Tremaine Emory on life & death, friendships & family, artifice & authenticity

This story appears in Justsmile Issue 3, Reflections are Protections.

Photography Jesse Gouveia

Sittings Editor Kevin Hunter

Text Rahim Attarzadeh

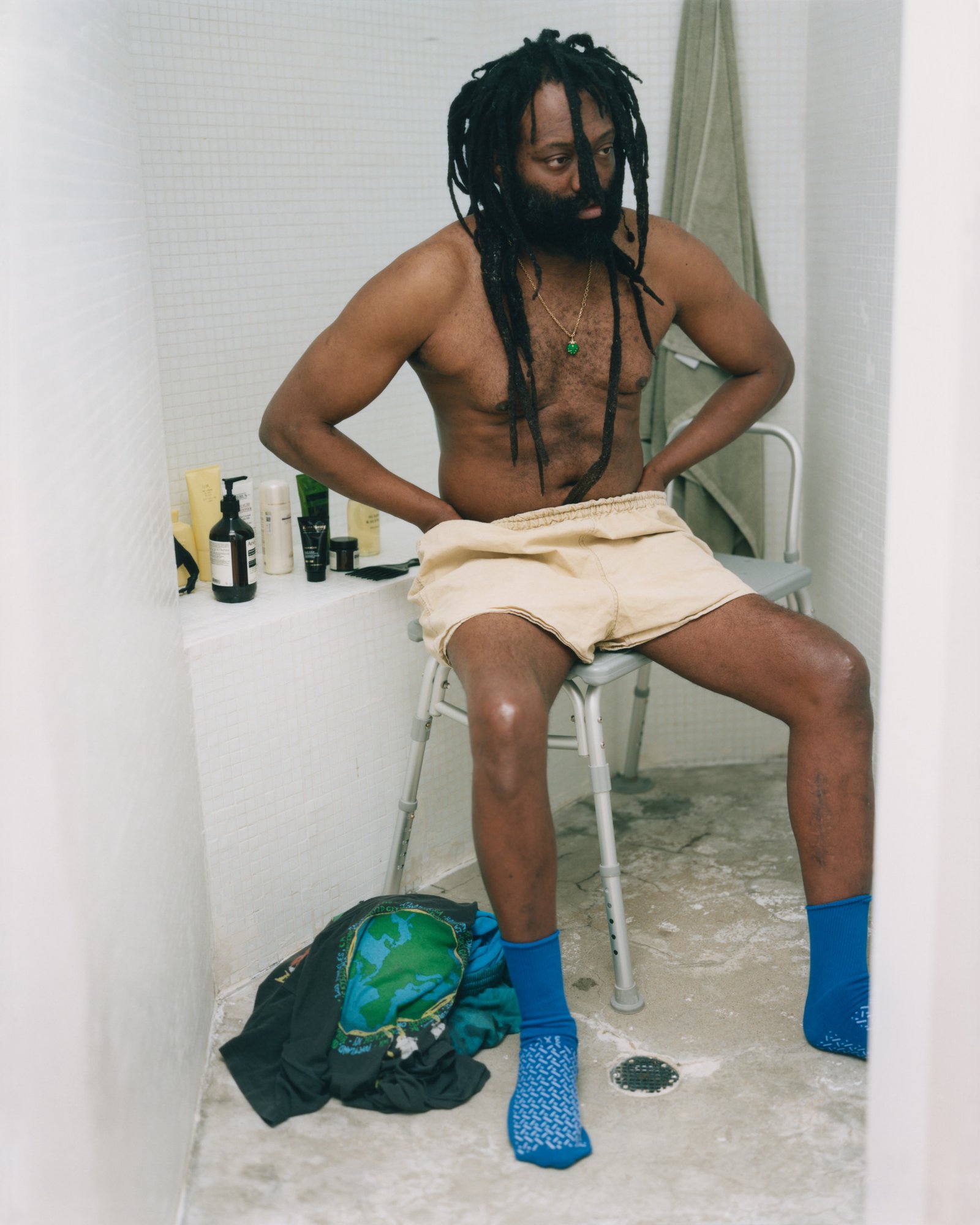

Tremaine photographed at home his home in New York.

In the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute in New York, lies an ambitious overview of American fashion, from Claire McCardell to Ralph Lauren to Marc Jacobs. Among these sartorial artifacts devoted to the grand, defining designers of the past eight decades, stands three outfits by Tremaine Emory, founder of Denim Tears and forty-two-year-old-designer, visionary agent provocateur and multitalented creative.

Emory’s triptych contribution to posterity includes the Tyson Beckford Sweater, 2021 (named after the first African-American male model to gain supermodel status), artist David Hammons’ African-American Flag, 1990. The fabled Levi’s cotton wreath denim Ensemble, 2020 – in honor of his grandmothers, who once picked the cotton fields of Harlem, Georgia. And finally, the Tasman Onia, 2022 Ugg slippers, which reveal the uncanny correspondence between Emory and his Black Seminole heritage. The elements of iconography within the collection gracefully and meticulously stitch canvas to clothing, which skillfully translate the sensorial and stratified nuances of Emory’s technique from conception to creation.

Deeply rooted in the African diaspora and his Jamaica, Queens heritage, Emory creates work that evokes an off-kilter reality, indexing America’s harrowed history starting from when the first slaves arrived in Virginia in 1619 and captured through an unretouched, polaroid haze that makes Denim Tears his chronicled tapestry of historical and subcultural influences. It’s his distinctive vision, tapping into a collective unconscious born of Africa, his own family’s history of cotton-picking and a flair for iconography that birthed his Afro-Americana aesthetic — becoming a vivid tribute to twentieth century United States soft power, mapped onto a bold, yet flawed view of Black America (think James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time (1992) and No Name In The Street (1972)). The result is an accomplished framework of African-American desirability spinning yarns of denim, embroideries, knitwear, patch-working and prints, which can now be seen as a benchmark of how to approach and make a success out of a brand – that transcends the sometimes gratuitous and unfulfilling obstacles of fashion.

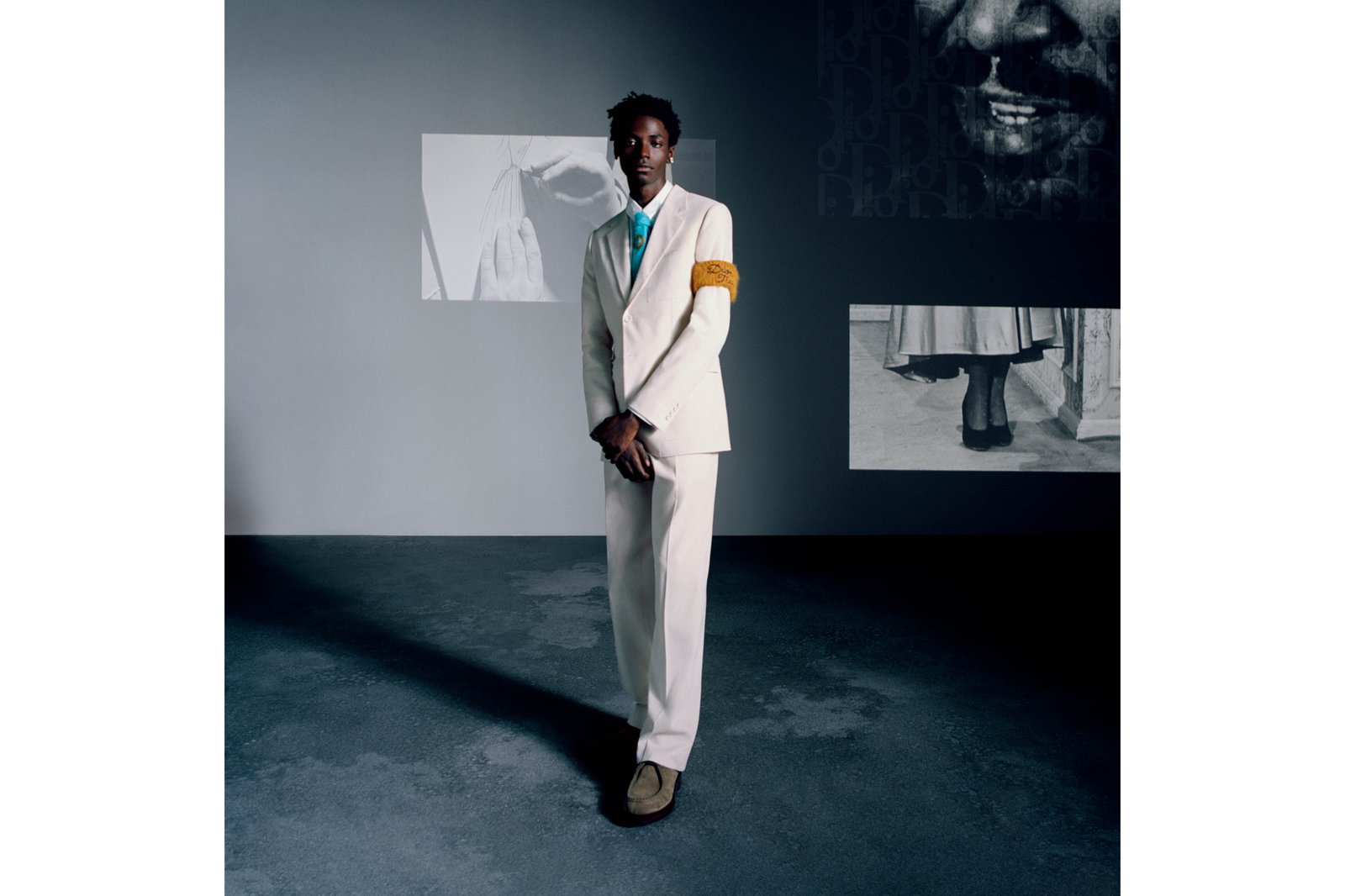

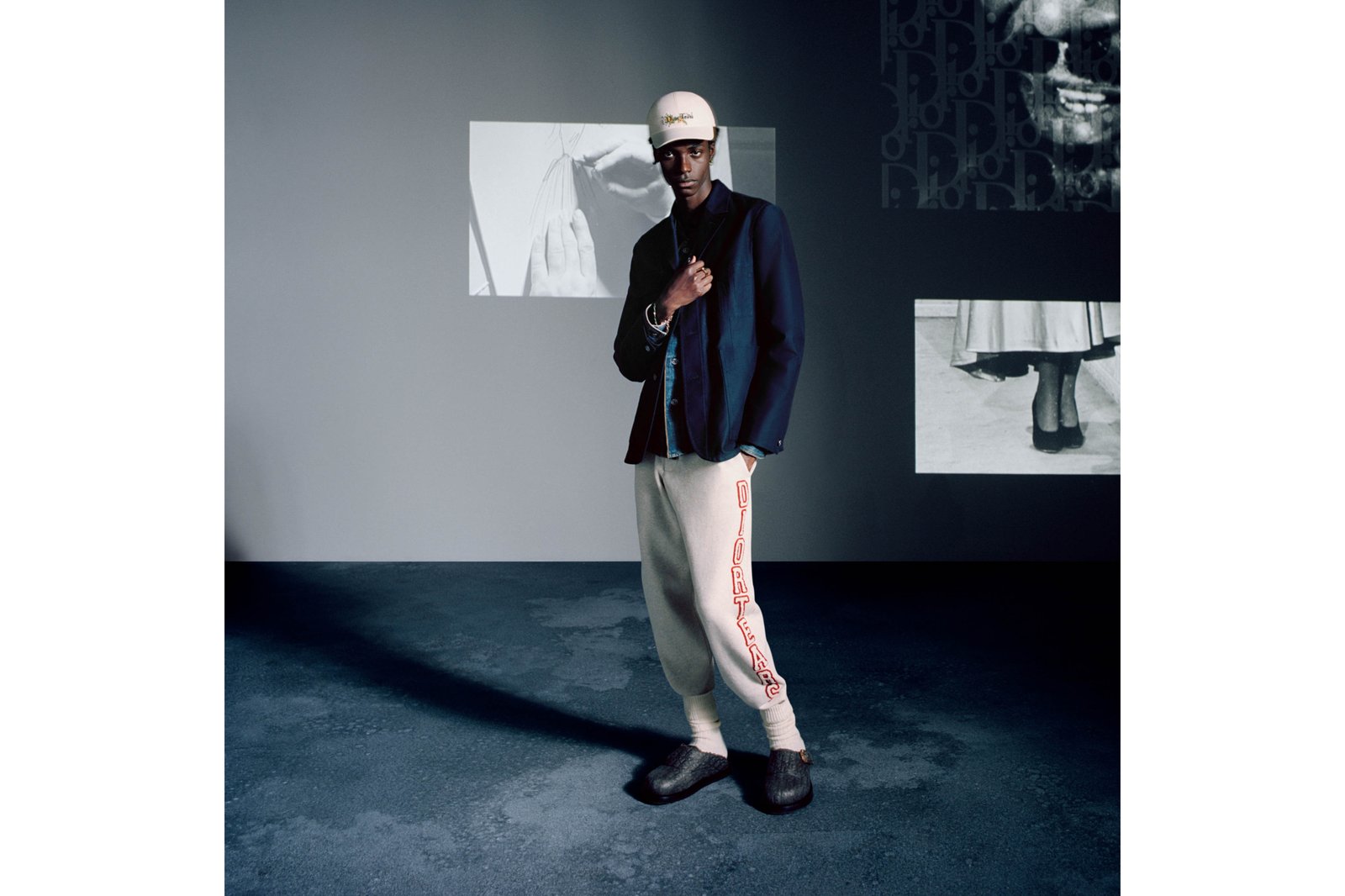

The story of Emory’s career is as adroit as it is astute: from the Marc Jacobs stockroom to the Dior showroom, whilst assembling a momentous string of collaborations, to becoming the first ever creative director of Supreme. When his work caught the eye of Kim Jones, artistic director of Dior Men’s, whose long–standing friendship transcends fashion and the influence its peripheral domains occupies, Emory began working with Jones in 2022 on the Dior Tears capsule collection. Together, Emory and Jones explored a rich visual lexicon of the aesthetic and cultural sensibilities between Black artists and creatives from New York to Paris, via New Orleans. The duo re-stitched negatives into narratives, splicing, scratching, constructing and reconstructing Jones’s honed inclinations of sharp tailoring and Paris high fashion with Denim Tears’ icons of design, accompanied by layers of photographic, artistic, written and musical references that manifested a collection infused of jazz, Rasta, workwear and Ivy League leisurewear.

The dialogue emanated through clothing, canvas and collaboration – manifests Emory as a kind of aesthete-cum-auteur: he designs the clothes, creates his own symbols, infuses dissident vignettes of music and literature, allowing for the multiple visions and interpretations of history.

‘I love Tremaine’s point of view about the taboo subject he’s coming with. He has a voice, he’s authentic, and that’s the reason why Denim Tears is so important. Doing something together was also an opportunity to have a larger audience thanks to Dior,’ reveals Kim Jones about his collaboration with Emory. ‘My friendship with Tremaine is an organic relationship. From the beginning of fashion, designers work with artists and artists work with designers. It goes hand in hand.’

In conversation, the deft storyteller, now part of the permanent collection in the Met’s Costume Institute, and the mind behind his denim delineation, talks life, death, innocence, authenticity and how a piece of cotton can equate a piece of history.

Rahim Attarzadeh: Your projects are so personal and intimate. How do you balance the juxtaposition between art and commerce? Do you think the two should be associated or divided?

Tremaine Emory: I live in the Western world, so art and commerce are indubitably linked. I don’t know. It’s a choice. Someone could make their art and not sell it. All of the things that I talk about are seldom told, in my opinion, and so the more the merrier.

RA: The more projects the better?

TE: The right projects.

RA: Since Denim Tears’ inception, considering all of these projects that you’ve undertaken, do you think the brand has a more unified vision now?

TE: Yeah. The codes of the brand are there. Even whilst I was out of commission, I was able to keep going because of that.

RA: How do you go about creating those codes? Can you talk me through the process?

TE: Your brand is like your village and you have a totem pole. When you enter the village, the totem has different iconography that explains the history, the soul, the ideology of the village or tribe. That’s what I endeavored to create with Denim Tears. Black Jesus with the cotton crown is one of those icons. The polo flips, 1619, the African flag, the peace symbol cotton wreath, the regular circle cotton wreath, the anarchy circle cotton wreath. There was a girl [Sinéad O’Connor] on Saturday Night Live ripping up the Pope and I changed it out and put a picture of white Jesus. Let's say that I would’ve died, images and iconography could’ve guided a successor to do their own thing that’s different but the same. That’s why I want to build a library of assets within Denim Tears that aren’t necessarily clothing, so that the story can go on with or without me.

‘If you seek their validation because so and so made you creative director, you’re losing. In fact, you’ve already lost. But if you seek validation, firstly, in yourself and secondly, in the community that you care about and who cares about you, you’ve got a chance to live a life without regrets.’

RA: After listening to your lecture earlier this year at Harvard, what advice would you give to kids all over the world to show them that they can break into creative industries, even if they’re not from conventional design backgrounds?

TE: I would want kids to know that you can do what you really love and with luck, hard work and support from your community, you can make it. How that pans out, I don’t know, I can’t say that you’re gonna become the creative director of Supreme or Louis Vuitton. I can say that you will be able to live a life that you won’t regret. I don’t know what treasures would be on your path, but you will live a life you won’t regret if you do those things and really just foster relationships with people you genuinely care about and who care about the same things that you care about. I would caution kids who care about the validation of these big conglomerates and media giants because these conglomerates are banks. LVMH is a bank. Kering Group is a bank. Paramount’s a bank. This is late-stage capitalism. These institutions will finance a designer, an artist, a band, a director, a writer or whatever to make something to get more money than what they put in. That’s what it’s about for them. So, if you seek their validation because so and so made you creative director, you’re losing. In fact, you’ve already lost. But if you seek validation, firstly, in yourself and secondly, in the community that you care about and who cares about you, you’ve got a chance to live a life without regrets. Not a perfect life and not a life without mistakes or flaws but a full life. You won’t be a perfect human, but a whole human with shades of gray. If I’m gonna be a role model, that’s what I’m kicking to kids. I’m not out here telling kids that you can be Virgil version two. You could be who you want to be if you have the courage to find out who you are.

RA: We’ve spoken about the growth of Denim Tears but what about you? Do you have a vision in mind for yourself? You’ve recently danced with death. I don’t want to pry too much about the gravity of this experience but how has it altered your way of thinking and how you want to be remembered?

TE: I remember my first day outside. I was still in hospital after my aneurysm, with a 5 percent chance of living. It was after an eight-hour surgery. I got to go outside whilst I was in the ICU and my man Chris Burrows flew in from London to come see me and sit at the bed and hold my hand and stay the night with me. He was there with me because I was struggling in and out of two medical comas and not just Chris, but my girlfriend, Andee she was there almost every night, and my friend Anthony Specter. My dad was there so I had a lot of support but Chris happened to be there, and they said: ‘Do you want to go outside? Do you think you can go outside? You need to get outside.’ I haven’t been outside in a month and I got all these tubes hooked up to me and they gotta unhook them all. The first time I sit up, they had to get me up because I couldn’t move my legs and they put me into a wheelchair. When I get outside, I see the sun and I realized this is the same sun that shined on the dinosaurs, that shined on the first single cell organism that came out the water, if you believe in all that. That shined on the slaves in the cotton fields, that shined on my grandmas who are no longer here. My nana, the sun shined on my mum, shined on the Incas, shined on every living being that’s ever lived on this earth. I had the same sun on me and in that moment, I was like: ‘Yo, this is everything and nothing’. Being in that moment was like being born again. Seeing the sun for the first time, when I never thought I’d see it again. I remember being in the ambulance on the way to the hospital, not knowing if I was going to make it…

Tremaine at home in New York. Brooch (on hat) and blanket DIOR TEARS. T-shirt, shorts and sneakers Tremaine's own.

RA: I would like to share an anecdote from a previous conversation we’ve had. You once told me that for you, a metric of your own success is that you’re now in a position where you can afford to catch a flight if a family member gets sick, or pay the hospital bill, or just be there. I’ll never forget that. I hope you had people around you when you were sick.

TE: I had Chris, Acyde, my buddy Frank [Ocean] but the protagonist is my partner Andee. She was by my side from the moment that I got sick to this day. She saved my life just as much as the doctors. I’m lucky, man. I just want to focus on gratefulness. I was in rehab and I saw the depths of pain that people go through. Prodigy has got a song called ‘You Can Never Feel My Pain’, it’s about Albert Johnson having the autoimmune disease, sickle cell. It’s one of my favorite songs ever written by any artist. Two verses where he raps about his experience of having sickle cell from childhood. Going through what I’ve gone through. I don’t understand what it feels like to have sickle cell but I understand what he means when he says: You can never feel my pain. I’m grateful to be living and I need to do things because there are people who are living who don’t have the opportunities to do things that I have. That doesn’t mean that I have to take every opportunity or that I owe anybody shit.

RA: Speaking of recent opportunities, let's talk about the recent Dior Tears collection. How did your collaboration with Kim Jones come about? Did you feel that there was a real sense of trust because of your longstanding friendship with Kim?

TE: We both decided that it was the right time to do something together. Dior had a slot for us to make a collection and we did it. We met through a mutual friend in New York in 2006. Kim and I are part of the same tribe. We understand the same smoke signals. We like similar things. There’s things that he likes that I learn about from him and vice versa. I think the main thing is that we both love knowledge. Kim has an incredible book collection, an incredible archive. He loves culture, traveling and what that does to you if you have the privilege of being able to travel.

Dior Tears collection photographed by Liz Johnson Artur.

RA: What do you find most interesting about Kim’s vision for Dior? He has managed to incorporate the iconic Christian Dior blueprint into the menswear, such as with the Bar Jacket and the Saddle Bag. He’s the most notable Dior menswear designer to hone in on these design elements.

TE: Good question! Shit. I would say tailoring and fabrics. There’s this mohair sweater that I was wearing and my friend was like, ‘Yo that’s fire, that’s Dior? That’s fucking crazy. That’s like Coogi.’ But back to the tailoring, Kim studied under Louise Wilson and then his appreciation of art and working at Bond International for Michael Kopelman. All that meshed in. He was also a club kid. He loved hanging out. He loves music. All that is thrown in a blender.

Dior Tears collection photographed by Liz Johnson Artur.

RA: It’s playing with the codes of tradition. I think that’s what you and Kim did successfully in that collection. You curated something that played with the codes and rewrote the history books but it still felt very different and contemporary at the same time.

TE: The designs … some of my style is overt but at the same time, it’s traditional. I live life and then I let that feeling guide the design. I’ll give you an example. There’s a tuxedo that has a leather boutonnière that’s in the look book. It’s a beautiful piece but that look comes from an interaction I had with André Leon Talley at Marc Jacobs’ wedding. For me, Denim Tears is an art practice, that’s how it started, even before the brand came out. I was making these cotton boutonnières and I wore one to that wedding and I kept an extra one in my pocket in case the one I was wearing broke. André stopped me and said: ‘Your cotton boutonnière is so beautiful.’ His mouth dropped. I didn’t even say thank you. I put my hand in my pocket, pulled out the spare and gave it to him. The way he held it and the look on his face said everything. It said all the fucking pain that he went through as a Black man who grew up in the South, moved to New York and then moved to Paris where they called him a fucking gorilla behind his back. All that pain and beauty was revealed when I gave him that boutonnière. That’s why I designed that piece, it was to honor that moment. I can’t put that anecdote on the back of a tuxedo jacket, but it’s there and only me and André knew that. Kim doesn’t even know that. That’s what goes into my designs. It’s these vignettes of life, of a book, of a film that I translate into clothing.

RA: Throughout the process of conception to execution, did you consider the fact that you would be giving the industry a history lesson?

TE: That’s just what I do with my team or my collaborators. Whether it’s the ‘Tupac Tears Legacy’ project, that’s a history lesson. Pac was like twenty-five when he died and his style became mythologized like Kurt Cobain. There was also him wanting to start his own record label and seeing a different side of him, besides that thug life talk and all that other shit. There was a whole other dimension to him. We synthesized that into a collection of clothing. If you’ve seen my book collection, a lot of it is out of the sociology and history sections of the bookstore. That’s my whole thing. It’s what me, Virgil and Acyde have been talking about for the last decade. Trojan horsing ideas and stories into popular western culture that aren’t normally there.

‘I have a question for Arthur [Jafa]: "What would Black people be like if we loved ourselves as much as we loved being loved by white America?"’

RA: I want to delve further into the African diaspora you seek to aestheticize through your creative practice. In Arthur Jafa’s film, Love is the Message, The Message is Death, the American actress, Amandla Stenberg posed the pertinent question: ‘What would America be like if we loved Black people as much as it loves Black culture?’ What’s your answer to that?

TE: I have a question for Arthur: ‘What would Black people be like if we loved ourselves as much as we loved being loved by white America?’ Black people aren’t a monolith, so I can’t speak for Black people and that’s what western culture in America does because there’s so few Black people that make it through the cracks of this white-male, capitalist society. When you make it through, whether you’re Tremaine or LeBron James, it’s a case of: ‘Well, you’re here now negro and you speak for all negros because you’re the only negro in the room. You’re the only negro doing the interview, in the Coke commercial, the fashion show, so you gotta speak for all negros.’ I can’t do that and I’m not gonna do that. My culture and my people are deeper than my thoughts. I’m just one human-being. I think you’re asking an amazing question but it ain’t happening. I would rather focus on what we’ve got to deal with and fight against. What if white people loved Black people as much as it loves Black culture? They fucking don’t, so I can’t waste my time thinking what if. It’s better to think about what we would do if we felt better about ourselves. Maybe we would get the fuck out of this country because this country don’t love us, so we all out. Think about the impact of Black culture and imagine Black people being like: ‘Yo, we out’. All 20-30 million of us. We out. Whether you’re a crackhead or LeBron James, we are out of this motherfucker. What’s America got then? So, that to me is the real question. What if Black people actually had solidarity? We’ve seen it in other cultures where people have solidarity and how they change how they’re viewed. What if Black people actually had solidarity? We don’t right now. We’re fragmented. Fragmented in Africa and fragmented here. There’s colonialism and systemic racism and then the consequence of that within our culture that we play out. It’s cause and effect on loop. It’s a great question and, perhaps, too painful to think about what America would be like if Black people were loved as much as Black culture. Do Black people love Black people as much as they love the idea of Black culture?

RA: So it’s a case of Stockholm syndrome? Do you see this fight against a system of oppression as a healthy ideology? Pushing barriers, can that still happen?

TE: Exactly. The government has made examples of Black folk, who totally don’t give a fuck about what white folk think of them and they’re called the Black Panthers. The government created this thing called COINTELPRO that destroyed the Black Panthers. I’m not judging because when you go full, like ‘Nah, I’m not having none of it,’ we’ve seen what happens. Whether it be Bobby Seale, Huey P. Newton, Fred Hampton, the whole Black Panther movement – Martin Luther King, Malcolm X. I’m saying the big names but there’s thousands of Black folk who have fought against this system and they’ve been punished in ways you can’t convey in this interview. I get the conundrum about giving a fuck about white validation. There’s great books about it. Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (1952).

Tremaine at home in New York. Brooch (on hat) and blanket DIOR TEARS. T-shirt, shorts and sneakers Tremaine's own.

RA: Would you say that this overarching need to feel acceptance has overpowered any potential for solidarity, when it comes to Black people living in America?

TE: Acyde sent me a song recently, ‘Black Boy Fly’ by Kendrick Lamar. The depth of that fucking song, because it’s about a young Black basketball player in the hood and his ascension, but also people trying to keep him back. The whole dynamic of being the superstar basketball player, that can make it out and what that causes in your community. It’s like, do you appreciate the fucking Black, female teacher in your neighborhood as much as you appreciate LeBron James? That’s what I’m talking about. Do we love Cornel West as much as we love LeBron James? Why do we give a fuck about musicians and athletes so much? They’re not even a fraction of the Black pool of genius but they’re the ones that are most heralded.

‘Do you appreciate the fucking Black, female teacher in your neighborhood as much as you appreciate LeBron James? That’s what I’m talking about. Do we love Cornel West as much as we love LeBron James? Why do we give a fuck about musicians and athletes so much?’

RA: Denim Tears represents this algorithm between your work and devotion to the human condition. Is this something that made you approach your own life in a different way, or is it just a wonderful parenthesis in that deep-time mode in which you work?

TE: The codes I set with Denim Tears, the codes Virgil has set, the codes Acyde has set are generational. Someone else can take the baton and do that shit because I’m a human being and I have a responsibility to myself and my partner and my family to enjoy life. My shit can’t be pushing the envelope to the point that I’ve got nothing left. I’ve done that. Flying around the world. Japan twice in one week. Fly to Paris for one day to work on this collection then back to New York to work on Supreme. L.A. for Denim Tears then fly to Paris the next week. I’ve done all that shit. It’s cool. I’m grateful but that shit ain’t all there is to life. Doing more, solidifying your fucking name. In the end, it’s like there’s some shit that happened 4000 years ago that didn’t make it into the books. Is it less important than the stuff that did? In the end it doesn’t fucking matter because you die, you’re not there anymore. I can’t only focus on the mission anymore. That’s for someone else to grab the torch and go for it.

RA: As we’ve been speaking, one thing I’ve noticed is this sense of contentment that you now feel in life. You know what your priorities are.

TE: I’ve always had it, man. That’s the thing that people don’t understand about me. If none of this stuff happened, I wouldn’t give a flying fuck, man. I was happy working at Marc Jacobs as a stock guy. I was fucking happy. I hung out with people I loved, had fun, went to museums, went to shows, I ate great food. My shit ain’t that different now. It’s different to some around me and how the world perceives me but for me it isn’t different. You know what’s different about my life? I get a lot more sleep now.

‘What’s the next accolade? A couple zeros added to your bank account? What’s the next thing? I’ve been to too many funerals and I’ve never heard anyone talk about someone’s bank account or awards...'

RA: So, you have no regrets?

TE: I don’t regret how hard I worked because there was no other way for me to do it. To come from where I come from. I didn’t know Central Saint Martins existed. I didn’t know what an art or creative director was. None of this shit. I was living in Jamaica, Queens. Coming out of the household that I came out with Andy Warhol books, James Baldwin books on the wall. I still didn’t know that the opportunities were available, so we had to work in awkward, extreme ways to cut through the bullshit and make it. Hopefully kids and guys and girls, all genders, races learned, listened to the podcasts, read the articles with Rahim and Justsmile Magazine and then they don’t have to do exactly what I had to. My life was easier than my grandma's life because I didn’t have to grow up around the Ku Klux Klan. It’s easier for the next generation and harder in different ways. At some point, you’ve got to stop. Hero’s journey, act three, you’ve found the knowledge, you’ve brought it back to your people and then you go and live your life. If you only seek treasure, what’s the next mission? What’s the next accolade? A couple zeros added to your bank account? What’s the next thing? I’ve been to too many funerals and I’ve never heard anyone talk about someone’s bank account or awards. Only thing you hear is how funny someone was, how nice someone was, how someone helped when no one else would. Life is about what you make of it and if the meaning you give to life is searching for holy grails, fuck man, to me that’s a rough life.