The Gospel of Omar Apollo

This story appears in Justsmile Issue 4,

There's Still So Much More.

Photography Tom Kneller

Styling Marcus Correa

Text Connor Garel

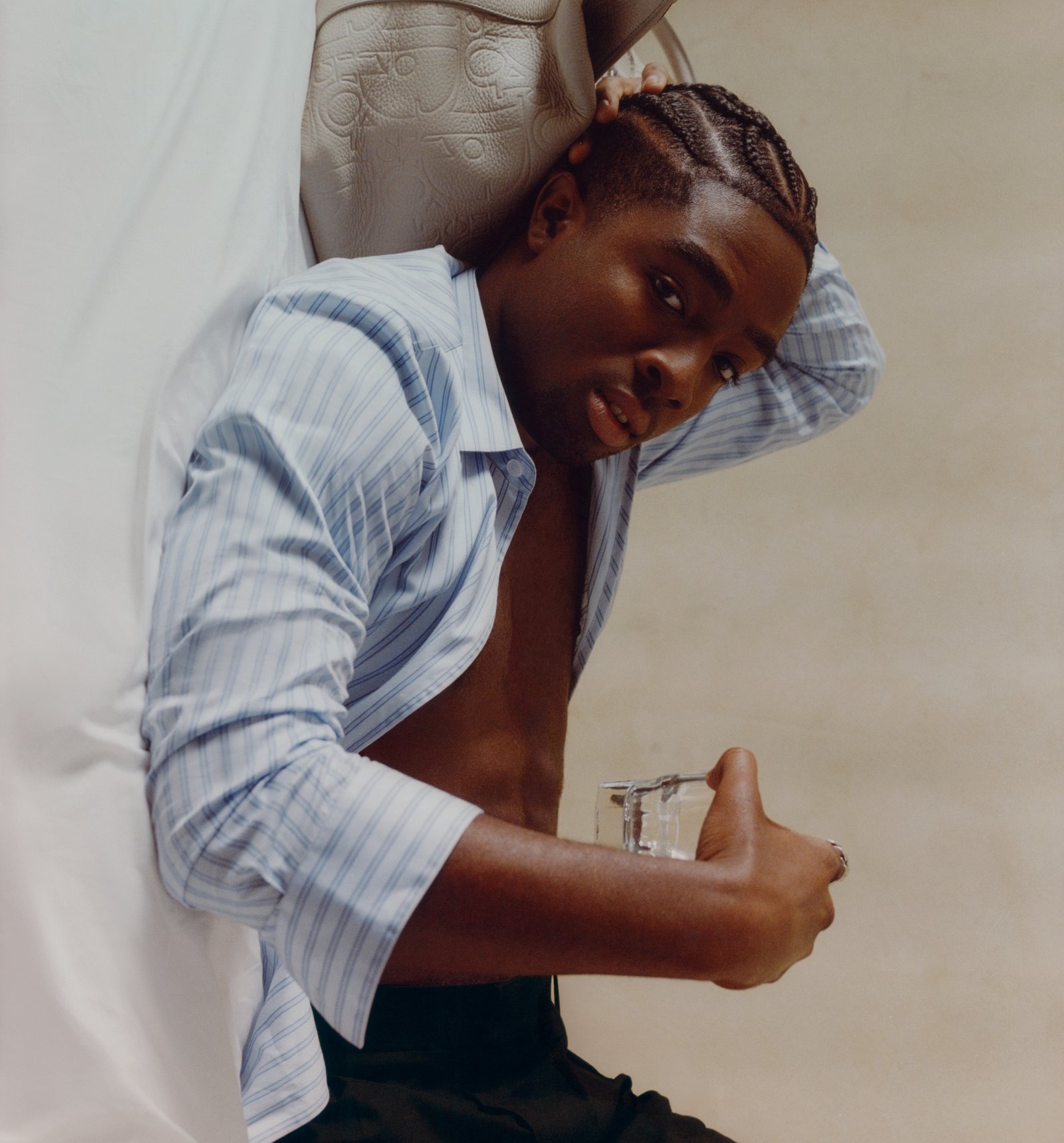

Omar wears shirt, jeans, and bag LOEWE. Bracelet TIFFANY & CO. Ring (right hand) TIFFANY & CO. Omar’s own ring (left hand) and earring.

Omar Apollo is sitting in his New York hotel room, hands clasped as though in prayer, talking about God and supposedly ungodly things. For the last several minutes, he’s been recounting aspects of his experience growing up in church back in Indiana, and we’ve now arrived at a brief aesthetic critique of Christian iconography, how the Renaissance men who painted ephebic saints seemed motivated less by reverence than by thinly-veiled sexual desire. “Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo – I mean, the Sistine Chapel is, like, super gay,” he says with a boyish smile. “Everyone’s naked, and it’s all men with perfect bodies.” Many Italian historians have claimed that the embracing men of The Last Judgment (1535-41) were, in fact, transcribed from the artist’s routine visits to gay bathhouses around Rome; an orgy, rendered by a certain hand, can easily resemble a religious tableau. “That would be so blasphemous of you to tell them,” he says with a laugh, miming the exasperation of the Vatican. But we agree that images of Saint Sebastian, which is one of Apollo’s many middle names, tend to conflate the sacred with the homoerotic: those eyes rolling back as arrows pierce his chiselled torso convey something more than physical torment.

I say all of this not to advance some undergraduate thesis on the sanctity of gay love and orgasms, or because the artist is a 6’5” heartthrob who writes primarily – in Spanish and in English – about the insurmountable anguish of love and lust, but because Apollo’s sophomore record, set to release in June, is called ‘God Said No’ (2024). It’s a title that emerged from a conversation with friends about the wisdom they were all raised on, which is that the course of our lives are predetermined by some all-seeing, all-knowing higher power, and that whatever losses or injuries you incur along the way were made for you and you alone. “It’s my take on how you just have to accept all the beauty with all the terror in your life,” he says. He considers it the best album he’s ever made, and while the pretty love songs he built his name on still abound, there’s a newfound anger here that flashes throughout, like light glancing off one inch of a sheathed blade. “There’s definitely a lot of romantic frustration on this album,” he says. “I’m like, gay people got all sorts of issues.” (Omar is in therapy, trying to straighten it all out.)

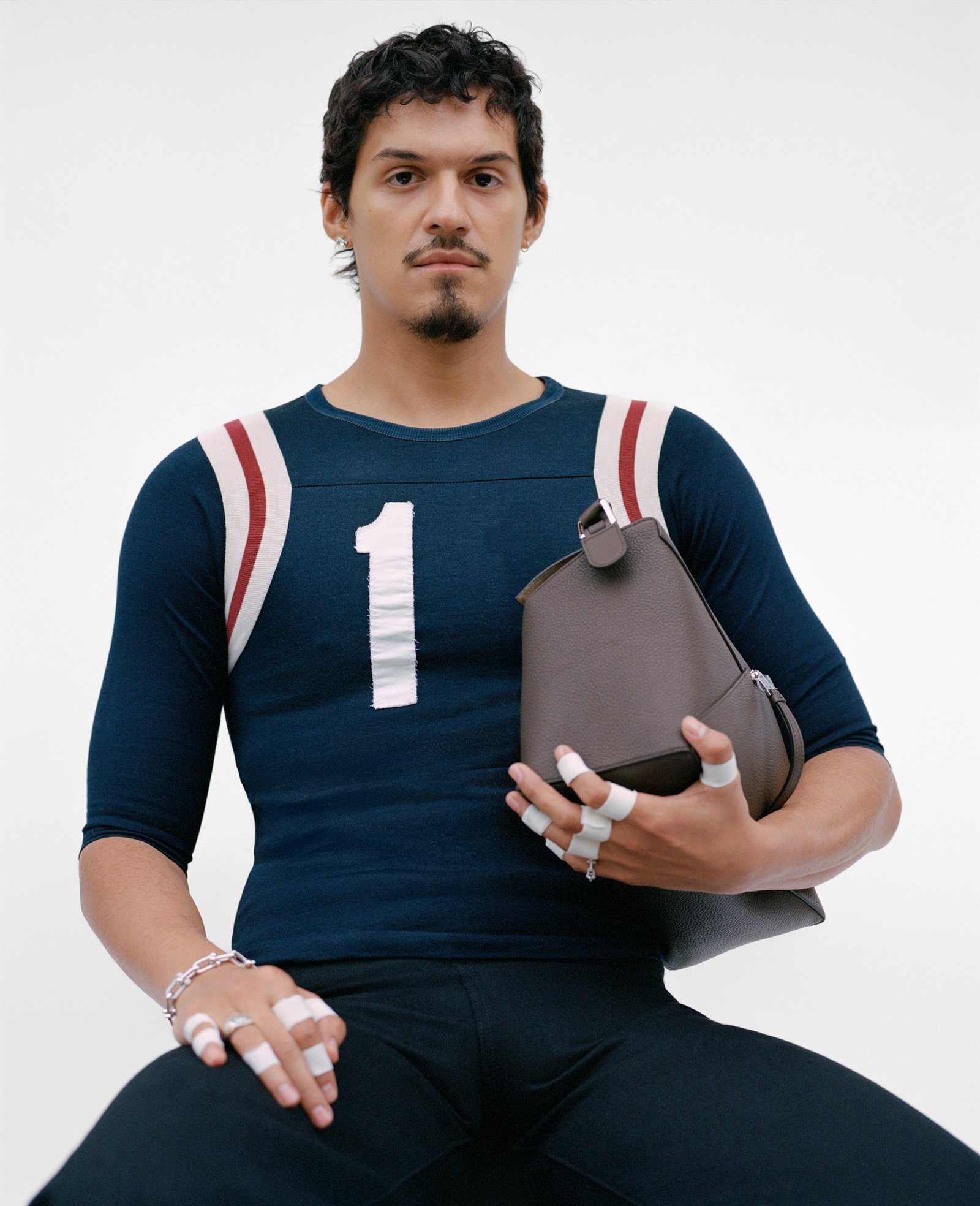

Shirt and tie DOLCE & GABBANA. Pants ISABEL MARANT. Shoes EMPORIO ARMANI. Necklace and rings TIFFANY & CO. Watch OMEGA.

Coming of age as an altar boy among priests and their paroxysmal sermons was one source of these unremitting “issues,” and it was their disapproving attitude towards queerness that initially caused Apollo to misplace his faith. He was raised by devout Christians who still forward him 45-minute prayers over WhatsApp – his mother, whom he brought to his first Grammys in 2023, does costume design for The Passion of the Christ plays – and so he spent much of his youth in church, where he also had his first kiss. He remembers sitting in hard pews and watching as the people around him shot up out of their seats with tears in their eyes and testified to the presence of something Big and Spiritual, something he could never get close to feeling, and when he finally did, after falling in love at 12 with an older guy who played guitar in the church choir, it was conveyed to him that this was neither Big nor Spiritual but instead Sinful and Immoral. He asked a priest about two girls he knew who had fallen in love, but the insufficient answer, which still reverberates in his mind, was that love between women or men wasn’t real. “I was just like, ‘well, that’s not good enough, I need somebody to elaborate a little more than that’,” he says. He still believes in God, and prays multiple times a day, but religion no longer brings him the same comforts that it used to. “I heard the Pope likes gays now,” he says with a laugh.

Apollo, dressed in a knitted polo sweater and oversized denim, is often playful in conversation, oscillating freely between youthful sarcasm and clear-eyed sincerity. He laughs often, and is especially good at conjuring the specifics of a distant memory – how it felt to be ignored by a first crush, the glazed look in a friend’s eyes while he strummed a guitar in church. It’s an emotional acuity that qualifies some of his best songwriting, like on ‘Evergreen (You Didn’t Deserve Me at All)’ (2022), the smouldering, John Mayer-esque heartbreak ballad that earned him a Best New Artist nomination at the 2023 Grammys: “He controls me/Was there something wrong with my body?” he croons over sweet guitar licks and drowned-out harmonies. “Am I not what you wanted?” He made ‘Evergreen’ with that friend from church, whose mother sent him there for reformational purposes after he was caught smoking weed; when he saw Omar playing a song by Metallica on the guitar, it solidified their kinship. “We’ve been friends ever since,” says Apollo.

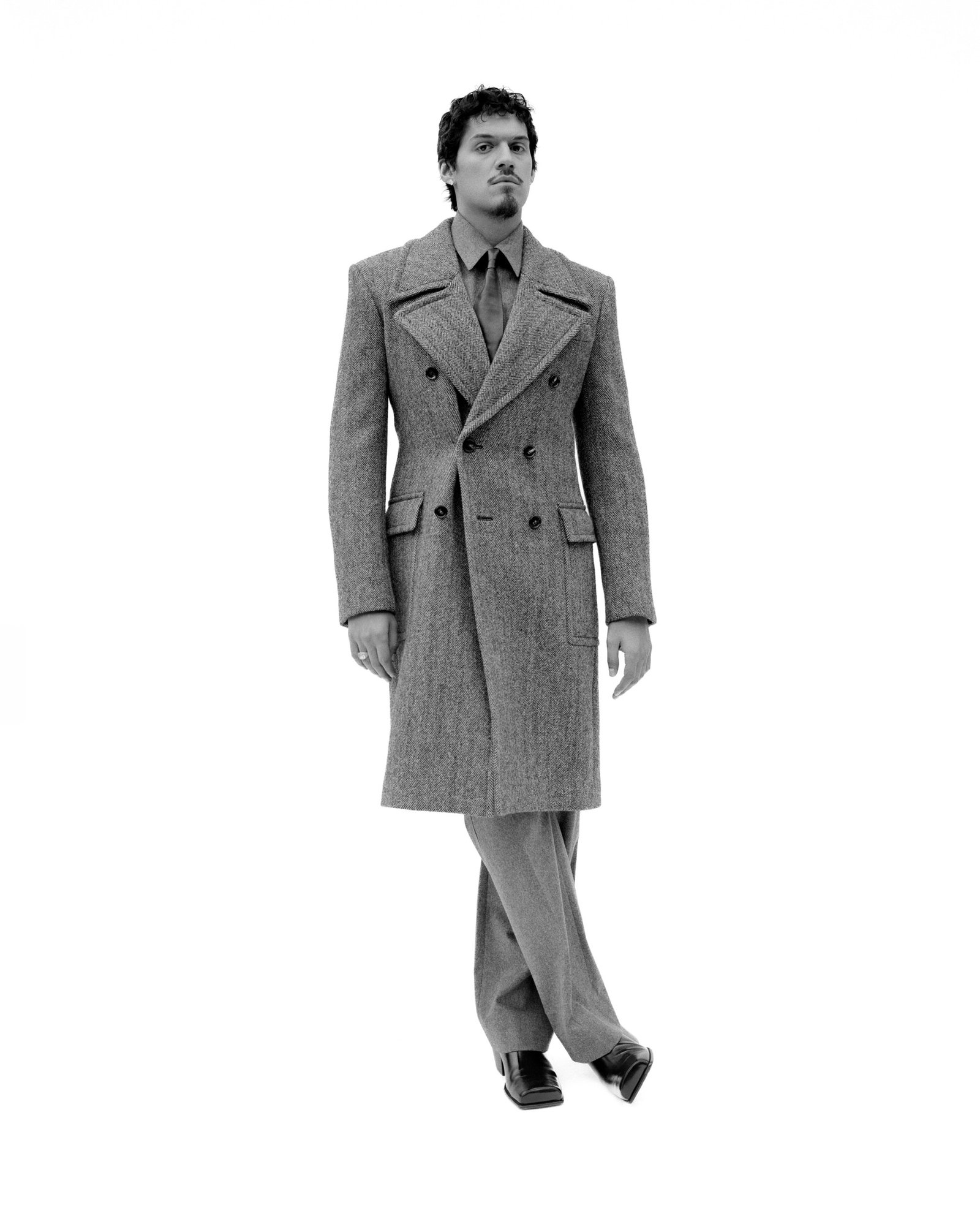

Coat, shirt, pants, tie and mules BOTTEGA VENETA.

That friend, Manuel, played bass in his band until recently. Most of his friends back then came from church, and because Hobart was so small, all cornfields and empty parking spots, they all lived down the street from one another, just a couple of minutes away on a skateboard. (After two broken arms and one concussion, he finally put the board down.) Hobart, half an hour from the town Michael Jackson grew up in, is not known for producing musicians. “I wouldn’t want you to go there,” he says. “It’s not that Indiana is terrible. But we just had so many stories from high school that are so wild that I cannot repeat them. There's nothing to do. And I think that boredom causes the violence – you know, fights and stuff, your friend murdering someone.” He never fought anyone, and jokes that he has too much money to fight anyone now, but in high school there were times when he came close, including once when some kids tried to jump him in the bathroom because their friend seemed to like Omar better than he liked them. “I would get called a fag in the hallways for posting dance videos, or whatever,” he says, again with that laughter. “I’d be like, ‘oh, yeah, have you seen them?’”

He started playing music when his parents gifted him a guitar at 12, but he didn’t really start singing until he was a high school senior, searching “how to sing” on YouTube and trying to teach himself vibrato in his garage, so nobody would hear his efforts. He worked a job at McDonald’s until he could save up enough money to buy a laptop and a microphone, and used them to record some of his first songs, over beats he pulled from YouTube-to-mp3 converters. Initially he started out rapping with his friends, their breath forming small clouds in the cold air of the garage in the wintertime, until he decided to hold auditions for a band. When he posted ‘Ugotme’ on SoundCloud, it racked up more likes than he’d ever seen. A friend CashApped him $30 to put it on Spotify, and the morning after he did, he awoke to find it had racked up 20,000 streams. He dropped out of college after two weeks to pursue music full time, and in 2018, he moved to Los Angeles for good.

Tank top, pants, loafers and belt AMIRI.

This new record, which he recorded over the course of ten months between London, New York and Los Angeles, exists on a similar plane of genre-agnosticism that made ‘Ivory’ (2022) such a step forward in Apollo’s musicianship, what with its casual pinballing between 2000s indie rock, Latin-infused trap and simmering Motown. The songs on ‘Stereo’ (2018), his first EP, were lo-fi, atmospheric R&B tracks he made in the attic bedroom he shared with four other roommates, back when he was working at Guitar Centre in Indiana and struggling to pay his rent. Cuts from ‘Friends’ (2019), the EP that followed, drew more heavily on the vintage soul, disco and psych-funk of the artists he grew up on, from Prince (who he evokes on the album art for ‘Apolonio’ [2020]), to Sly & the Family Stone (whose ‘Just Like a Baby’ is one of his favourite songs) to P-Funk’s Bootsy Collins, who remixed ‘Stayback’ ( a week after Apollo DMed him a heart. (“He’s the GOAT,” says Apollo. “I asked him how he made ‘What’s a Telephone Bill?,’ and he was just like, ‘I was just by the telephone booth, man, I used to call this girl all the time, I needed her.’”)

Jacket, shirt, pants, tie, belt DOLCE & GABBANA. Watch OMEGA.

‘God Said No,’ on the other hand, slots slow-burning acoustic guitar ballads (‘Be Careful With Me,’ ‘While You Can’) next to breezy, jazzy breakup anthems (‘Done With You’), a voice note from his friend Pedro Pascal about his “shattered heart” (‘Pedro’), and songs that feel telegraphed from a hazy discotheque in 1980s New York (‘Less of You’). He spent three months of last summer holed up in London with his longtime friend Teo Halm – who produced his last record and much of this one, with help from Carter Lang and Blake Slatkin – and all that drinking, partying and chain-smoking seeped into some of these songs, which mark the first time Apollo has played with dance music since 2019’s 80s dance-pop/disco track ‘So Good.’ “I’ve always had an interest in dance, funk, disco, whatever – I’ve always wanted to pursue that,” he says, “but it’s hard to tap into that dance vibe, because I feel like everything’s already been done.” ‘Drifting,’ with its driving four-on-the-floor beat, sounds like a formative car ride in a coming-of-age movie. The programmed drums, twinkling synths, and vocoder processing on ‘Less of You’ feel drawn straight from Giorgio Moroder’s adrenaline-fuelled playbook for the Midnight Express soundtrack, with its hypnotic, heavy-hearted electronica.

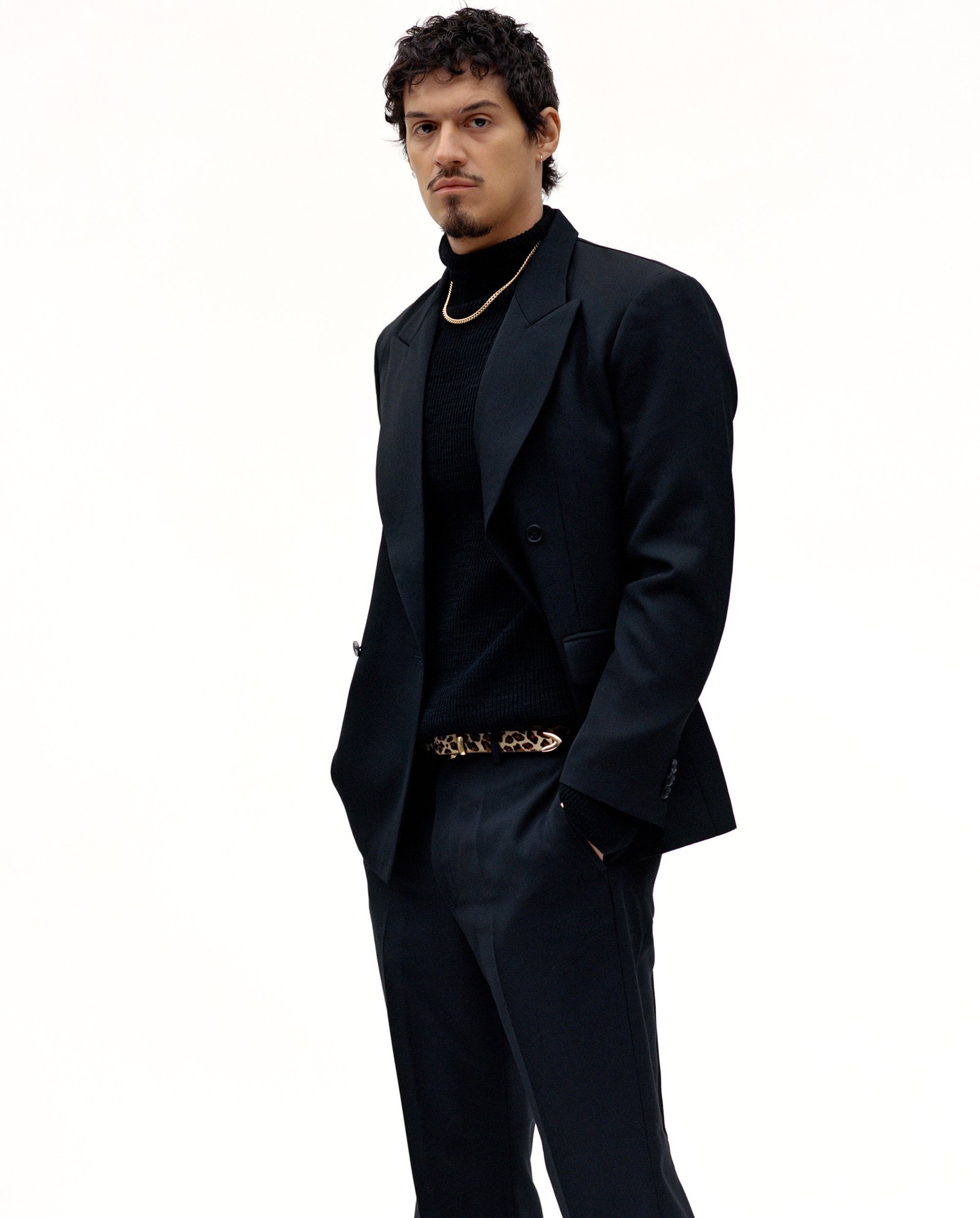

Blazer, pants and belt SECOND/LAYER. Turtleneck THE ROW from MR PORTER. Necklace stylist’s own.

He made the song during his first two weeks in London, when he was in love with a guy who was always listening to “computer music” and Apollo wanted to be the one in his ears. He’s the youngest child in his family; he craves unflagging attention. He often makes songs specifically for the people in his life, he says, songs that never see the light of day because he didn’t write them to be heard by the masses. “I feel like that’s just art, no? It’s your life that inspires it,” he says. “It’s like, you’re in my life, and you’re making me want to make something, so why wouldn’t I do that for you? All my friends are muses, I guess.” He only got good at playing the guitar, in fact, because he wanted to win the affections of that first crush, and recalls running away crying when he saw him sitting with his girlfriend at a bonfire in the church backyard.

‘It’s easy as fuck to write a song when you're heartbroken…’

The emotional tapestry of the album runs a wide gamut – yearning and regret, resignation and anger, arrogance and pettiness. ‘Spite,’ the album’s lead single, is about the discontents of a long-distance relationship where you can’t have your paramour all to yourself, and the desire to prove, by way of juvenile stunting, that you don’t really need them. ‘Against Me,’ similarly, offers some tossed-off bravado: “I cannot act like I’m average/You know that I am the baddest bitch.” When I ask whether Apollo finds it easier to write when he’s in love or when he’s heartbroken, it inspires a minor crisis. “Heartbroken, for sure – it’s easy as fuck to write a song when you're heartbroken,” he says at first, but then considers revising his answer as he sings the melody to Sade’s ‘I Couldn’t Love You More.’ “I don’t know – there are so many great in-love songs,” he says. He wrote ‘Glow,’ the album’s closer, and one of his favourite songs he’s ever made, while in love. But he can also recall a time when he was in love with a guy whom he couldn’t manage to write about because, paradoxically, despite their intimacy, he felt like he didn’t know him well enough. It wasn’t until the relationship had ended that he could see him clearly enough to sort it out, like when an image buried in an impressionist painting comes together with distance from the canvas. “I think maybe you just have more of a reason to write when you’re heartbroken,” he says, because it helps you to process the feeling, but then contradicts himself again.

Shirt, tank top and pants GIVENCHY. Hat and arm sleeve stylist’s own. Necklace, bracelets, and ring (right and left hand) TIFFANY & CO.

Someone knocks on the door of the hotel room, and Apollo vanishes for a minute. “Sorry,” he says when he returns, removing his shearling knit sweater and revealing a Dickie’s work shirt underneath. “I’m just switching hotels, because this room doesn’t have a bathtub.” It’s the day before his first Met Gala (“I’ll be with the girls…I’m always with bad bitches”), and he’s trying to stick to a new routine he’s made for himself, which involves a combination of taking a bath every night before bed and assuming sobriety to preserve his voice. “Alcohol’s really bad for your vocals – it might be worse than cigarettes, in my opinion,” he says. When you drink, he says, you have to worry about acid reflux and post-nasal drip when lying down and, worst of all for the highly loquacious singer, the manic, frenzied talking. “At least when you're smoking a cigarette, you're kind of quiet, you’re like…” – here he puts his fingers to his lips and inhales sharply – “but I only really smoke when I drink, so I figured, if I can avoid the drinking, then everything else will stop.”

Cardigan, shirt, tank top, pants, loafers and belt AMIRI. Necklace TIFFANY & CO.

The sobriety is an attempt to prepare for touring, which Apollo has done with increasing frequency over the last few years. He toured North America with Ravyn Lenae in 2022, performed for the first time at Coachella, and last year was the opening act for SZA, his first time performing in arenas. But when we speak one week later, he’s back in LA and already reconsidering his sobriety. The monastic ideal for touring demands several existential concessions: strict diet, rigid sleep schedule, reducing vocal strain by not talking too much. These are obviously challenging constraints for someone who loves to eat, enjoys late nights, and gets energy from socializing. Being responsible, we agree, is rarely the fun option. And you have to live to make good art.

Being irresponsible, though, is the behaviour his discography inspires. Apollo makes music to call your ex to. “That’s an accident!” he assures me when I say this, and not necessarily an advisable decision, either: “Like, maybe you should listen to something that will cleanse your palette instead?” Still, it’s not a totally undesirable effect. He wants the new music to make people cry. He wants it to help them heal from their romantic wounds, including the ones they didn’t know they had. All his exes know which tracks are about them. His songs echo with the ghosts of boys – his boys, my boys, your boys, our boys. “My whole heart is in every word of this record,” he reflects. “I’ve released all of my attachments to it now. I’m just trying to get through this week.”