Flood the World — Alvin Ailey

Whitney Museum curator Adrienne Edwards discusses the life and career of Alvin Ailey, the subject of her “Edges of Ailey” exhibition, with writer Yaniya Lee. This story appears in Justsmile Issue 5, How Do We Belong?

Images courtesy of The Whitney Museum of American Art

Text by Yaniya Lee

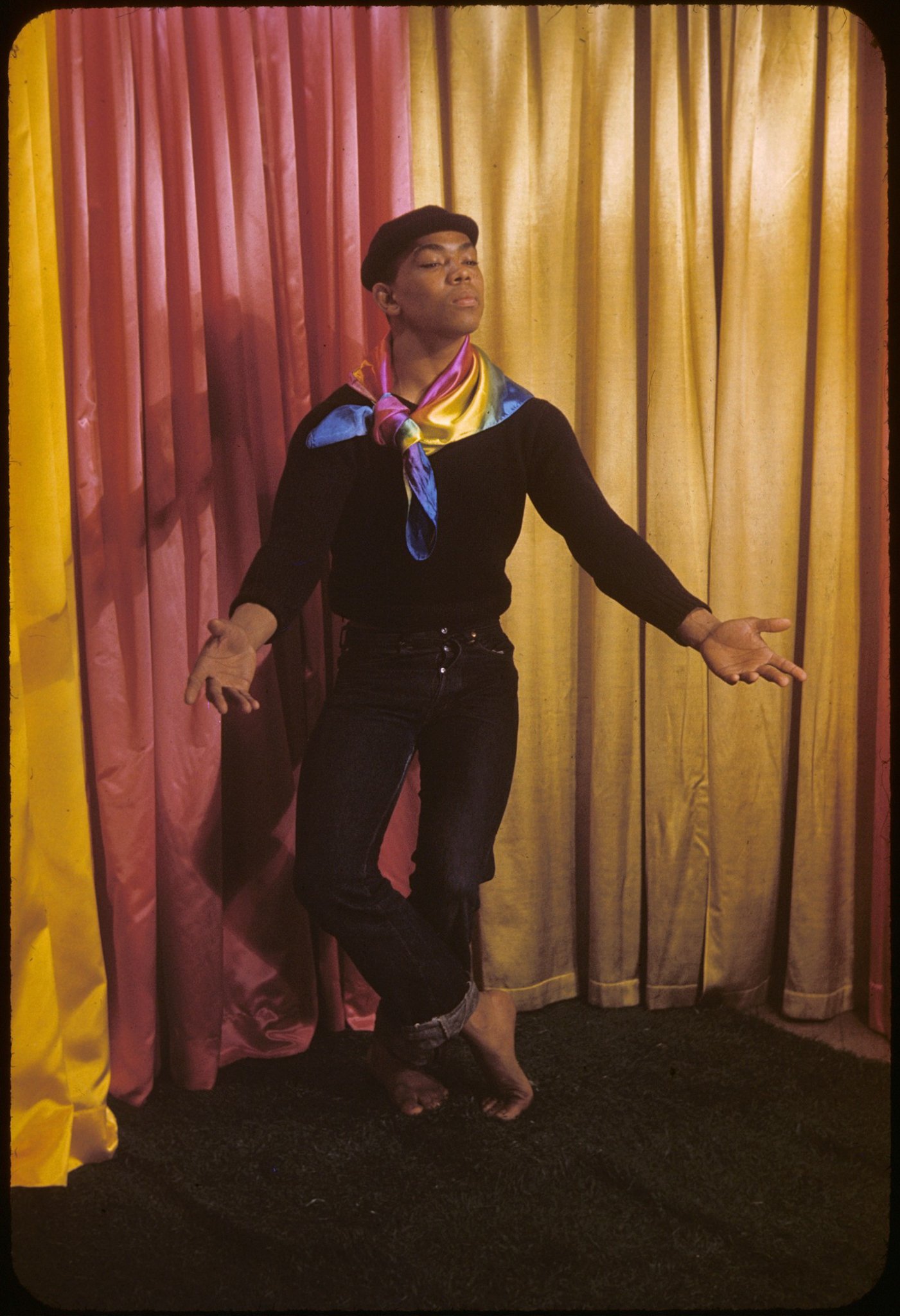

Carl Van Vechten, Alvin Ailey, 1955. Kodachrome color slide, 2 × 2 in. (5.1 × 5.1 cm). Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. © Van Vechten Trust.

Being Black and in the arts is both the same and not the same at all as being Black and in the art world. The contemporary art world has been rapid-cycling for a while now. The institutions that today embrace diversity with a wolfish grin once outright refused our presence, or ghettoized us into ethnic enclaves. Things have changed. And hopefully for the duration. This shift is being heralded by curators, patrons and critics in key gatekeeper positions, many of whom are now shouldering the responsibility of honoring our great artists.

“Edges of Ailey,” an exhibition curated by Dr. Adrienne Edwards at the New York Whitney Museum (September 2024 to February 2025) is doing this very work. The show is a testament to the monumental life, work, and influences of the great American choreographer Alvin Ailey (b. 1931-1989), who is widely credited as one of the most significant artists of the 20th century. As a teenager, the Texas-born Ailey trained for 5 years in Los Angeles with the choreographer Lester Horton; by age 23, he was already dancing on Broadway. Ailey found a home and a community in New York, which was dazzling and resplendent in the wake of the Great Migration — a city where literature was thriving and bebop was innovating and many influential arts movements were coming to a head. Then, in 1958, he founded the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, the famed dance company that would forever change modern dance. He would later go on to open a school, and continue to dance and choreograph until his premature passing from an AIDS-related illness in 1989.

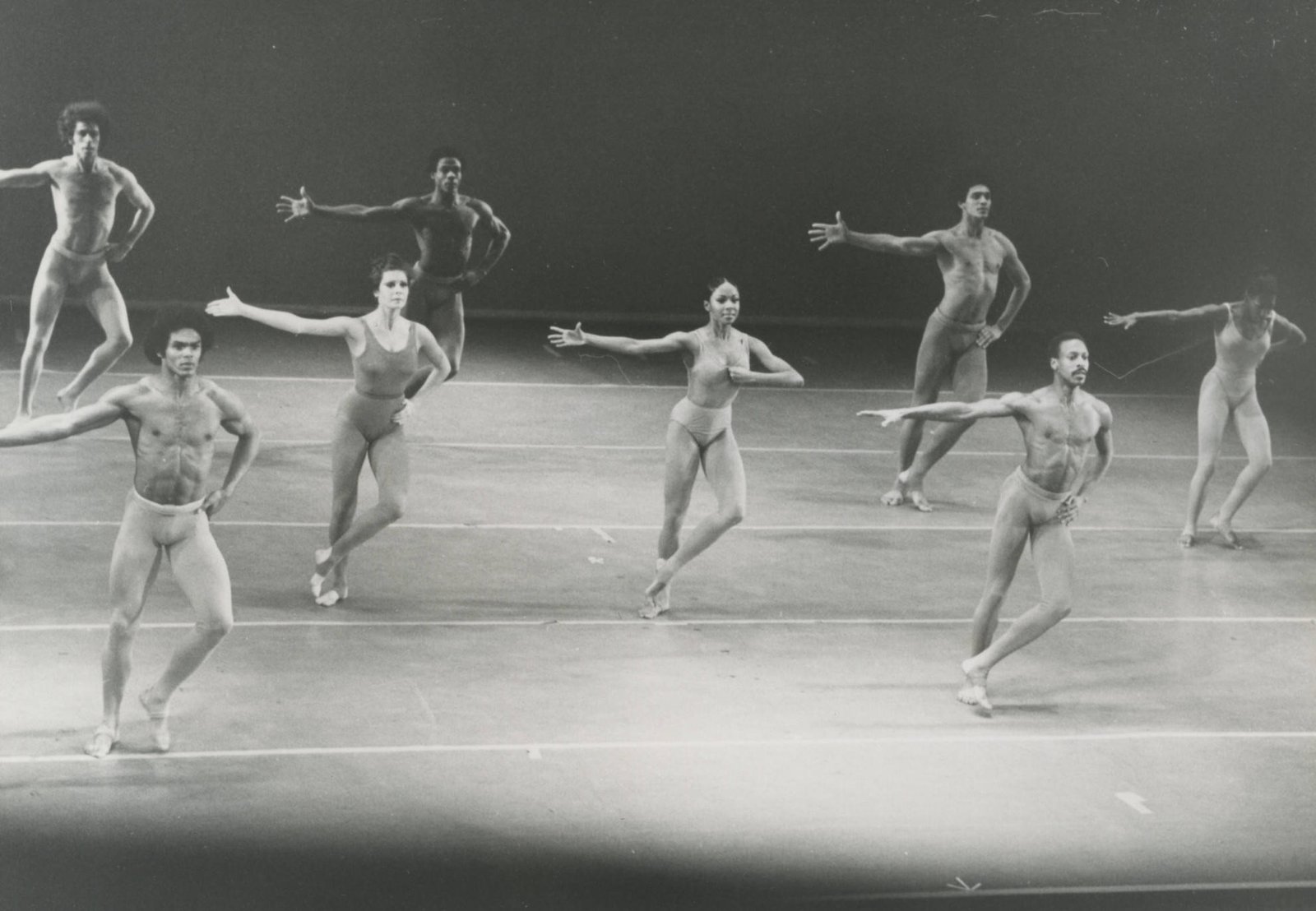

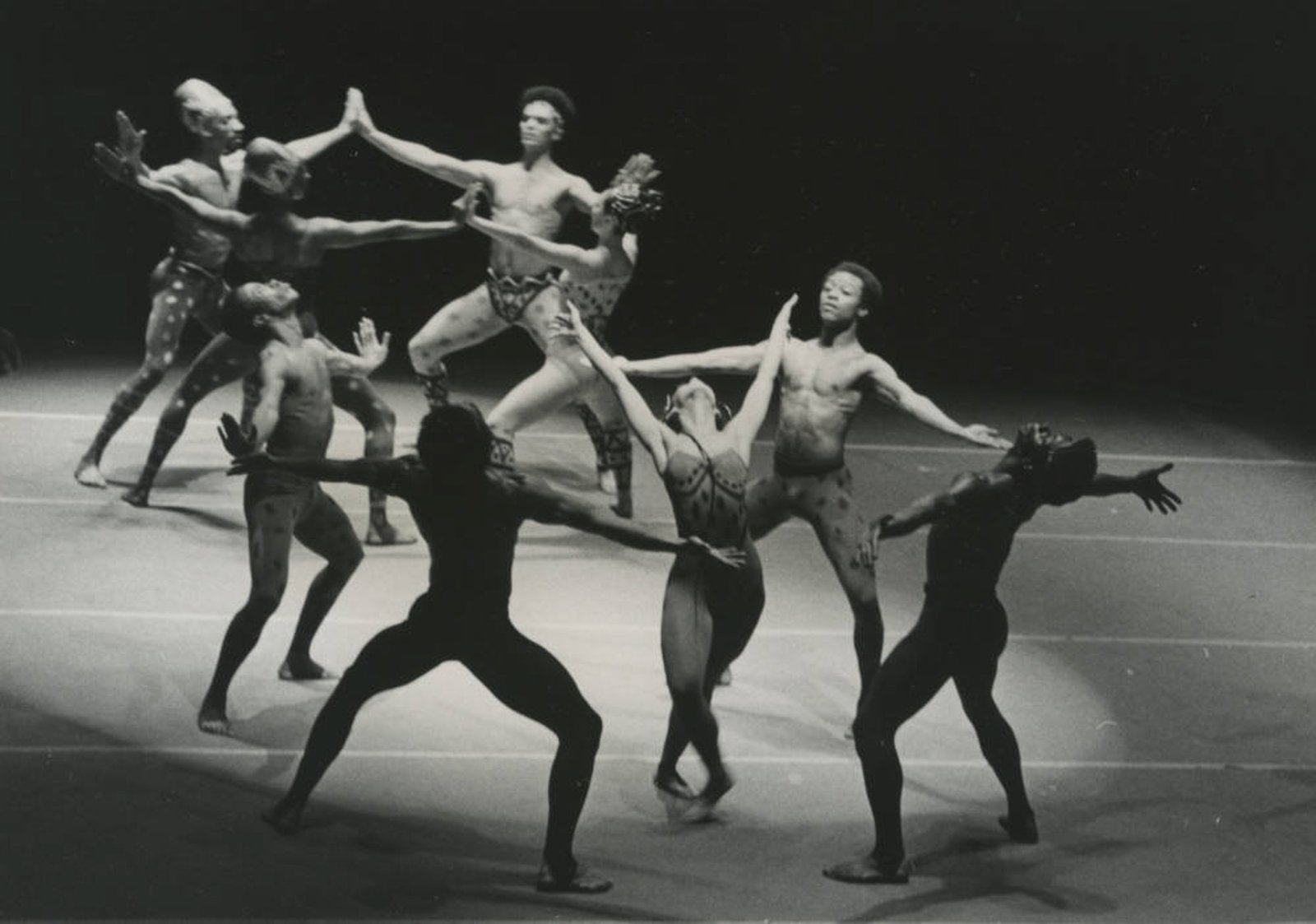

Fred Fehl, Streams: Clive Thompson, Estelle Spurlock, Dudley Williams, Sara Yarborough, Hector Mercado, Kenny, & Christina Gonzales, 1971. Photograph, 5 x 7 in. (12.7 x 17.78 cm). Fred Fehl Dance Collection. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin. © The Harry Ransom Center

This current exhibition brings together works by more than 80 artists, archival material and documents related to Ailey's life, a series of dance recordings, workshops, movies and live performances, all of which, taken together, speak to the artist's expansiveness, his multiplicity, his influences and his influence on others.

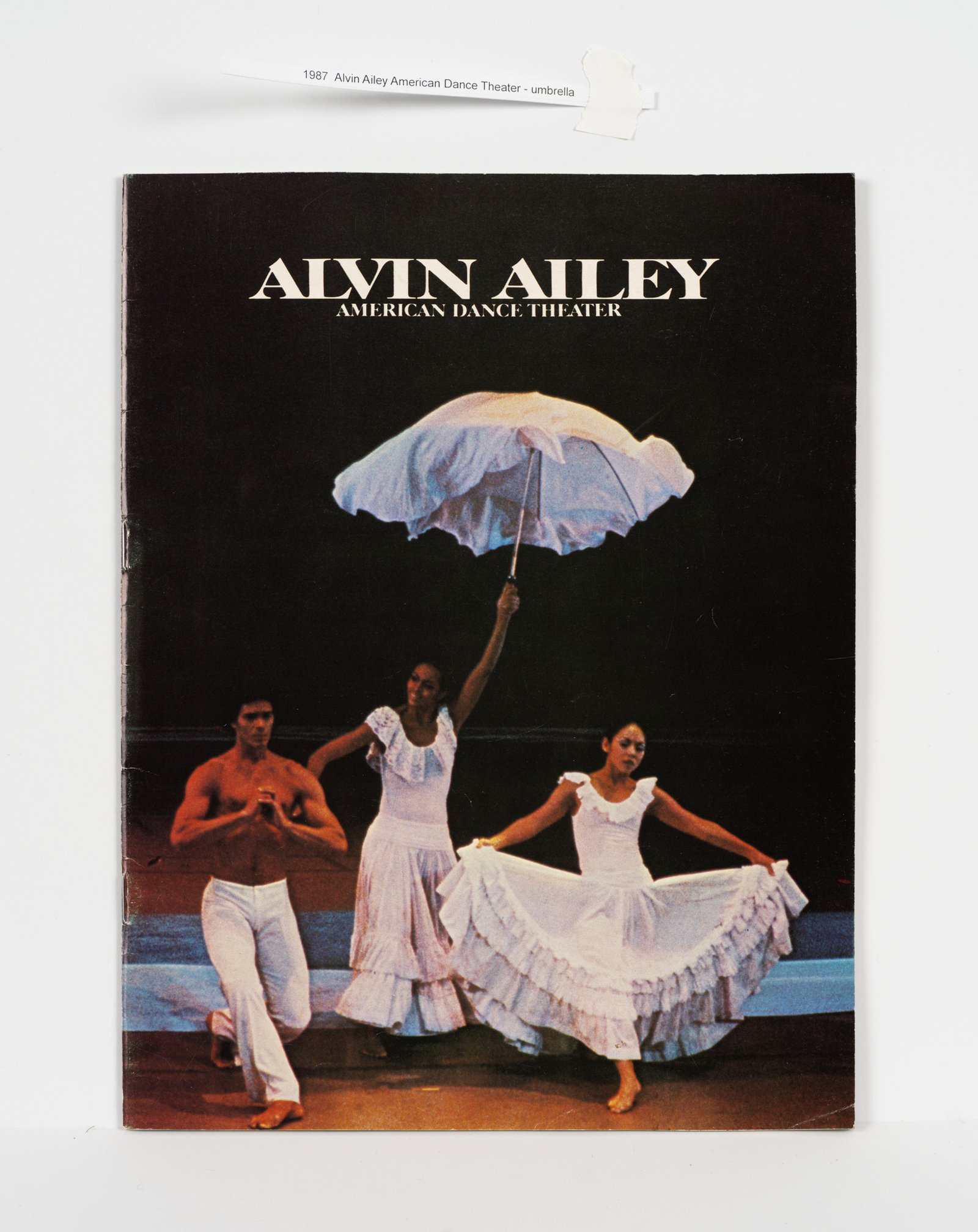

Alvin Ailey Program: Rio de Janeiro Teatro Municipal, 1981 June. Courtesy Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc.

Dr. Edwards has curated at Performa and at the Walker Museum, and has worked with or written about contemporary artists like David Hammons, Pope L. Tony Cokes, Adam Pendleton, Ellen Gallagher, and Julie Mehretu. Before co-curating the 2022 Whitney Biennial, she gained attention for her 2016 group exhibition “Blackness in Abstraction” at Pace Gallery, which included the works of artists like Carrie Mae Weems, Wangechi Mutu, and Glenn Ligon. Dr. Edwards says she developed the idea for the show “in response to the demands placed on Black artists for social content in their art ... Applicable to artwork in any medium, it is an attempt to understand how artists negotiate and exhaust the paradigm of Black representation in visual art.”

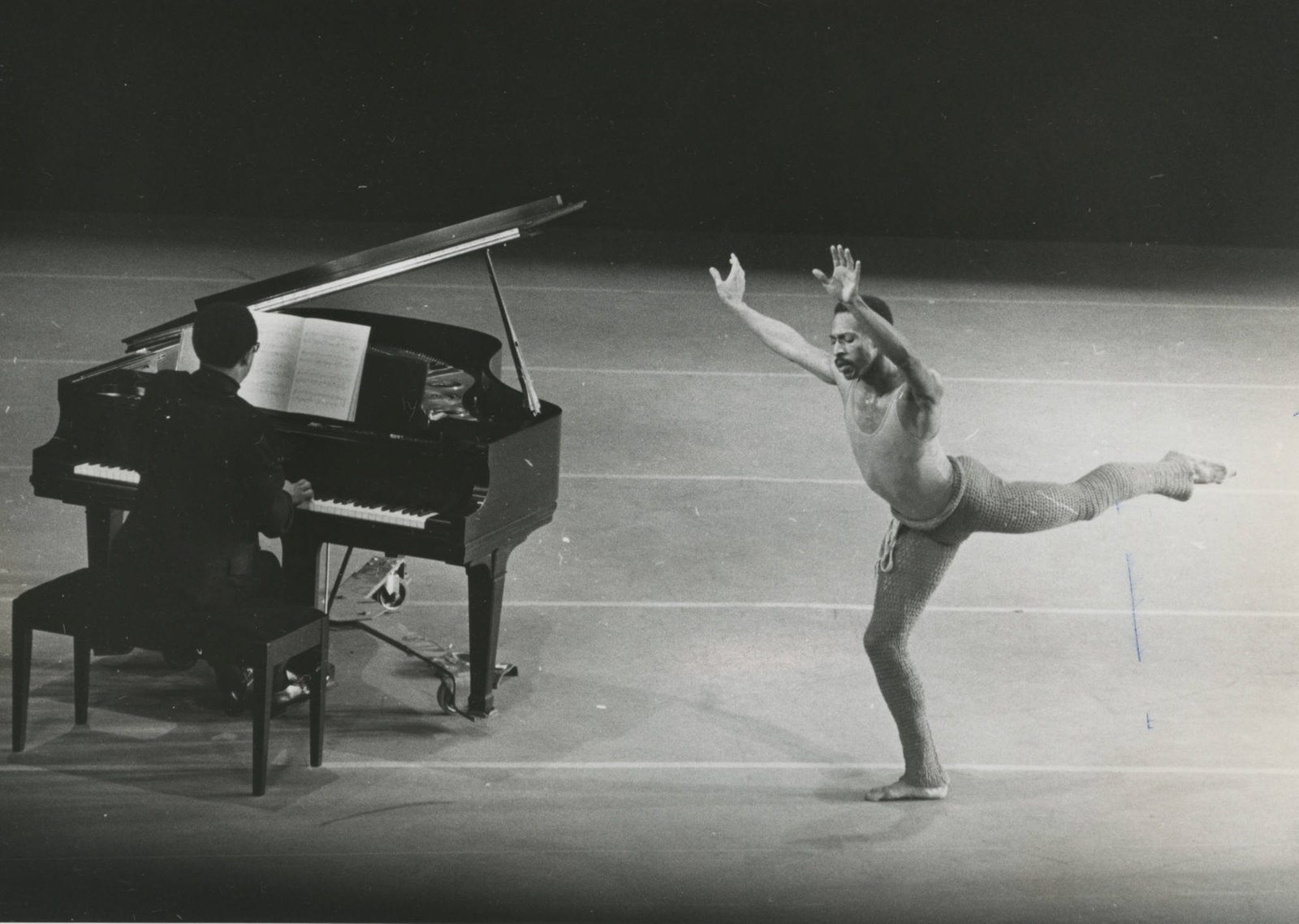

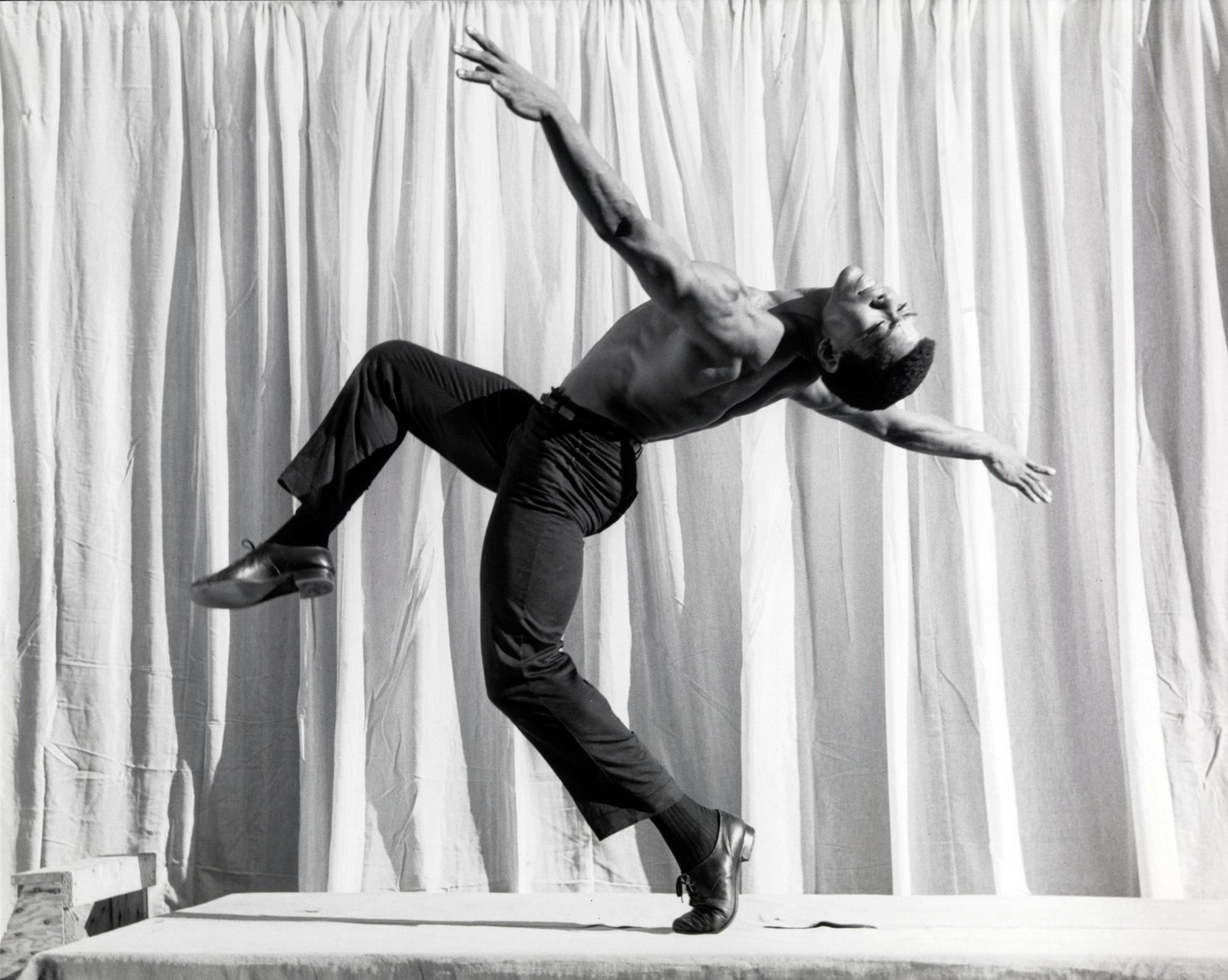

Fred Fehl, Dudley Williams in Gymnopedies, Spring 1971. Photograph, 5 x 7 in. (12.7 x 17.78 cm). Fred Fehl Dance Collection. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin. © The Harry Ransom Center

Curating is space-making practice, and to mount this three-part, immersive exhibition, Dr. Edwards combined both the analytical approach she learned as a scholar and her lifelong relationship to dance as an embodied and sensual physical experience. She calls the show a “constellatory survey,” connecting disparate, glimmering aspects of Ailey's vast world.

What follows is a conversation about the broader significance of Mr. Ailey's practice, and the cultural implications of mounting such a monumental show in this time, at a historical institution like the Whitney Museum.Yaniya Lee: You spent 6 years putting this exhibition together. Part of your research was spent immersed in Ailey's archive, looking at documents from his personal and professional life, in which you noticed no distinction between his personal life and his creative life. Can you describe what made Ailey such a unique figure?

Adrienne Edwards: The word that I keep coming back to is curious. It's very easy to pick a way in which you want to work or a method that you want to work in, or an idea or set of ideas that you want to work through. I think I expected a certain linearity, but I was really surprised that it wasn't like that at all. Another word that comes to my mind is constellatory. He was a big fan of lists and taxonomies. Looking at his lists, you'd be like: Wow, why does that thing sit next to that? You could almost see him thinking in these bursts, a little like shooting stars or stardust. We will truly never know the connective tissue between these things. And we can't pick up the phone and talk to him and find out what he was thinking about.

YL: He was an artist, using his practice and experimenting with form to work through his ideas.

AE: And like any truly amazing artist, he was not driven by success. He was driven by this curiosity, and he was driven by a generous desire to support others. I feel like that's really unique. There was a real ethics to the way that Ailey worked. He was incredibly thoughtful, incredibly curious. I think he loved the dancers maybe more than he even loved the stage, or performing the dances. It was this relationality of his body in relationship with their body and what they could do together that was joyful for him.

Alvin Ailey. Photo by John Lindquist. © Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

YL: Was there something in particular he was trying to say with his work?

AE: A lot of people question whether or not the work was political. I feel like that expectation is always put upon Black artists. The representation needs to be clear and the aims need to be clear or your stakes are questioned. Or, if you're not articulating a very specific political aim, you don't have stakes at all. I remember finding this quote where he said: "If I'm on stage, it's political." I think that says it all. Looking at his diaries in particular, I do think he was asking very rigorous questions about why he was making what he was making, and also how it was being received. He was hyper-aware of the context in which the work was arriving. And even with his questioning, he pursued the work nonetheless.

The way that gay nightclubs influenced him. It was the sacred and the profane.

YL: Ailey had an appreciation of all different kinds of art, including dance and poetry and literature. He would even push his dancers to go visit museums. As you were working with his archive and the two repertory companies, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and Ailey II, to imagine a show for the Whitney Museum, what did you discover about the relationship between dance and contemporary art?

AE: At the time, dancers and contemporary artists were intertwined, in a way. They socialized together. They collaborated together. They were part of an aesthetic sensibility at that time, at the intersection of dance and minimalism and conceptual art. Artists like Jasper Johns and Rauschenberg are certainly also deeply related to that. With someone like Ailey, I found these unusual collaborations. So you have something that might be expected, like Romare Bearden, but then you have the amazing Puerto Rican designers who he partnered with to do the costumes for Studio 54's opening night. Or his relationship with James Baldwin [a longtime friend] or Langston Hughes [who inspired some of Ailey’s ballets].

YL: So in many ways Ailey enacted a broadness in his collaborations, and an interdisciplinarity within the practice of dance.

AE: Totally. Before it was something that became articulated by institutions as “interdisciplinarity,” Ailey was already in that mode. What I find really interesting is his faith in people's ability to understand that Blackness could hold all of these references. I think he questioned that fundamentally. So he told us that, yes, it's about the Black American experience. But then you look at what he's referencing, what he's reading, what he's looking at, and you hear the quote, which is in a video montage in the show, where he says: "And Black is universal. It's Black and it's universal." He really believed that. I think that he just knew that not everybody else would believe it. It was a kind of true imaginary that just got folded all together. The literary sources who he was looking at to build character, like Hart Crane, Tennessee Williams, TS Elliott, and Langston Hughes. The way that gay nightclubs influenced him. It was the sacred and the profane. You could sit there on a Friday night at the performance at City Center and you could have a great time and have no idea all these things were deeply embedded in the work. It's almost like the dances were veneers: they presented you one thing, but they were much more multivalent. The South for him was not just the American South, it was also Brazil. It was Haiti. It was the West Coast.

Fred Fehl, Hidden Rites, 1973. Photograph, 5 x 7 in. (12.7 x 17.78 cm). Fred Fehl Dance Collection. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin. © The Harry Ransom Center

YL: It's the first time this attention has been paid to Ailey's work in an institution like the Whitney Museum. In many ways, you're placing him in the canon of art history. Not that he wasn't already there in his own right. What is your responsibility as you canonize him and make him into this larger-than-life person for the exhibition?

AE: Well, in some ways Ailey was perfect for something of this scale. If you want to think about the sheer size of the space, or the sheer number of performances that are happening as part of the exhibition and alongside it.

YL: I guess I mean the cultural reverberation. What will happen to Ailey as a result of this show? Will it be like what happened to Basquiat?

AE: It's different because you can't commodify Ailey in the same way that you can a Basquiat. At best all you can do is support the company. You can support them financially. You can buy tickets and go see their work. But it's not like there is this dance that's for sale. Ailey is the perfect person for this because he's already an icon, and has been for so long. People already know the Company. And so it really becomes about focusing on him. And I think the very reason his legacy can't be monetized––which is not to say it can't be instrumentalized—is that it is about work that is ephemeral. This is probably the reason why someone like him hasn't already been shown in a context like this.

YL: I want to talk about the role of the Black curator. We've seen a major shift in the past couple of decades, especially in the last one, in how our institutions welcome and display Black art. As a Black curator, how have you lived this shift? What do you see your role is during this time?

AE: It's funny, I feel like I'm so in the doing of the work that I actually… I almost have these moments where I raise my head a little bit and I think about these kinds of questions you're asking and then I freak out and I just go right back into the work. I would just say it's incredibly complicated. I try to be as generous as I can be with the people who are alongside me or coming up after I did. That can happen in a lot of ways, but what I would say is that when I'm doing it best, they don't even realize it's happening. As I've gotten more senior in the context of museums, the thing that I also am probably most conscious of is that there are people who will always underestimate us. They can't see us coming, so they miss our arrival. And I often wonder how they're even able to receive the work. This is actually why I have to not really think about it. And so while I am hopeful and very happy about the ways in which so many Black people, particularly a lot of Black women, have come up into the field with real vision and are making incredible shows, and often in challenging circumstances, I do know the world out there is not always able to receive it. So our work is vitally important and doubly difficult. But you just flood it. You flood the world with shows like this and others, and you build yourself so that you can be made undeniable. If anything, I hope that a show like this can allow other people to receive 100% trust and 100% risk for their work, that those things need to come together.

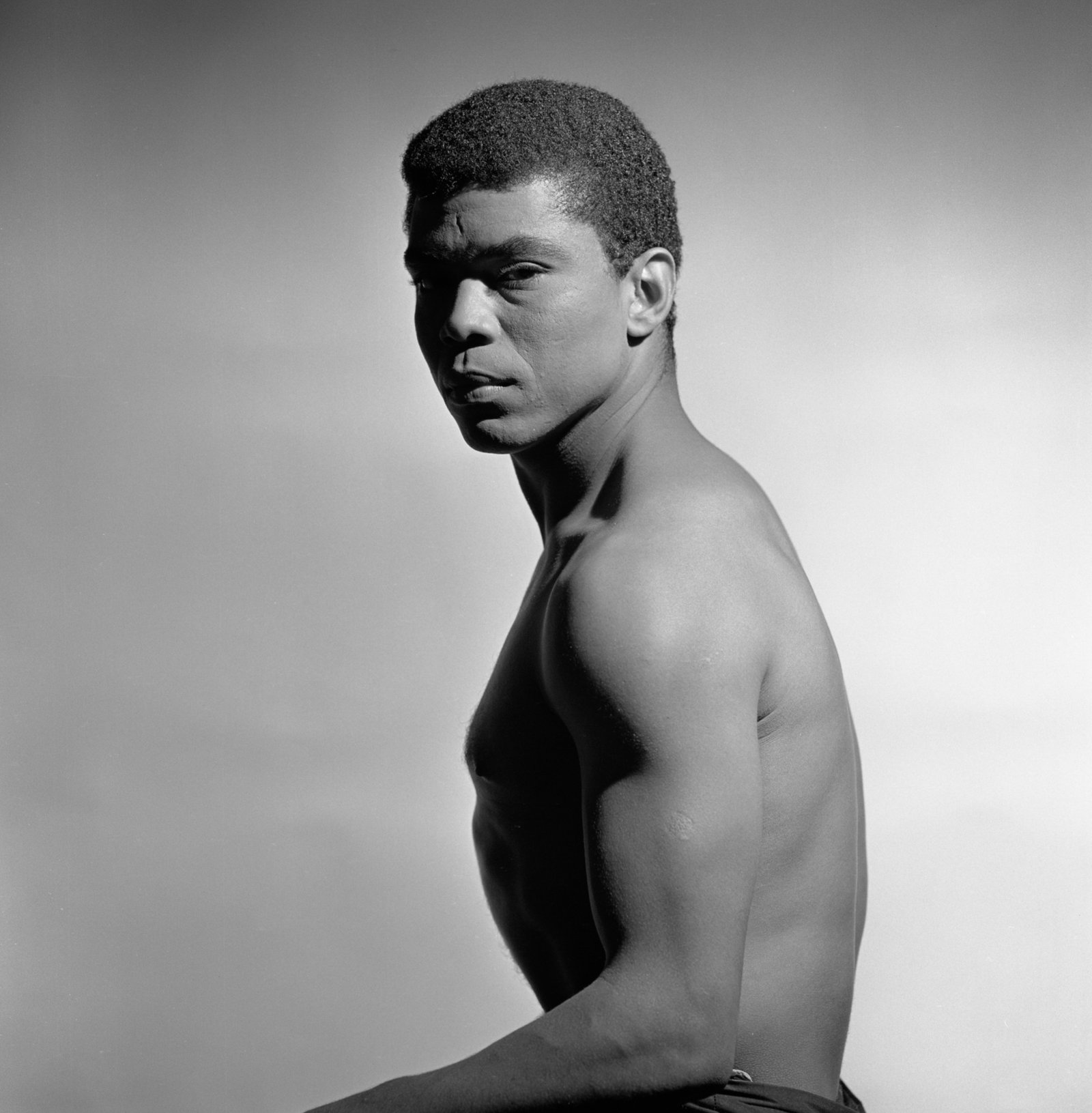

Jack Mitchell, Alvin Ailey, 1962. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture and Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. © Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. and Smithsonian Institution