Enter history class with Umar Rashid

Umar Rashid aka Frohawk Two Feathers carries his history everywhere he goes. The Los Angeles-based artist seen in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum, and MoMA PS1, reinterprets Colonial art to converse with younger generations about the histories of Black American life.

This story originally appears in Justsmile Issue 2, Together in the Fold.

Photography Shane J. Smith

Text Teri Henderson

Umar Rashid photographed in Los Angeles by Shane J. Smith.

Umar Rashid describes his work as a re-telling of histories. He’s a self-taught painter, and avid researcher, with a penchant for offering visual remixes of dark stories. His work is modern and ancient, humorous and macabre and deals with the inevitable aspect of Black life, that we carry our history in our present, into our future.

When I interviewed Mr. Rashid over Zoom, we laughed a lot, but also shared serious moments. This aspect of our interview is also a tenet of his practice. Although Rashid is currently in Los Angeles, he carries the legacies of his upbringing in Chicago, wherever he goes. Rashid is a sartorial artist as well as a storyteller; when we spoke, he wore a stylish white hat that I didn’t get the chance to ask him about, but I recognized from other interviews that he has a flair for headwear. We also talked about how Southern Chicago can be, which is similar to how Southern Baltimore is. This is the legacy of the transatlantic slave trade and subsequent great migration.

Rashid is a true multihyphenate, in a world where the term is often overused. He is a writer, poet, rapper, father, painter and an artist with brilliant understanding of his own positionality and practice. Like the rhymes his mouth echoes, with his paintbrush he remixes the past and by doing so, properly reinserts Black people into the art history canon.

Photo by Shane J. Smith.

Teri Henderson: I know you’re in L.A. right now. But where are you from, where are your roots and where are your people from?

Umar Rashid: I'm from Chicago, Illinois. I grew up on the southside of Chicago. I was born and raisedthere.IleftwhenIwaseighteentogo to school, moved back briefly and then left for Los Angeles when I was twenty-four. My parents are also from Chicago, Illinois. So, I'm a third generation Chicagoan.

TH: I know your dad was a playwright. And you’re a Libra, we already talked about that. You also have a few ... not pseudonyms. But other monikers.

UR: Oh, I have a bunch. And also some aliases.

TH: When did those start? And why? And is it still going on?

UR: I'm a multidisciplinary artist. It started a long, long time ago. I started off writing, actually, when I was a kid. And then later on, after all the writing, then I did art, I was in theater and music. Growing up in the theater, I just had gotten used to the theatricality of existence. So, every time I did something that was different –like if I did music, or I did, you know, more writing, or I did graffiti – I would always change my name, as my style evolved. Or just as I was doing a new project, so when people would call me by that name, I knew exactly what they knew me for.

When people say ‘Frohawk,’ I know they know me from art. If they knew ‘Cyclone,’ I know that they knew me from being wasted on the street, playing an autoharp.

TH: I saw that on your Instagram!

Umar Rashid ‘We will allow you to keep the lesser half of the shit you think you own. Shango and Oya destroy an empty, outgoing slave ship while allowing a crimson corvette to deposit the trade goods for the fete at Belhaven Manor. Don’t fuck with the cosmic gods’, 2021.

UR: For a while I knew where everybody knew me from. And much like most Black people in the United States, we all have some distant Indigenous ancestry. That kind of informed the ‘Frohawk Two Feathers’ persona a little. I wasn't trying to claim like, ‘I'm this and I'm that.’ It was just something that I embraced. But then again, people were asking me to do shows, purely from an Indigenous perspective. So all this stuff started to pop off. I was like, let me recuse myself from this before it gets out of hand, because I didn't do it to be malicious.

I was just going with the flow from what I know of my ancestry. That’s not how I identify. I identify as a Black man. So, I just started using Umar Rashid, my birth name.

TH: Your government name.

UR: But then everybody thought I was an Arab dude. Everyone is always asking me what the origin of Umar Rashid is, and how Frohawk became Umar Rashid. Umar Rashid is on my birth certificate. It is my government name. Now, there is another name at the end of that government name, but I don't respect that at all. Because them is the same people that owned my family. So as far as I'm concerned ...

TH: That’s that on that. UR: Yeah, that's who I am.

Photo by Shane J. Smith.

"I would say I was a political activist as much as a Libra can be".

TH: Thank you. Thank you. So, your rap moniker was Hi-Fidel?

UR: I was a bigtime supporter of the revolution. I was with the All-African People's Party that Kwame Ture had started. I would say I was a political activist as much as a Libra can be. At that time, I was young enough where I was like literally a card- carrying member of the All-African People’s Party.

TH: Was this in L.A. or when you were still in Chicago?

UR: I was in school in Carbondale, Illinois, which is about five hours south of Chicago. It was that point in my life where I felt that socialism was gonna save us all. I did research and that later informed a lot of what I do in terms of the stories that I'm telling now about colonialism, because I learned so much about Africa around that time.

You know, as a kid, I didn’t always see us. I didn't see myself. Where are we at in history?

‘Oh, there I am!’ Lugging like a bale or tobacco or cotton, eating some hog maws at a burnout outhouse church. Talking about, ‘We gon’ overcome.’ So I was like, ‘Why is it always like this?’ I grew up kind of ‘wokeish’ because of my parents. I thought, ‘Well I can do this too.’

So, the Hi Fidelity moniker came out of that.

UR raps: ‘The grand excelsior, unstable like molecules in Alka-Seltzer, scripts the Hi- Fidelita, communist, cult fiction, like Helter Skelter. My diction should be described as the livest techno-wizardry. So, I suggest you don’t try this. Praise the most high for what’s been given me.’ You know, I was out there!

TH: You were rapping rapping.

UR: Technically I’m still rapping. I can’t deal with the mumbles lyrics

TH: So, no Migos?

UR: How do you listen to a song that all sounds the same? Back in the day you had Pete Rock with the horns and Premier with the scratches; everything had a signature; emcees had a style. Now it’s like listening to a metronome.

"Chicago's in my blood, so Chicago goes with me wherever I go".

TH: I know you're from Chicago, you live in Los Angeles. I love Kanye. I know that's another side conversation we can have. But I love your Bound 6: The gym was on fire, but there's always time for toasts. I appreciated the Kanye reference. So, can you tell me a little bit about that painting? And are there any other places that Chicago references show up in your work?

UR: First I can talk about the ‘Bound’ paintings. I just finished Bound 15. The first ‘Bound’ I did was years ago.

Let me tell you about Chicago. I do have a narrative for Chicago. But I haven't made it yet, because no one's given me a show in Chicago. I'm very adamant about getting the show in my own city. My mom even moved to Atlanta, but you know, before I even got to show there, I'm still waiting on it.

But I did model some characters after Jean Baptiste Pointe DuSable, the Black Haitian man who founded Chicago. I have a narrative and I've included this particular character and a lot of the narratives. Chicago is in my blood so everything I do is Chicago, you know. That's my heart.

My friend colloquially called Chicago ‘Mississippi with tall buildings’ because we are pretty country – we real country out there. Chicago's a weird city because everybody literally is two or three generations removed from living in The South. People say hi to everybody, right before they run up on you and gun you down.

TH: Y’all have manners.

UR: Chicago's in my blood, so Chicago goes with me wherever I go. I rep Chicago to the day that I expire and turn to vapor. But the ‘Bound’ series ... he's a year younger than me, so I consider Kanye in some ways a contemporary, cuz he was coming up in the beat scene when I was young.

The ‘Bound’ series came out when Kanye met Kim Kardashian and they did that video.

TH: Yes, with the motorbike.

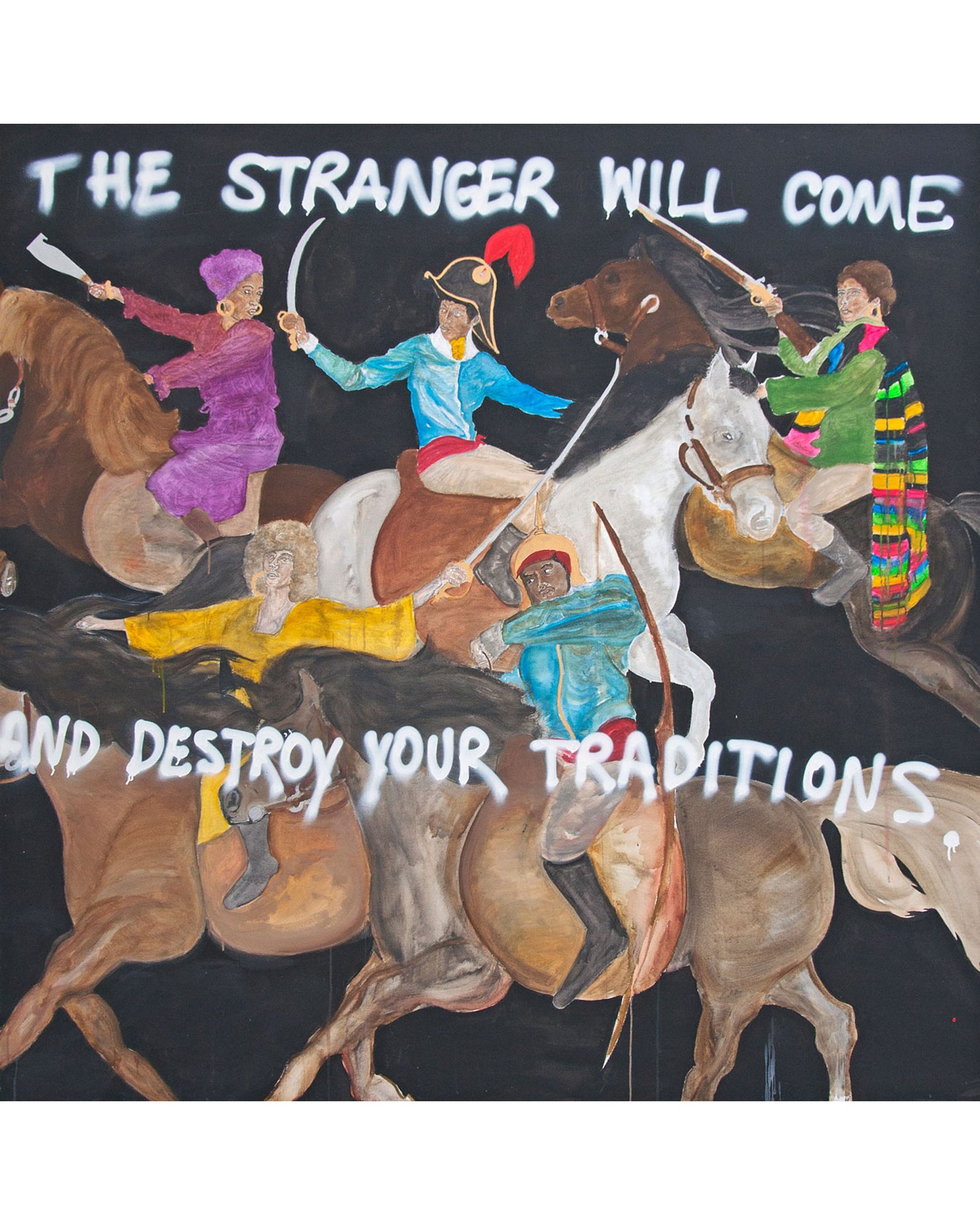

Umar Rashid ‘Etranger’, 2017.

UR: I did a show in South Africa [at Capetown’s Whatiftheworld Gallery]. It was dudes on horses, black dudes on horses in one of my battle scenes. Then I just had a white girl riding on the horse with him. His song was called ‘Bound’ ...

TH: ‘Bound 2’

UR: So, I started from Bound 3, so now I’m on Bound 15. So, the whole ‘Bound’ story sometimes I get kind of overwhelmed with the narrative because of the subject matter I deal with. While I try to make it slightly humorous at times, I'm dealing with real colonialism, real actual events.

TH: So, all of the work is based on actual history?

UR: All the occurrences are real, but not in the timeframes. The situation is different. I restructured a lot of things. I started in 1658. And I go to 1880. 1658 is important, because that’s when Oliver Cromwell, who became the Lord Protector of the United Kingdom after the English Civil War, died.

And 1880 is when the Portuguese finally abolished slavery. That was officially the end, then after that you get the industrial era. I just work in that whole vein of the age of colonialism, the age of exploration, age of discovery ...

TH: Quote unquote.

UR: Fucking air quotes all day. It's a global narrative. I'll research it and sometimes I'll get some things wrong, but for the most part, I'm very thorough in my research. Every once in a while, I want to do something fun. The ‘Bound’ paintings just give me so much joy because they're really fun to make.

TH: They’re also fun to look at. They made me laugh.

Photo by Shane J. Smith.

UR: Did you see the ‘Colonial Basketball’ series?

TH: Yes, I did. That was another one I really enjoyed.

UR: The ‘Colonial Basketball’ series, the ‘Bound’ series, and Anti colonialism in Four Easy Steps. There was a photoshoot that I did, they brought the solo cups. That was hilarious. I’ve been doing solo cups for so long; they’ve been in my work for ten years. It wasn't until this one Black dude came out of nowhere. I'm at the show. He's like, ‘Hey, man. They holding solo cups?’

I was like, ‘You the only person ever noticed that?’ He was like, ‘Man you a fool!’ People see it as just a regular colonial painting. I started out with painting face tattoos, now everybody's got face tattoos, so I was like, find something else.

I'm a self-taught painter. So, I evolve and evolve and evolve, but within myself. I’m taking my cues as things evolve naturally in the modern world. That gives me the tie-in, that I need to talk to this generation about the history that they should know, so also you know. [The work] is also like a learning, educational tool as well.

TH: I was also just looking at the Stockholm, Califas paintings that were at The Huntington.

UR: Stockholm syndrome. Ain’t nothing worse than a groveling negro, holding his dead white master – so when I did that I was like, ‘Look, I'm gonna get this chance to show my work at the Huntington,’ which is a very exclusive museum. So, I was like, ‘I'm gonna put this in here.’

That’s another thing that I don't shy away from either: I don’t shy away from Africans from the continent’s role in the slave trade. I don't shy away from the Arab role in the slave trade. I don’t shy away from complicity.

I'm trying to write a comparative re-telling of a historical narrative, where Black people are present and the instances where we were victorious and the times where we lose too.

There's so much history that is missing with us. Hopefully [my work] will inspire more historians to be less lazy with their research, with their writing of these new books for subsequent generations.

I have several modus operandi, if you will, for making this work. But first and foremost, it is for me.

Photo by Shane J. Smith.

TH: That was my next question: Why do you make the work?

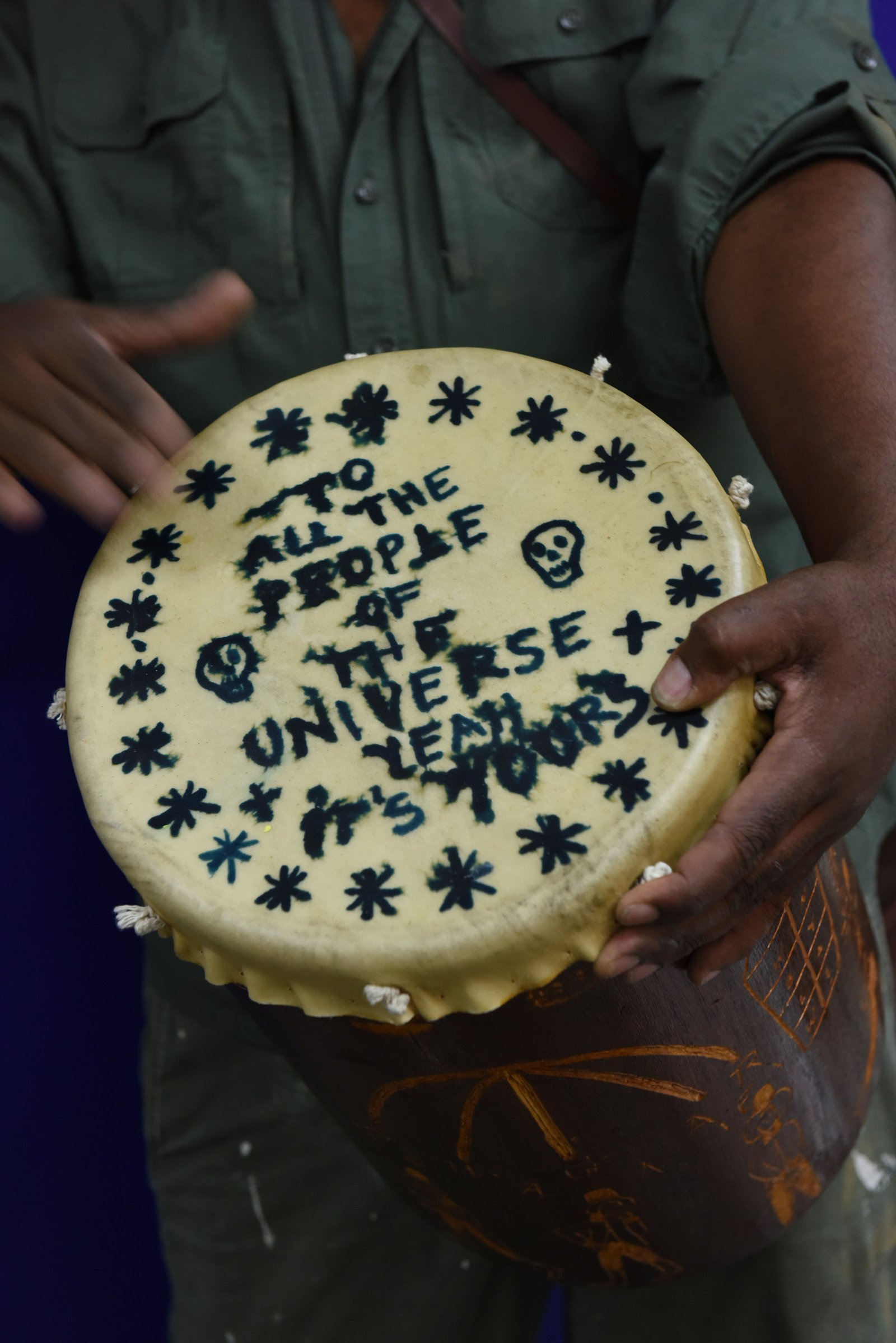

UR: It is for me. It is for all the people who've never felt like they were enough, or who never felt visible. It is to make the invisible visible. It is to tell a story in the hopes that we learn from it and don't forget. It's for the youth.It'sfortheold.It’sforthemiddleaged. It's for Chicago. And my mama and nem.

I felt, again, like I wasn't seen, and it's for the world, and it's for healing too. A lot of these stories that I've researched, people don't even know that they happened.

All of my students this year, I taught virtually.

TH: Where do you teach?

UR: At Claremont Graduate [University]. I taught virtually and my students said, ‘Umar we came back because you don't make it hard to understand. You say just do the job, do the work. Get it done.’ A lot of people are gonna want a lot of different things from you, you give them what you want to give them. You don't have to go to all the parties or go kiss anybody's ass.

TH: That’s good advice.

UR: Just make the work. And make sure that work you’re making is important to you.