ But he was so down with the concept, he just saw the vision and he was so cool. He even stuck around later than he needed to, to make sure we got all the shots we needed.

Awol Erizku photographed in Los Angeles, California by Shane J. Smith.

JJ: Something that stood out to me looking at your work this time around, was your unique approach to perspective within the frame. Photographically, in the portraits as well as the still lifes, there’s a deep focus combined with kind of flat environments, which makes for a unique visual texture somewhere between painting and photography. Could you talk about technique a bit, and how your approach to technique has developed over time?

AE: If you look up the earliest photo in this book, it’s from like 2009. So that’s over ten years of work in there. I've been building this vernacular right, like this visual syntax, over time. I could’ve put out a book of the series of ‘Reclining Venuses’, for example, back in 2013, if I wanted to. But it would have been kind of a one-dimensional thing, where the vision wasn't complete. I’ve been developing and stacking these visual motifs and working with these different techniques like building blocks.

A great example is this spread on pp. 98-99, these two hoops. This is what I mean when I talk about the notes coming to me, right? I knew that there was a form that I was trying to make, starting with the hammer, which is sort of a recurring motif for me. It’s a blunt object, right, but also in hip-hop it refers to a gun. So it's kind of a code. And at the time, I had a lot of Future playing in the studio. This was ‘Dirty Sprite’ era probably, that mixtape era. So the music I was listening to at the time was seeping through the work, seeping into the images. The image on the right is from around 2018. But I put those two together simply to show how this idea evolved over time. With the early version on the left, it’s visually pleasing or interesting, but there’s not much substance there. And then the one on the right is a more fully developed idea. If the one on the left is a single note, the one on the right becomes sort of a composition.

All of this work came with time. Something that often happens with artists is that you put out something too early and then somebody else runs off with your idea before you’re able to explore it more deeply yourself. It's happened to me in the past. But these moments in the book are very important for me because again, it shows that there's actually a structure and concepts that are much deeper that we may not be able to unpack in a single conversation.