A room of Kevin Beasley’s own

Known for his spatial listening experiences and embedded public works, Beasley brings us into his new Long Island studio ahead of the Gwangju Biennial. Reconfiguring the real into public art and imagination, Kevin Beasley’s practice reworks and reinvents.

This story appears in Justsmile Issue 5, How Do We Belong?

Photography Raphaël Gaultier

Introduction Tony Jackson

Interview Christopher Y. Lew

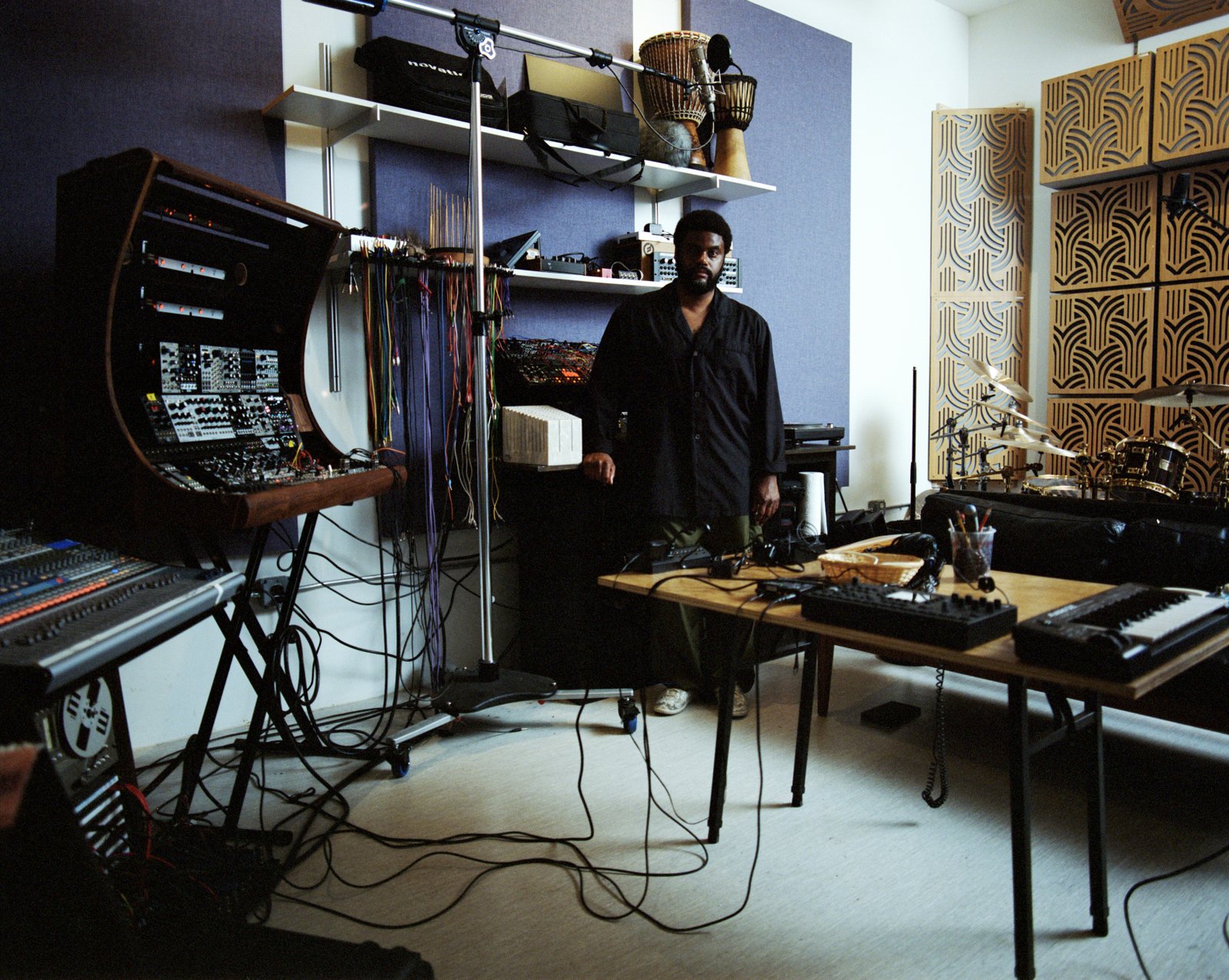

Kevin Beasley in the office of his Long Island City, New York-based studio.

Kevin Beasley has emerged as a dynamic figure in contemporary art, celebrated for his groundbreaking sculptures and sound installations that turn overlooked objects and silenced histories into poignant reflections on culture, politics, and history. In between shows with his galleries Casey Kaplan in New York and Regen Projects in Los Angeles, and ahead of Gagosian’s “Social Abstraction,” a two-part group exhibition held in Beverly Hills and Hong Kong, curated by Antwaun Sargent, Beasley sits down with writer and curator Christopher Y. Lew, whom he met over a decade ago, when Lew was a curator at MoMA PS1 and Beasley was an artist-in-residence at ISCP. Together, the pair discuss Beasley’s creative journey, and offer Justsmile an exclusive look into his new Long Island City studio.

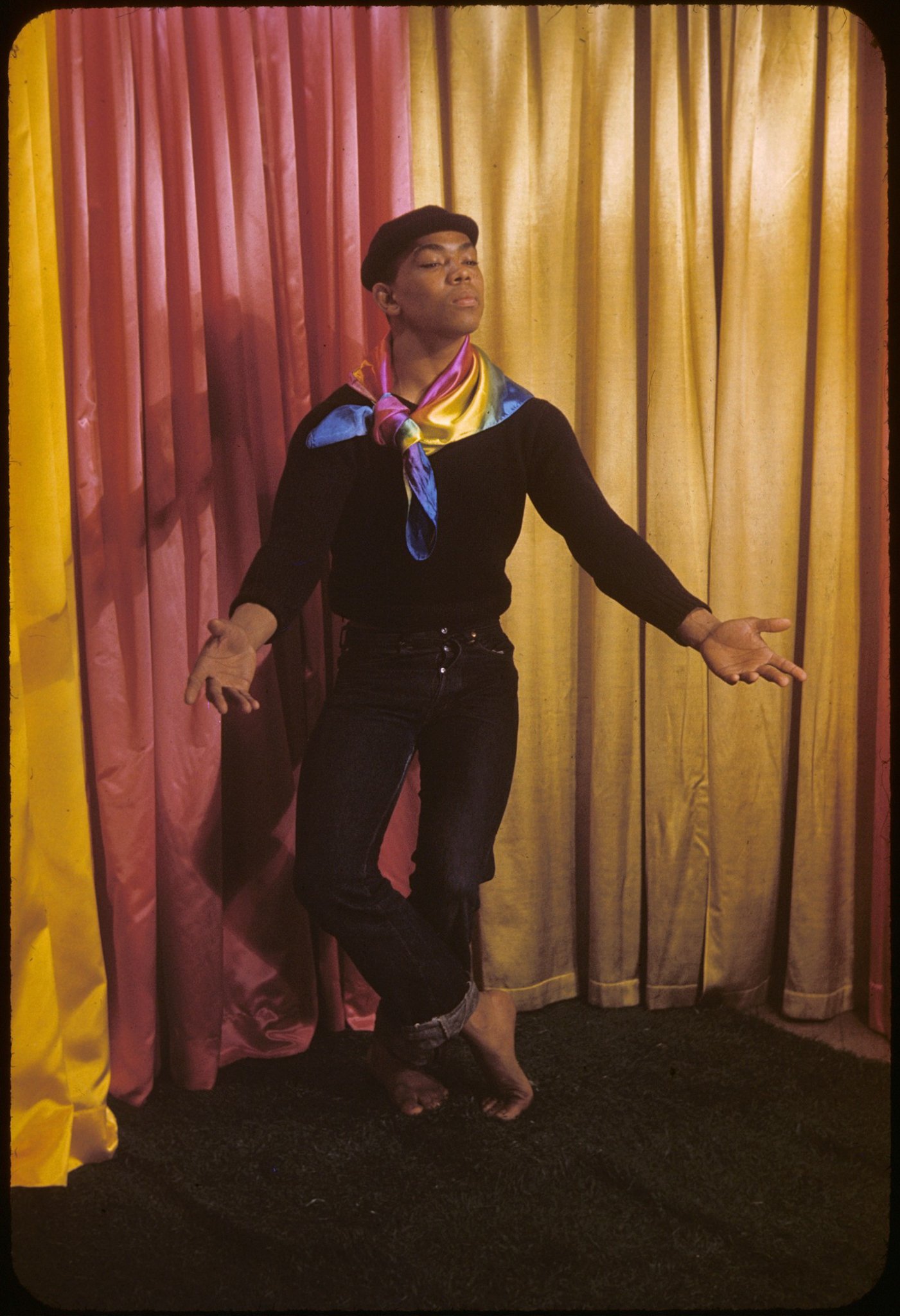

In conversation with Lew, Beasley shares insights into his latest projects, his work on the Gagosian show, his involvement in Ralph Lemon’s performances at MoMA PS1, and the community garden he established in New Orleans in lieu of creating a temporary installation. From shredding garments into confetti for sculptures to taking on large-scale public art projects, Beasley’s work is defined by a dialogue between local textures and global concepts. Reflecting on his expansive new studio space and his ongoing engagement with multi-scale works—such as his reimagining of modernist forms for the Gwangju Biennial—Beasley affirms that his art is not just a practice but a lifestyle of continuous reinvention.

Christopher Lew: When did you know you were an artist?

Kevin Beasley: I think it started really young. I was probably about four. Maybe my consciousness of being an artist was not fully there as much as it was just about making images, drawing a lot, and then also giving those drawings away. That was really important. I would make them for people and then hand them out—like, drawings of Ninja men, and cars, and different kinds of things. But I think that the mature decision to then recognize that as essential to who I was came when I started high school. [In elementary school], art classes were considered extracurricular activities and not really essential. I never actually had an art course until I got to high school. I took some private lessons, when I was 10. I would oil paint and do things, and I pursued it pretty seriously. But by the time I got into art classes in high school, it felt like a part of my identity. So I was really adamant about taking as many art classes as I could, and kind of gearing myself to go to school for it.

CL: So, even when you were going to undergrad, you really already had that in mind, or [a sense of] how important that was to yourself.

KB: I went to the College for Creative Studies. I went there for automotive design and that was super essential, because I was melding multiple interests and disciplines together. But I was also thinking about it from a practical sense, like, "Oh, if I'm working for the auto industry, I could make a pretty good salary or income, have a career and it'd be exciting. I'd probably get to travel." I just had these ideas around what it would afford me and I didn't make it through because I was like, "This is actually not what I want to do." And that's when it became more viable for me to really think, "I should just make art." Creative freedom was way more important than having healthcare or something, so I was like, let me focus on that. And it became a surprise, because the school fostered ways for fine arts or craft students to actually sell their work to the general public, so I had a little taste of that in undergrad, and it didn't seem so farfetched. You meet artists, you're watching all the Art 21s, and you start to inform yourself around the bigger structure of how people are making a living and making an impact with their work and reaching different audiences.

CL: Yeah, that it was modeled, that it was doable, and that you could have a life doing it.

KB: Yeah, and that I didn't have to, like, cut off my ear or something.

Creative freedom was way more important than having healthcare or something, so I was like, let me focus on that.

CL: Thankfully not. And so, to fast forward, you're in a new studio now. How's that and what is it looking like these days?

KB: The studio is still in Long Island City, so I'm not far from the old spot. But it's a much bigger space. It's more expansive. I still have separation. I have an office, there's a little kitchen, multiple bathrooms and different spaces where we're able to engage in different processes, from casting to metal-working to wood. And there’s a general material shop. And then an assembly room, where all of those parts and pieces can come together. We’re in the sound room [right now]. I had to keep my sound booth as an essential part, because... I can't sell my equipment.

CL: I'm glad you've not let go of that. And knowing the sound studio there is still present and central in many ways—

KB: Yeah, totally. It's just a much more generous layout based on what I had before. And it's been super useful just to be able to work on multiple projects at once without having to break something down in the morning and then set up something else and then break that down and then re-set up. The other thing is I can push things along at the same time and move from space to space.

CL: I remember the old space. As finished works were coming out of the cast, it felt a little bit like Tetris to move things around and keep them out of the way as you kept going.

KB: Yeah, it was like, you make a sculpture, and then it becomes a table! I was super grateful to have that space, because it was also at a really pivotal moment for me. I came out of the Studio Museum residency, I had a space at Michael Levine's spot for about a year. Then I moved into another space and I was bouncing around a lot, and then that space wasn't quite what it was before. So when I got into this space in the Silks building, it was the longest lease I had signed. I could be there for a long time. It was bigger than what I thought I was ready for, and I grew into that space and then grew out of it. We worked on our project together in that space. There's just a lot of things that happened there and I felt like, this is really what the studio provides: a lot of growth and the ability to take risks. When you have a space that you really like and it might be a little bit big for you, you're like the three year old with the five year old coat on.

CL: You grow into it.

KB: I think this is, this is kind of a similar thing. We’ve already embarked on some really large projects in here, and it works really great. And we’ve got some more stuff coming up that, scale-wise, is really big—logistically, these multiple parts syncing together.

CL: I know you're in a group show at Gagosian in Beverly Hills right now. Want to talk about some of that work and what that is?

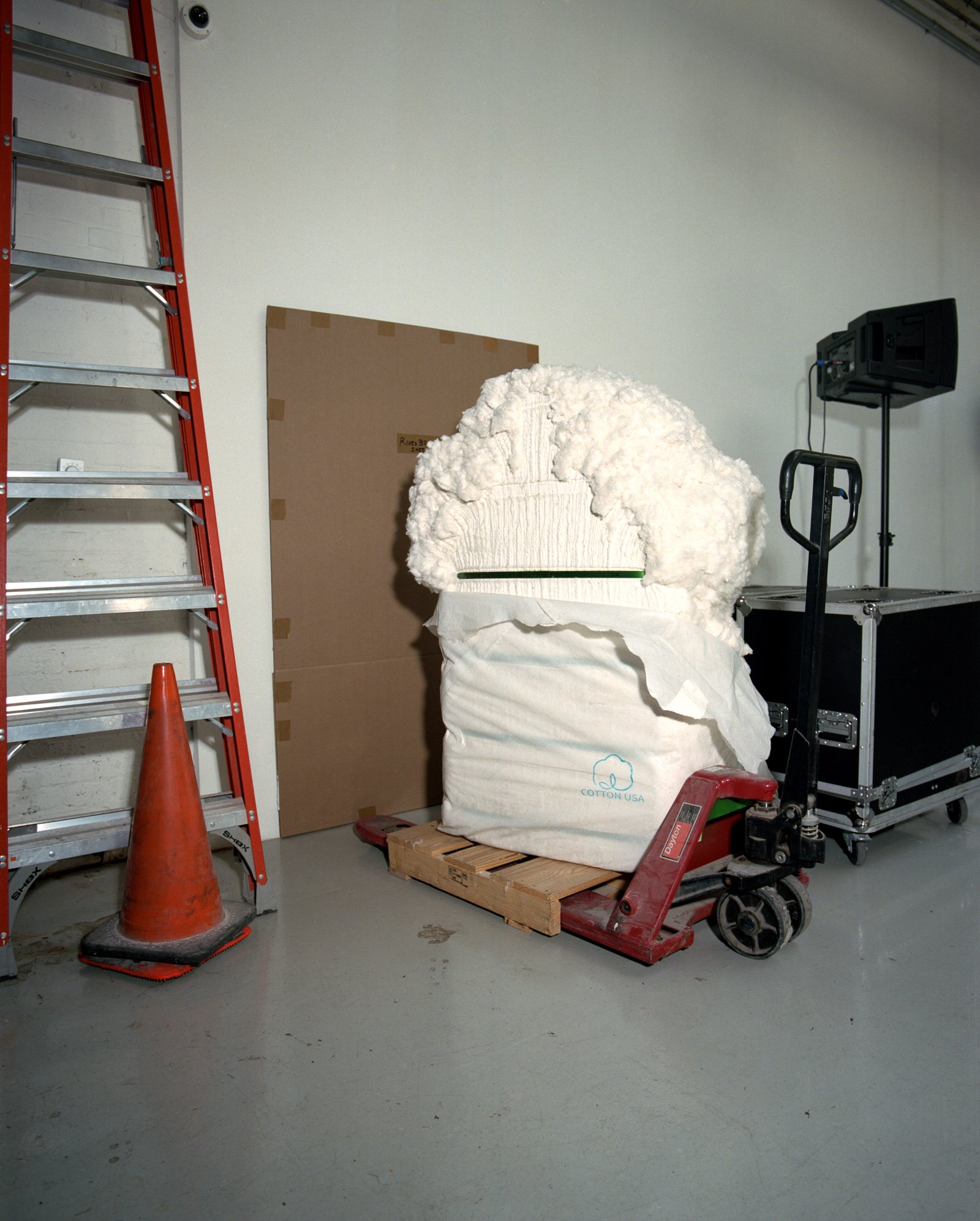

KB: The scale of the work has really shifted a lot, and it's funny. It's like I get into a bigger space and then I want to go small, you know? I want to go tight. These objects satisfied this level of intimacy for me in their scale. In the way that they're generated, they're kind of an offshoot of a body of work that I made that I call “Residues.” The “Residues” are the remaining materials from other sculptures or other objects that I'm making. They end up in these rectangular molds, and the colors, the materials that end up inside them, the way that they're applied—you know, it's all the same process. You end up with something that's very unpredictable, but is kind of a summation of a certain period of time. Like a space that you've been in. I've been working with this stuff for a long time, the resin and the cotton, and now I'm like, "How can I reinvent this? How can I readdress that? How can I learn something else about how to apply it?" These works for that I made for the Gagosian show: I've been thinking about them as windows, or panes, things that you look through because of the layers. I started really thinking, Okay, how do I go in with a certain plan, or really think about color palate? How can I really think intentionally about the kinds of marks and textures that I want to make? Resin cures really fast, so having to make a lot of decisions, or pre-determine some of the decisions, is really important, so that I'm able to respond [to the work] in the moment. But then I can quickly move on to the next color or say, no, this is my palette, [these are the limits] that I can work within, and I can develop them as such. The exercise is an abstraction.

CL: It's kind of the same way that you're using, say, raw cotton from your family's land in Virginia, or old clothing. Now, it's kind of like the literal materials that are coming out of the studio.

KB: Exactly. It's all there, you know, like the dust, even the memory of it. I bought a shredder, like a big industrial shredder—

CL: To shred your own work?

KB: Yeah. When it comes down to it, stuff comes back to the studio, man. That's where it's going. There's a lot of stuff, like offshoots or things that you make that you're like, "Oh, this is kind of funky," or it's a piece of something that's gotten cut off, and then you can process it. I've been throwing garments in the shredder, and you get these confettied little pieces. And for about a year, maybe a year and a half, we were cutting confetti by hand, with just scissors. It was such a time-consuming process. On one end, I really love that: your hand is all in it. But then it was just like, "This is just painful." At some point, you want to shift from just cutting confetti to actually drawing, or casting something engaging in some other part of the process that may need a little bit more attention than, say, the shape of these little morsels of garments. So as much as I’m adamant about the garment being present, I'm also adamant about deconstructing it and using parts from that thing. Because where it's coming from is really just as important as how it sort of arrives as something else. I'm looking for something fresh, or something I haven't seen before.

CL: And in that regard, I think about these resin pieces, and so much of it is about place or the sense of the local. Is that still there for you, or do you feel like you're moving to other things to explore within it and think about the materials?

KB: It's definitely a major part. I think I'm in the space now where I'm kind of like, what is the local in my imagination? Like, it may be less about the local as even having a physical presence that is recognizable, or legible. But it's there, right? Like, the cotton is all very local. The garments are all very local. Or local in terms of there being a very specific access point that I want to elevate in the conversation. Like, the garment [and] the materials are coming from all over the place. But I think that now I'm in this space where I'm like, "What is the construction that I have in my mind around what is, and what isn't, local?" And I've been thinking about that a lot through drawing. And bouncing back to Prospect.5 when I was making those drawings of the Lower Ninth Ward [of New Orleans], there was this desire to connect to the local, but the process, like—I wasn't local at all. I was doing something very remote and very much outside. And [I was] trying to think about what my relationship was to that being the currency of the work, or that being the question around what it is that we're doing.

CL: But it's also thinking about those drawings in relation to—essentially, you created a public garden for the local community [in the Lower Ninth Ward, on land that had been vacant since Hurricane Katrina]. In that sense, it's speaking to a very specific audience. Of course, people come and visit and would travel for it, but I feel like the main audience for that is the people that live nearby.

A bail of raw cotton from Virginia—a recurring motif in Beasley’s practice, a meditation on labor, history, and a tactile connection to his heritage.

KB: Yeah, whether it's the post office guy, the mail guy walking by every day, Sunday morning when everyone's going to church, and they're passing [this garden]. Even some of the unhoused folks that live down there, passing by, or even going on to the site and just being there.

CL: You have drinking fountains, and there's electricity to recharge your phone, right? [And a utility pole that offers the only Wi-Fi hotspot in the area.]

KB: Yeah. And blueberries! There are actual things to consume on the site, which has been interesting, just in terms of how that all functions. I think it's a big question, and I'm not really sure how I land on it in terms of what it’s doing for me, or what it’s doing for the public. What it does for audiences that read about it or see it [is] in a different context.

CL: I feel like that's what public art aims to do. And not all of it gets there, but this certainly does. It embeds itself in a community. It becomes part of that community.

KB: Yeah, exactly. It'd be interesting if, one day, Prospect used it as a venue. I've had conversations with them before about the potential—it's not there yet—but it would be interesting if it started to serve these other purposes or people just started taking over and started using it in particular ways. We're still kind of observing it from that, from that standpoint.

Kevin Beasley in his Long Island City recording studio, where sound becomes both medium and memory.

CL: And what else? What's coming up these days? What are you working on now that you're excited by?

KB: I do have a big public artwork that I'm in the process of making. We've been doing a lot of planning, a lot of R&D, and we start production in October. We're doing a lot of prep. When I get back from Gwangju, that will be the focus and that's going to be a heavy six month slog just to get through all the production for this work. So that's been really exciting. There are other projects on the horizon as well, a few gallery shows in '25 and '26 and, yeah, I think the big thing that was announced is a lot of collaborations and performances with Ralph Lemon this fall.

CL: Yeah, you guys are getting the band back together, so to speak.

KB: Yeah, we're going to stir some things up—

CL: —for his MOMA PS1 show, right?

KB: Yeah. And actually, we’ll do a version at the Walker Art Center Minneapolis that will happen first in October, commemorating his 10 years of Scaffold Room, and then that whole project moves to PS1, which I'm very excited about it. Been working on it non-stop. It's kind of put us in the sound studio a lot, as well.

CL: It's great that that kind of collaboration can keep going and just thinking about him performing within your installation at the Whitney and now you coming into his big show at MoMA PS1.

KB: Yeah, exactly. Although, I think I was in Ralph's show at at the Whitney. [laughs]

CL: Once Ralph comes in, it's his show, right?

KB: Yeah, it's like, he comes in and it's just like, Alright, yeah, this is Ralph's thing now. But then he's like, Don't announce me, don't put my name on the flyer. He makes you think it's your show, and then he takes it over. This will be definitively his show and I'm happy about it, I'm excited.

CL: You know, maybe you could turn the tables on him a little bit when you get in there.

KB: I've been trying, man. [laughs]

CL: That's super exciting. What are you showing in Gwangju? Are you able to speak about that?

KB: Yeah, I've got these five sculptures. Three of them are free-standing, and then two are on the wall. My conversations with Nicola were really about the materiality being very present. He's got this larger framework in terms of how he's thinking about the exhibition from a conceptual level. It was interesting to talk to him, and it wasn't like he was saying, you have to encapsulate the idea of the whole exhibition. He's just like, I really just want the material presence of the cotton and how you've been working with it, he gravitated heavily towards that. For me, it was like he cut the leash on thinking about the material in its solitude, and they become like notes or independent modules. And they're massive, like 6' by 10' and another one is like 2' square by 8', and another one's like 9' by 8' or 10' by 8'. And they're just massive hulking modules of cotton. Then there's two wall-based works that incorporate both cotton and the garments. So there's an evolution in terms of their relationship to this, as you describe it, their relationship to locality, and how that's rendered in really different ways. I think maybe that's as much as I can speak about them, but they kind of become these punctuations or even commentary on modernist formal sculpture, and thinking about "What would Ann Truitt not do?” or “what would Barnett Newman not do?" I think they really function in that way.