Justin Mikhail Solomon in conversation with Curtis Taylor Jr.

The Missouri-based visual artist catches up with Film Director, Taylor Jr. to talk about Black spaces, setting one's own value system and loving our bodies.

This story was originally published in Justsmile Issue 1 FW20.

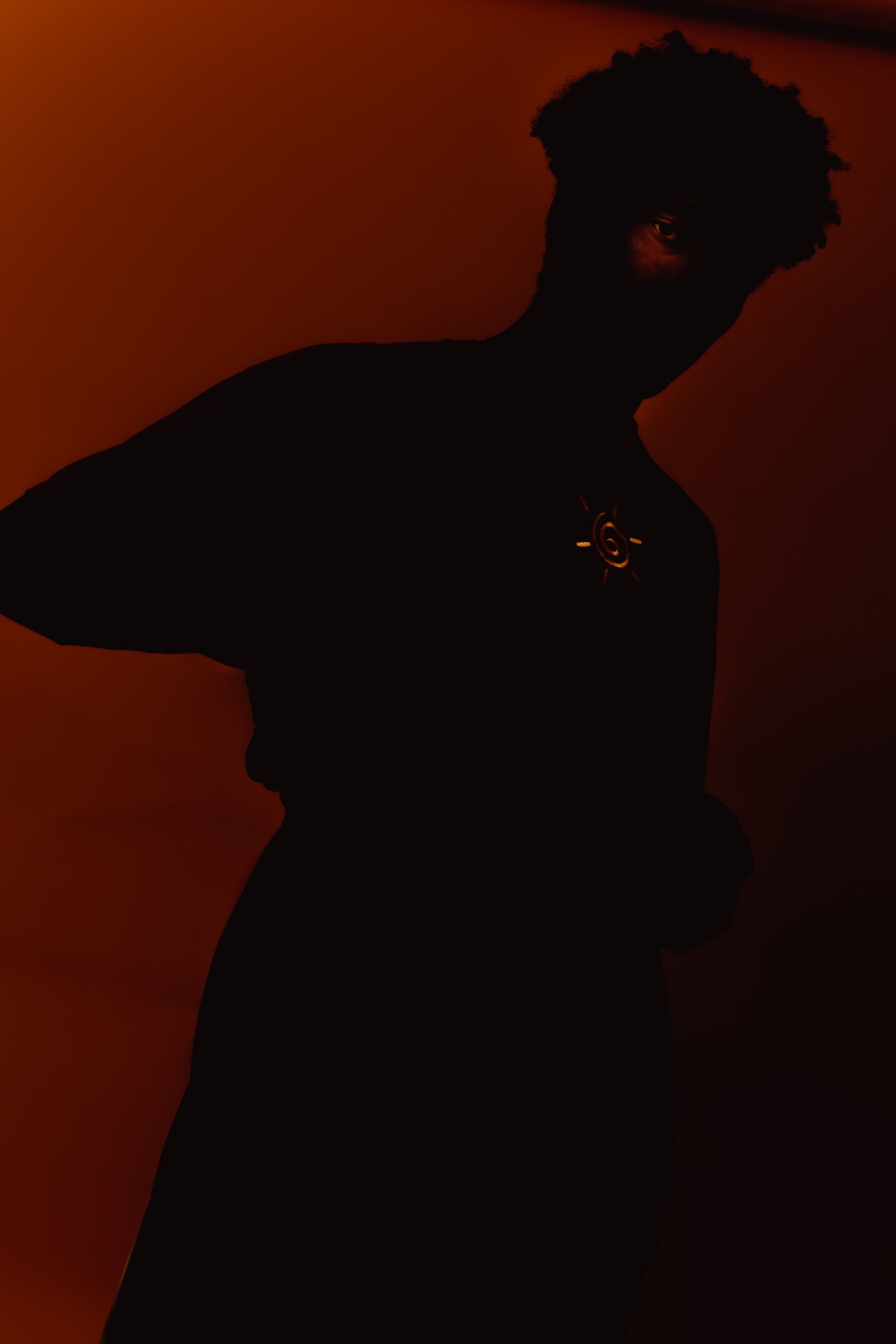

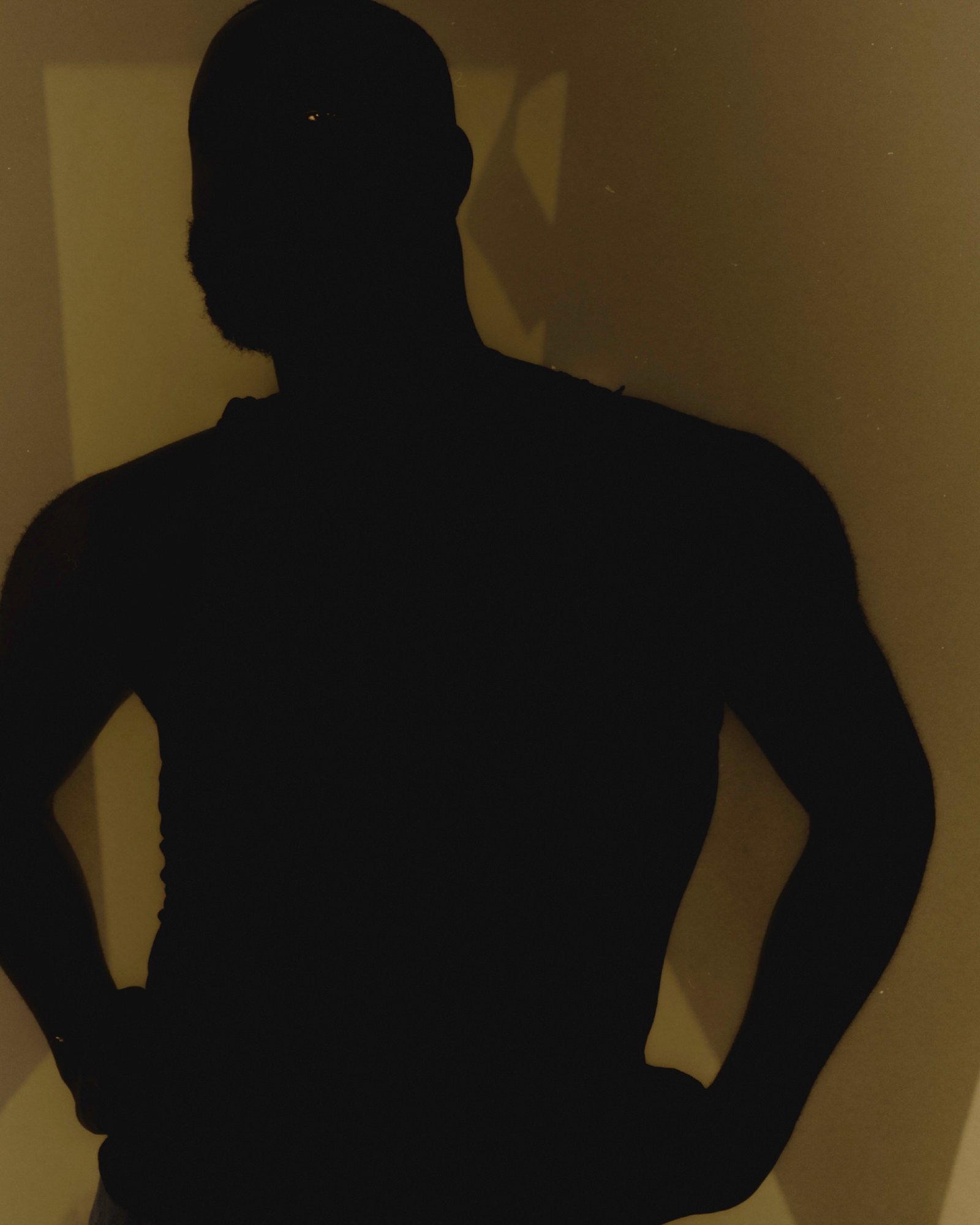

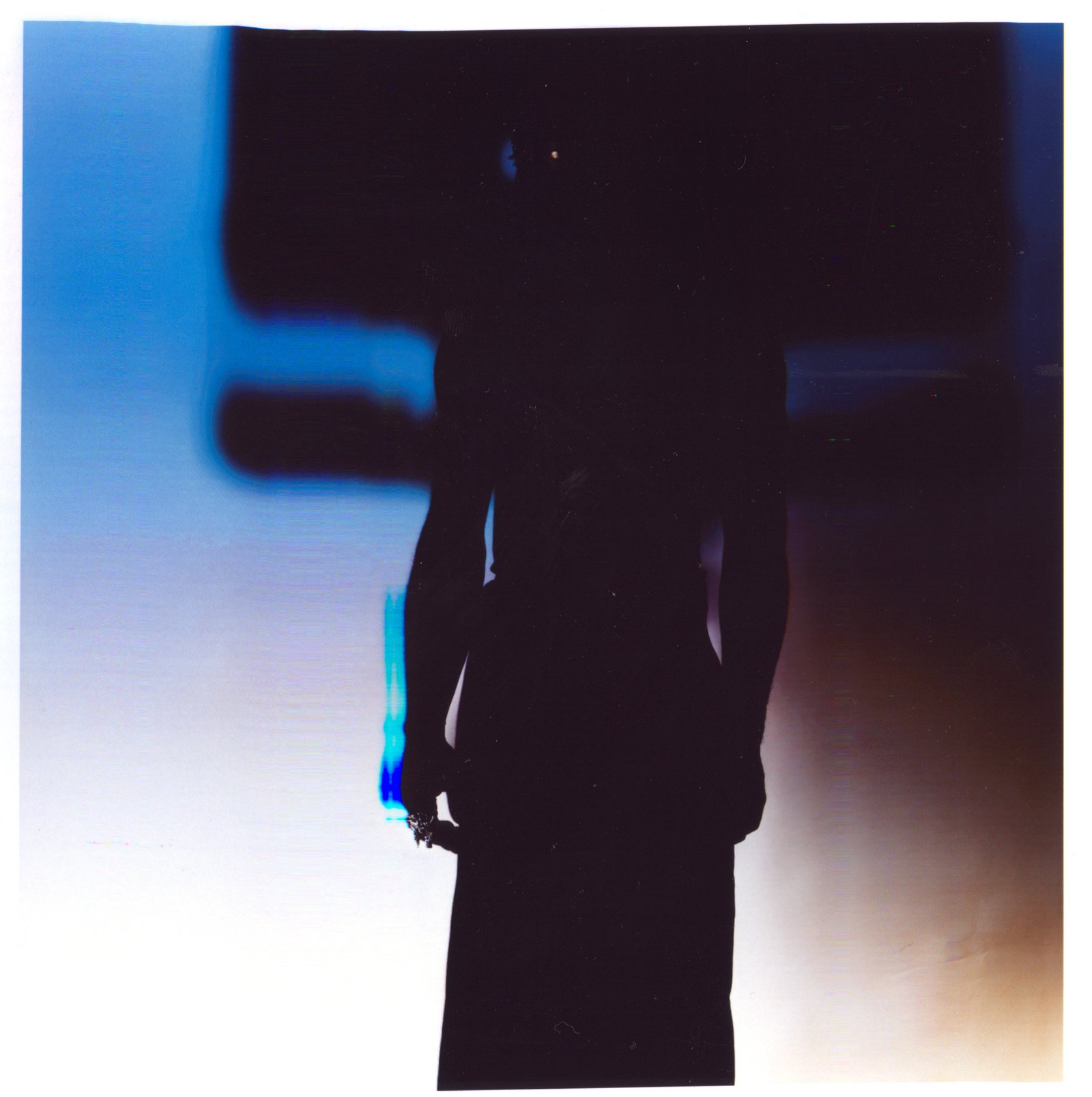

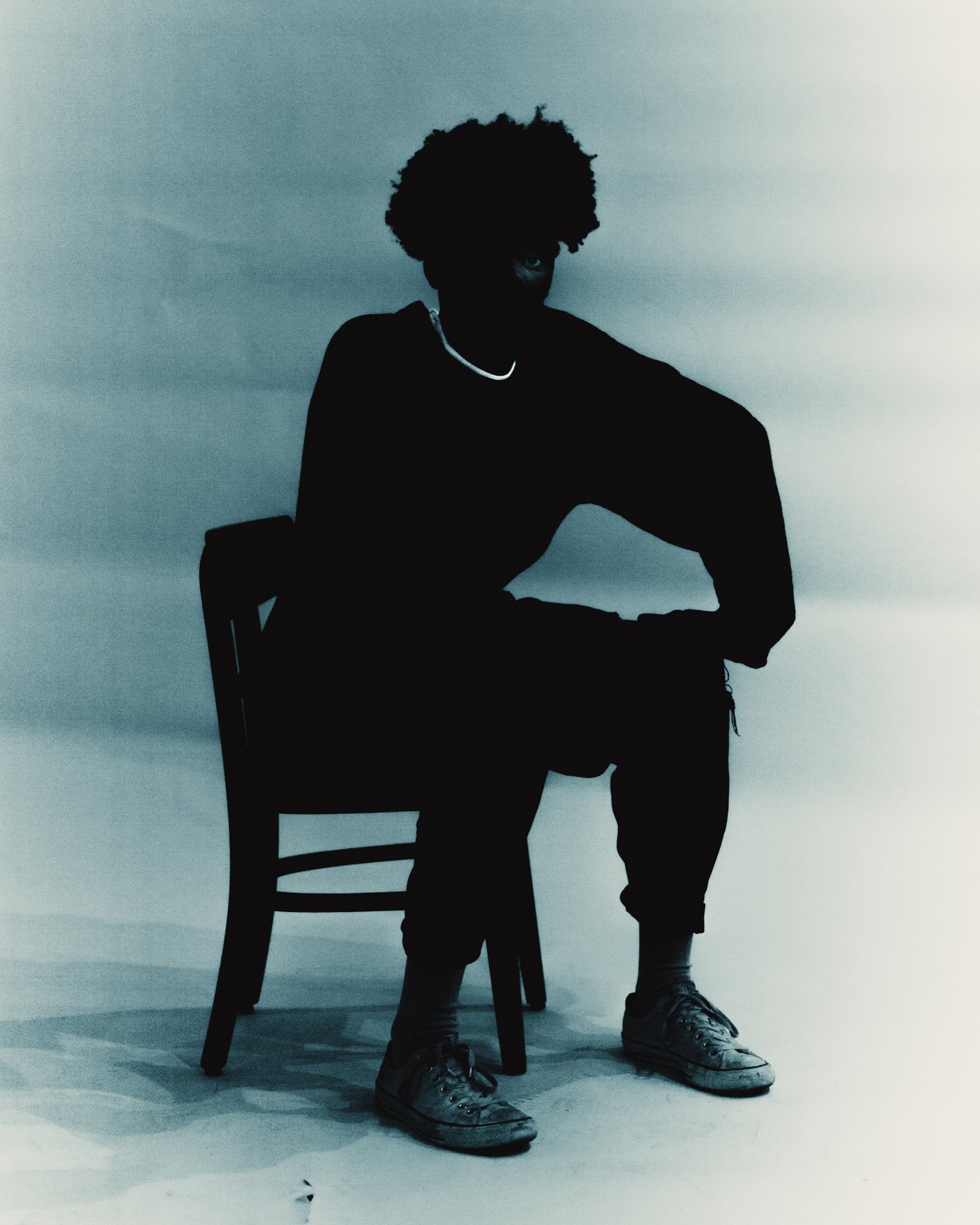

Artwork by Justin Mikhail Solomon

Justin Mikhail Solomon: I guess as a first step, it would be dope to hear you speak about the work that you make, and your journey through your creative process up until now.

Curtis Taylor Jr: Sure, so I'm Curtis Taylor Jr. I consider myself a director and a scholar, but above all those, a Black image maker. I think that for me, I am always trying to do work that nests Blackness at the intersection of fiction, and really sort of begins to build a world where we get the ability to imagine and be the fullest extent of who we are. I would say that is the sort of work that I make.

JMS: Yeah, I think in this kind of way me and you really merge as far as [believing that] artistic purpose is the space creating these realities within reality; especially as it pertains to Blackness. The purpose behind that being that by creating these realities we kind of open up space for, like you say, other parts of ourselves- for the fullest extent of ourselves to be explored.

I guess that kind of segues into how we met… I feel like even though we met in a singular moment, we also kind of re-met each other a couple of different times, because there’s when I first met you- the interaction of, ‘okay, I'm really interested in who this guy is as a person and as a creative,’- but then through the whole Greens saga I felt like I was really meeting you: and seeing all these different ideas you have, come to fruition.

CTJ: Oh, yeah - like you say, creating these realities, within reality: I feel like a lot of that carries over to my work. Especially the work using silhouettes, it’s not only a means of expression as it pertains to Blackness - and the spectrum that exists within Blackness - but also using that aspect of the medium to try to uplift photography as a whole. I feel like we share this desire to not only transpose Blackness and uplift Blackness, but also outside of being Black, there are these goals that we have in our work. Because I feel like it's one thing to be a Black artist, you know, and to make Black work - and this is very important to me - but I think it's also important to really think about the impact you want to have on art as a whole, or your medium as a whole.

Artwork Justin Mikhail Solomon

JMS: Yeah, so in that: I think one of the biggest things or beneficial biggest interactions that I've been able to have with you that has impacted me is like the whole The Greens experience. I guess I'll let you kind of explain what The Greens is since you obviously know more about it than me.

CTJ: Yeah, sure. So The Greens is a concept store and space that was founded by myself and Marquise White in Columbia, Missouri. It was a space that we built as a touch point for the community, centered on streetwear but also at the intersection of conversations surrounding curation, art, and ultimately, life. That's where we really started to work together, but the internet initially brought us together.

JMS: One thing I always loved about The Greens was it was really this space in which anything was possible. It was this really modular space; and one thing I've been thinking a lot about is how modular design is a Black concept. Like, when you think about Black households, there might be one item that has six different purposes, you know? And being in a space like The Greens, and seeing beauty transform from this clothing boutique to this conversation space, to this art gallery. I think when I first started to see that, if you really look at the timeline; that's kind of when my work really started to change, because we met around 2018. And I had just really started doing like the silhouettes and really thinking about photos in a different way. So I was kind of in a modular think space; what could the image be beyond? What it is at the point of capture? But as I look at the timeline from then to now, that was one of the biggest turning points in my work was the Sign show, and I was talking to Justin Leroy. We were talking about the spectrum of Black male identity: what's allowed of Black males, or how it was how we're allowed to be represented. Because at the time, people started photographing people wearing durags, and like, Black men with flowers in their beard; these expressions of Black joy. But from the conversation that we had about what's the next step beyond that, I was able to get to a point in my own thinking of, ‘I want to make images that exist in a space, not only at the extreme of Black joy, or at the extreme of abuse against the Black body or trauma, you know, I want to make work that exists both within this spectrum, and also to explore the farther bounds of the spectrum.’

CTJ: Absolutely.

JMS: I don't really think I would have been able to get to a place like that had it not been for The Greens. Because ultimately, at the end of the day, we want space, to exist in space and have our voices heard and things of that nature. One thing we recently talked about was with your CNN feature; while on one end it's important to go after these things that already exist in the reality we live in. CNN is a big thing, Vogue is a big thing, and you should be happy about those achievements. Still, you know, at what point do we get to set our own values?

CTJ: I mean, to be honest, that's what I think that’s what The Greens was for us. Right? We created our own value system. We realized that these other institutions don't have to validate the work; and it doesn't have to validate our experiences that are tied to the work. I remember there was a time that Adrian [O. Walker] mentioned that he felt like we were wanting to create the spaces that for some was even church: this idea of communal healing. With it being at Columbia, Missouri; that was a space that caused us so much trauma. Where so much Black life was abused. So for us to do it in that space was crazy. Also, I don't know if you ever knew this, but the store’s physical location used to be one of the earliest banks in Missouri, and so the backspace where the office is, it's actually where the vault used to be. And, you know, it was crazy for us to think about: here we are, two young Black men literally making commerce in this space where a Black dollar was once not even allowed in. And then the life cycle; after that time as a bank, it was a floral shop. So when you think about The Greens, and you think about the fact that it was a floral shop before us, it almost seems like from inception it was made for us, and all the things that grew out of it are exactly what you're talking about, right? When you talk about your work kind of like changing in this space. All we wanted to do was to create a space where we could imagine different. I think that all of it was by design, you know, for us to be here right now is no exception to that.

JMS: I feel like that’s some Midwest shit, you know?

CTJ: Definitely. Definitely some Midwest shit. But it just is what it is.

But, so, the silhouette work, it feels it feels so dark, but a part of me feels like it's not dark, so I guess I have a question for you about that.

Artwork Justin Mikhail Solomon

Just because something is portrayed in this dark feeling, in this dark vibe, there is more of a story that’s playing out. You can't just take it as ‘these are dark images, so this story has some scary context or some dramatic context.’ Because the stories don't: they weren't about that at all.

JMS: I would say about that aspect of it; feeling dark. I think - and I've talked about this before - when we look at dark figures, or the color black for instance, from a historical context, it's always been used to portray things negatively. Even when you take the Bible into consideration; God is synonymous with light, so whether or not you say the devil is synonymous with darkness or whatever, that's already implied you know? So when you as a Black man are saying like, ‘Oh, these images seem dark but they don't feel dark.’ That’s a part of the purpose of the work: to recontextualize what it means for a thing to be dark, like just because something is portrayed in this dark feeling, in this dark vibe, there is more of a story that’s playing out. You can't just take it as ‘these are dark images, so this story has some scary context or some dramatic context.’ Because the stories don't: they weren't about that at all.

For example, in the images that I have from the Just Pictures show, none of those images are a response to anything from a negative context: these are conversations I'm having with myself about what it means to be a man, or what it means to exist around my brothers, or exists within a brotherhood...what it what it even means to be Black, what, as a Black man, exists within me, even if it wasn't placed there by me… and how can I go about liberating myself from those things. But none of that's dark: it might be dark in the context that self-exploration can be scary, I guess. What's unexplored is often thought to be in the darkness, too, so there's those similarities, but really, that's why I'm drawn to the work of artists like Kerry James Marshall because we, historically speaking, haven't been at the forefront of our own narratives. So when you look at these images of Black people, or Black figures, there's always this underlying thought that arises in the viewer about what it represents, and oftentimes that comes out in a traumatic way.

Photography as a whole is challenging, because oftentimes people have used light to bring attention to certain things, but why can't you go the other way and use a shadow to bring attention to something? Why can't something almost in complete darkness have as much of a significance is like something in complete light?

CTJ: You know, I feel like real time as we're having this conversation, I'm having to challenge myself and to undo myself right now. Even when I think about Kerry James Marshall, or these artists who have this thematic of shadow play… it makes me think of the word ‘haunting’. But to your point, right, I'm like, ‘Is that okay? To feel the work is haunting?’ And I think another thing I've always wanted to ask is that your work also has this level of intimacy with the black body; have you always loved your body?

JMS: Um, nah, definitely not. Like, I can't even say I'm at a place right now where I love my body: I go in and out of my phases. Some days I wake up and I feel too small, or like, maybe I'm bloated. But I think the way this kind of manifested in my work is, you know, the silhouettes are also this study of form. Even though I've existed in this body for 24 years it feels different almost every day; and that can go in any direction. It might feel bad one day, I might feel really connected to it one day, and that connection might feel scary one day, and another day, it might feel like love. I've always listened, watched others to see how my body should be functioning, or how my body should look. It’s played a really big role in the way I've shaped myself as an adult: the way I function through sexuality, in my romantic relationships, but also in my relationships with friends as well. Not necessarily the appearance of my physical body, but as it pertains to, like my male friends, I am always kind of hyper-aware of my proximity to them in physical situations.

Artwork Justin Mikhail Solomon

CTJ: So let me ask you this question: when you're talking about your body and other people, sometimes, we talk around a thing, but we don't talk about the thing. And it's just like, are we really doing the work here or not? And this work is just as important as the work that's on the galleries, right? Like, this is the work you can't hang on the wall. This is the work that happens in secret, and I say ‘in secret’ because a lot my boys or my brothers feel comfortable with me, I feel like they don't always show this side of what some may deem as ‘vulnerability’ with the outside world. It almost feels like these conversations happen in shadows. So I think about times that should be comfortable, to hug on what might be like my little brother, or you know, my little cousin or whatever you want within that same realm… because of how you might have felt in your body, at times it made you feel uncomfortable for like, hugging you or to love on you, you know what I mean?

JMS: Yeah, yeah most definitely. I think that's the interesting part. Because really, like you say, this is what this is all about, beyond the work. I know, for me personally, I want to get to a space where I can have conversations like this. And if I'm in the space, why am I not having the conversation? Why am I still telling myself what I should be comfortable with, or listening like to these outside ideas of what I should be comfortable with? So, you know, when I hug my guy friends it does feel good, but it’s something I want to just be natural. I want it to just be like ‘Curtis hit me up today. And he told me he loved me so much.’