Shedding tears with Fulton Leroy Washington

Fulton Leroy Washington has been painting on faith for over 20 years; he opens up about gratitude, inner strength, and his signature tears.

This story originally appears in Justsmile Issue 2, Together in the Fold.

Photography Shane J. Smith

Text Leanne Petersen

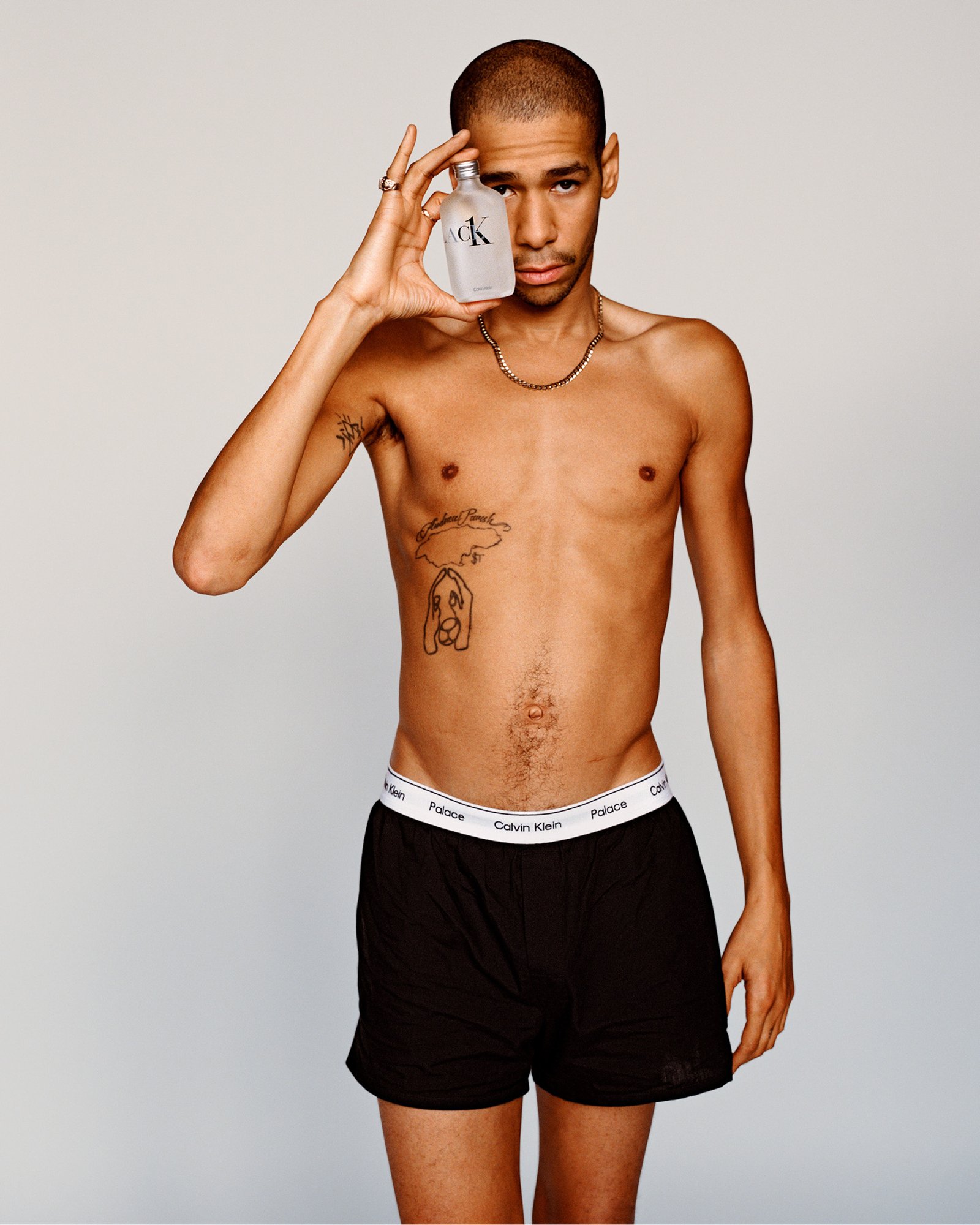

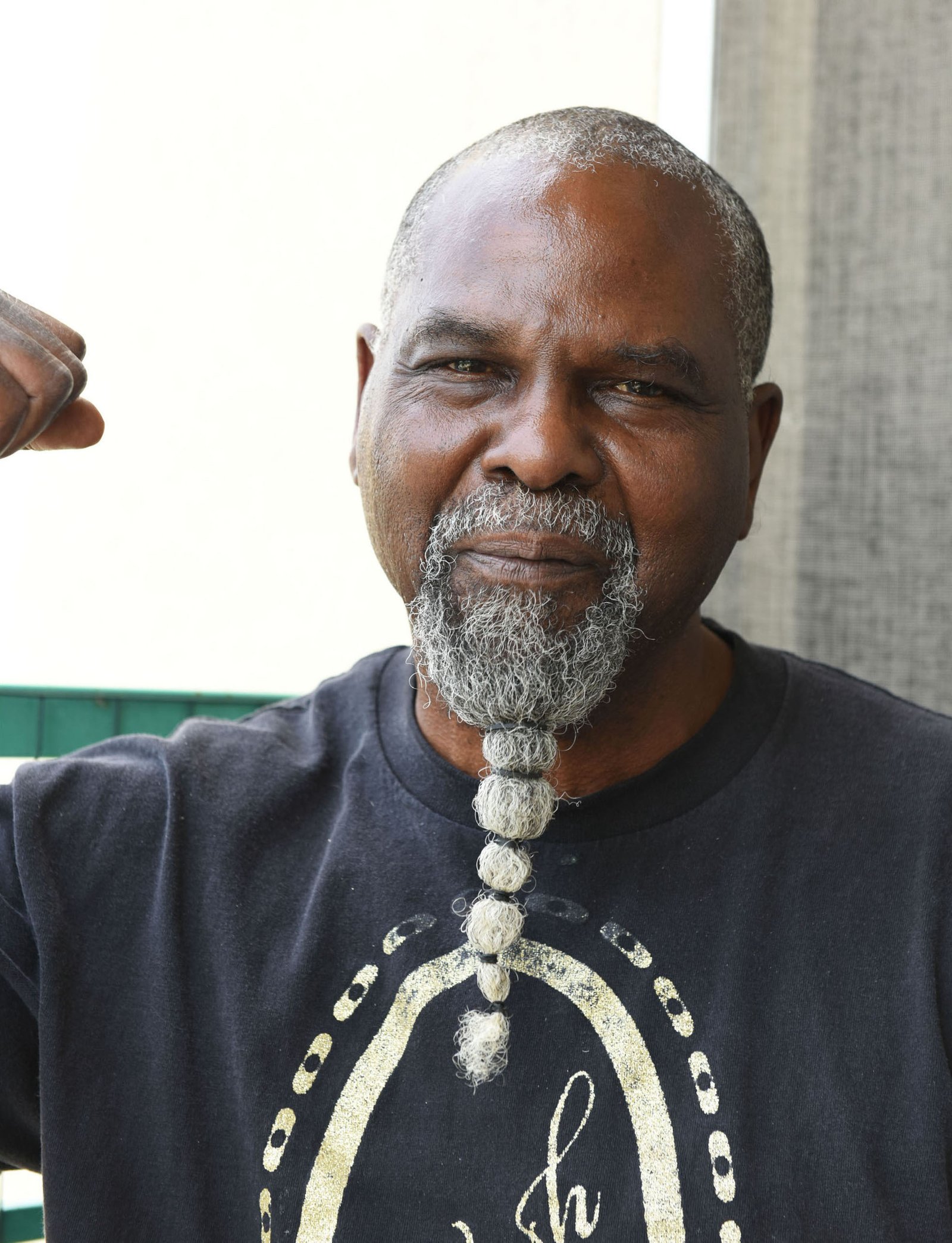

Fulton LeRoy Washington photographed in Compton

Nearing the end of his first museum show ‘Made in L.A.’ (2020) at the Hammer and Huntington Museums, Fulton Leroy Washington (also known as Mr. Wash) is in the midst of a busy schedule. He is currently preparing for his showing at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) ‘Black American Portraits’ exhibition later this year, and artworks for December’s Art Basel in Miami. Alongside this, he is completing several personal commissions for Drake (who he recently met in L.A. after several missed DMs from the musician on Instagram). Speaking via Zoom, Leanne Petersen caught up with the Compton based painter for Justsmile Magazine.

‘Good Morning Leanne,’ Washington greets cheerfully.

‘Good Morning Mr. Wash.’

‘I gotta figure this out, something ain't going right,’ he says, and stands up to adjust his computer screen.

Appearing much younger than his sixty-seven years, Washington’s signature salt and pepper-tied beard suspends neatly from his chin, making him instantly recognizable. Born in Tallulah, Louisiana in 1954, Washington grew up in Watts, California until the riots of 1965 when his mother decided to move the family to the suburbs. In 1997 he was sentenced to life in prison, where he began to teach himself how to paint as a way of coping with the heaviness of his sentence and as a means of keeping in touch with friends and family on the outside. Bill Clinton’s 1994 Crime Bill (commonly referred to as the three-strikes-and-you-are-out rule) meant that Washington’s three prior non-violent drug offenses granted him a harsher sentencing.

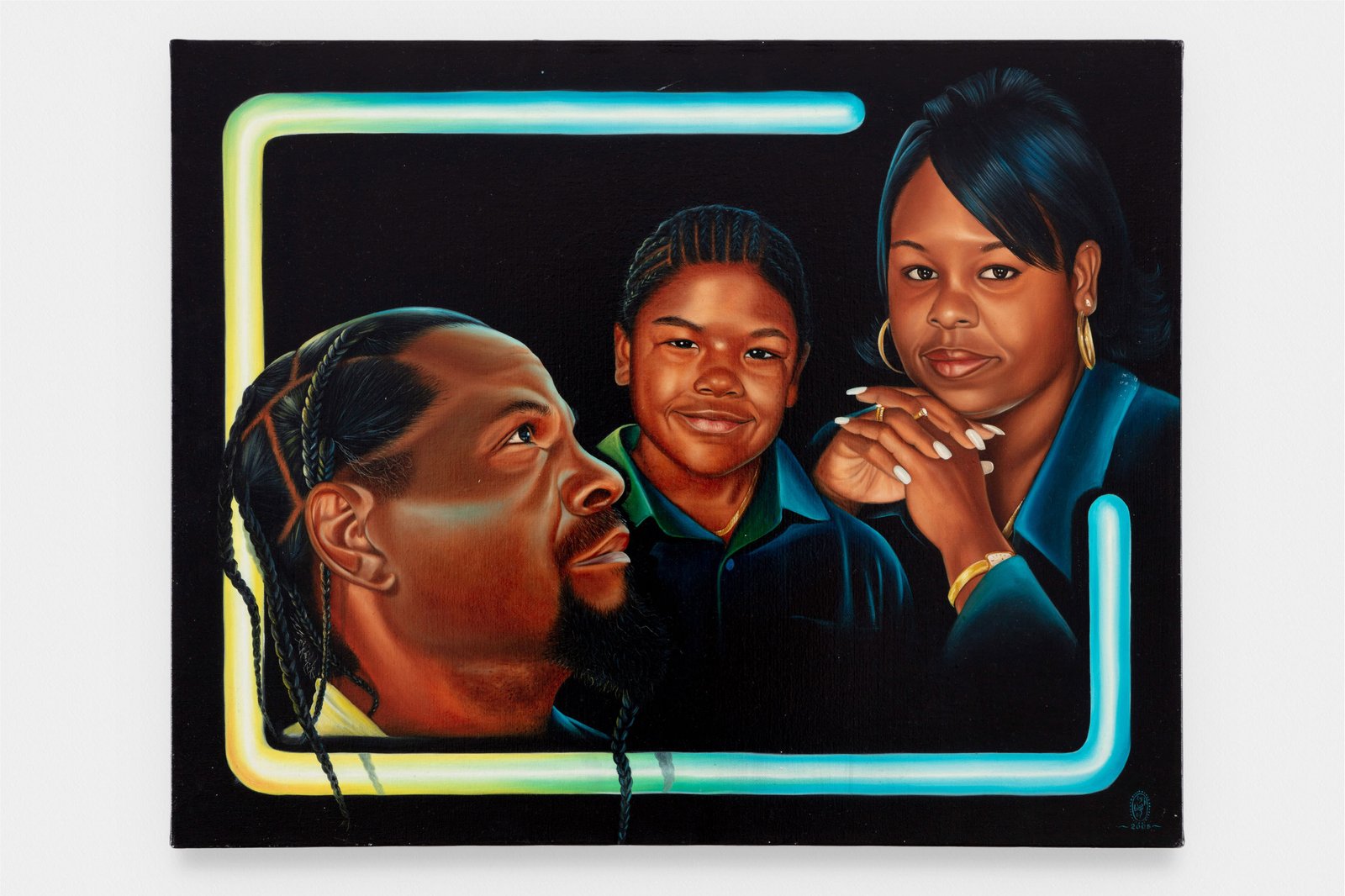

Fulton LeRoy Washington 'NEONLOVE/First Born', 2005

‘Any better?’ I ask.

‘It was okay before…’ he says as he begins to sit down. ‘Oh, I don't like this lighting!’

Washington landed on his photorealist style after observing how his fellow inmates were painting portraits of people in a characteristic style, as opposed to a true likeness. Nevertheless, he maintains alongside the Spanish surrealist painter Salvador Dali, his fellow inmates as being some of his favorite artists, and many from which he learnt the techniques he uses today in his work.

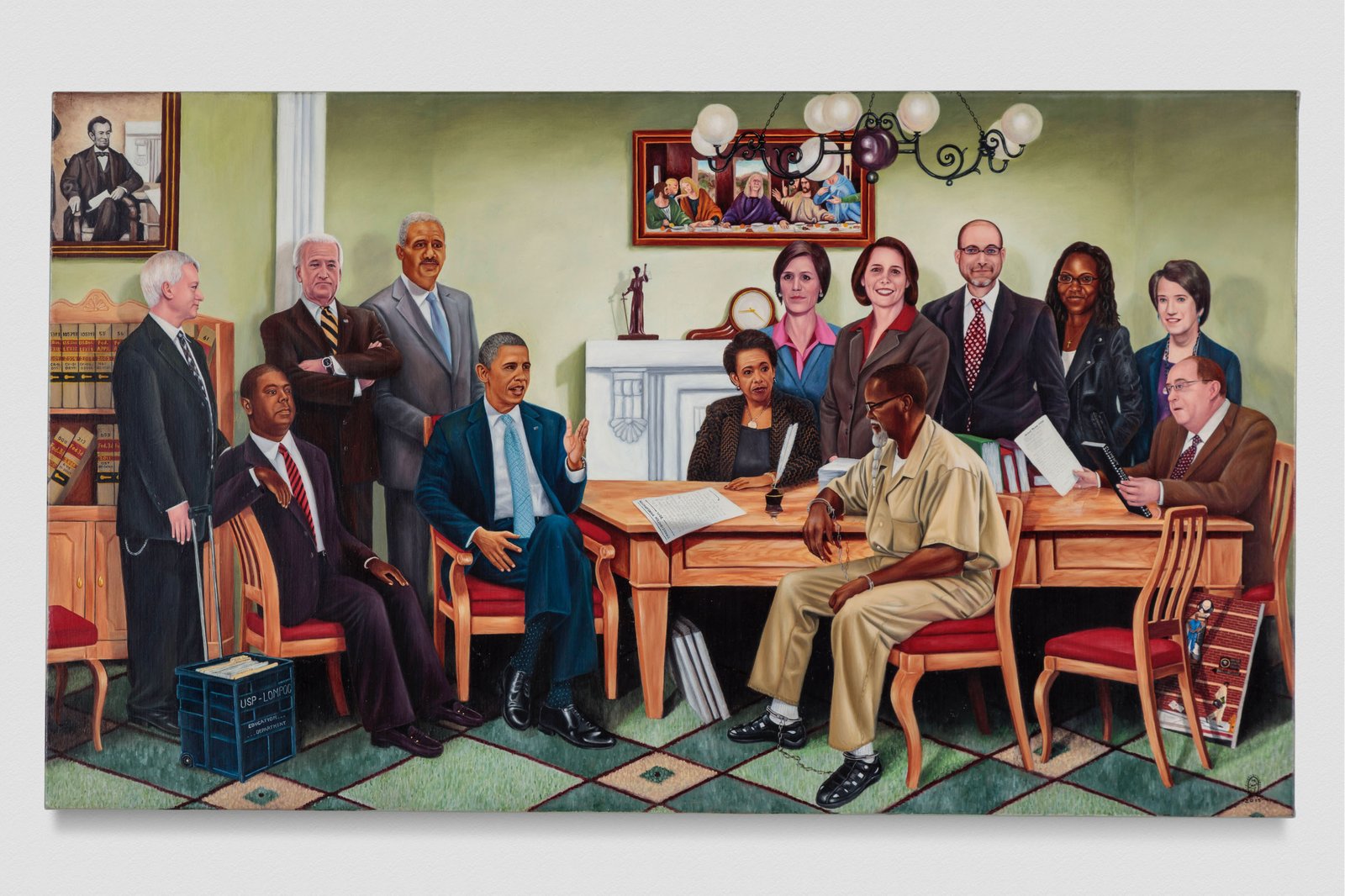

Fulton LeRoy Washington 'Emancipation Proclamation', 2014

Earlier this year Washington took part in the ‘Shattered Glass’ exhibition at Jeffrey Deitch gallery in Los Angeles. The group show featured over forty artists of color including Lauren Halsey, Chinaza Agbor and Jammie Holmes. Amongst his works on display was his final painting produced whilst in incarceration, Emancipation Proclamation, 2014. The image makes an insightful reference to Francis Bicknell Carpenter’s First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln, 1864, which showed Abraham Lincoln and his fellow cabinet members. Washington cleverly exchanges Carpenter’s depiction of Abraham Lincoln with President Barack Obama and places himself as one of the original seated cabinet members at the table. As part of his appeal process, the work journeyed to the White House and eventually led to President Obama’s decision to grant Washington clemency in May 2016.

‘So, are you currently in New York?’ He asks re-appearing on the screen again.

‘Yes, I'm in New York,’ I reply.

‘Yeah, I can’t wait for the opportunity, I got about five weeks and I'll be off federal parole and free to travel.’

Photograph by Shane J. Smith

Despite being released over four years ago now, Washington is still considered a convicted felon and federal inmate. This means he is unable to vote and cannot leave the state or travel abroad without written consent. He continues to work on this case to prove his innocence through the support of donations, and sales from his clothing line WASH WEAR.

‘Okay, let's go, what we got?’ he says as he settles into his chair.

Leanne Petersen: Well firstly, congratulations to you on the success of your recent exhibitions – how does it feel seeing your artwork in galleries and museums?

Fulton Leroy Washington: I'm just grateful. I'm grateful because you know, coming home from prison, my first search was to find a gallery or museum to help me show my work and I was denied by everyone. I’d talk to curators and they’d tell me that it would take anywhere from ten to fifteen years before I could show as a new artist, and I explained to them that I'm not a new artist. I've been doing this for twenty years, but I did it in prison.

LP: Did you ever visit any galleries or museums growing up?

FLW: No, not that I remember.

LP: Do you have any early memories of art or artworks?

FLW: I had a girlfriend who became an art dealer back in the 70s. Now keep in mind, in the 70s. I think our rent was like $149 or $139 per month and she wanted $360 for this print of an eagle holding on to a dead branch in the sand. I don't know what the artist thought about it, but to me it was such a fantastic painting. A golden eagle was holding on to the branch in the sandstorm, all of his feathers were leaning back, and his feet were right in front holding on to this branch, [he was] not gonna be taken away in the wind. I felt all that in the painting, to see the eagle holding on for survival… Even during my time of incarceration, it's those types of reflections that gave me the strength to continue to go on, to continue to fight and not to give up. He wasn't giving up. He was not letting go. I always remembered that, you know.

LP: Do you still have the work?

FLW: No, I did come home to find it but during the twenty years I was gone it got so damaged, water had leaked in the garage, it stained, so I threw it away.

Photograph by Shane J. Smith

LP: Tell me about your process, how do you like to start your paintings?

FLW: I begin to work first by listening – listening to either the inner self, or, if someone else is talking, the words always make images in my mind.

LP: Faith seems to be an important part of your life and practice.

FLW: It's all that I have. Every painting I do, I just put a blank canvas up, I pray then act. See the things that I do in this life are not so much really for me, but for the people who receive it after God works through me.

LP: How important is the scale of your works?

FLW: It's not.

LP: It's not?

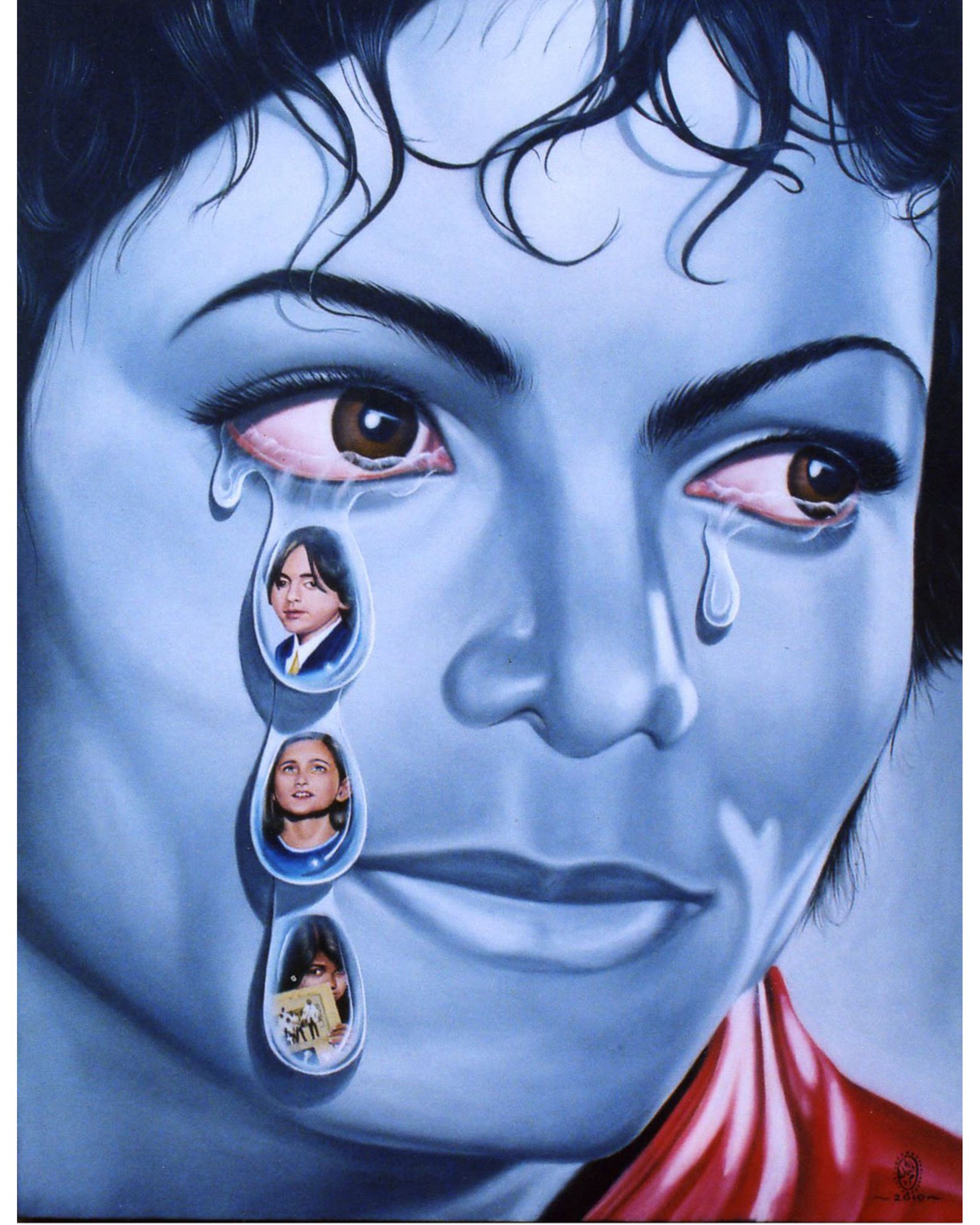

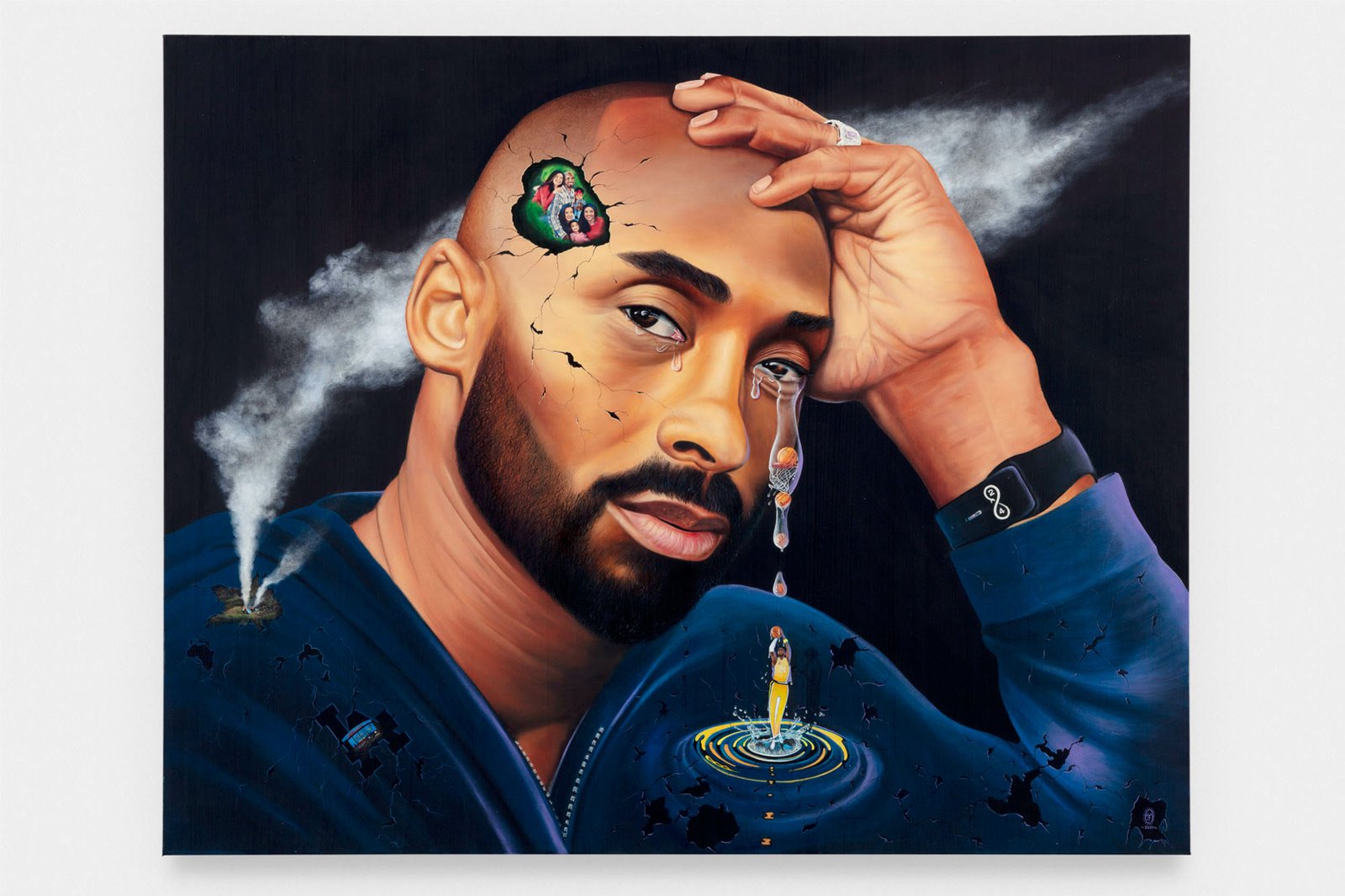

FLW: It's irrelevant. I mean, if you look at the pictures that are on display, now [at The Hammer Museum and Huntington Library], the teardrops that I paint. Some of those faces in the teardrops will fit on your fingernail, on your small fingernail. That's how small they are, and then the faces are 300 times, 400 times larger. I can work at any scale; what's important is the composition, you know. When people come to the gallery they walk into the room and the picture draws them in. No matter how close you get, I've made sure that the detail is as close as I am to the painting, in order to see it. So, it's like looking over my shoulder. But once you do that, you're no longer seeing the big picture, you're inside the painting. I take you in, that's what I do with scale.

Fulton LeRoy Washington 'Michael Jackson Tears', 2010

LP: Can you tell me more about your signature teardrop? How did you begin using these in your works?

FLW: The teardrop started with Tim McGraw…

*At this point, Washington begins to play the song ‘Grown Men Don’t Cry’ and becomes tearful. He gets up from the computer and steps out of the room. He returns soon after the song has finished, and we continue.

LP: You became quite emotional once the song started playing…

FLW: Yeah, that's how it started. I didn't have a radio [in prison] – I gave my radio away and I had stopped watching TV. It had been over ten years since I watched TV or listened to the radio and this guy was in there painting with me, my buddy and fello artist Cal [Calvin Triber]. He always had his earphones laying down and, you know, just playing music while he painted. That song came on and made me reflect about my wife and my children being at home alone. I started crying, I couldn't stop, I had to hold my mouth in order not to let it come out because I'm in an institution where if you show any kind of weakness, you become prey. I had to pull my canvas in front of me close like I'm busy working so as not to let them hear me cry. When I made it through the song, I was able to get myself together, my eyes were still red, which they always are from welding for so many years. I went back to my unit and drew a sketch of myself and all those emotions.

The next week I took the picture into the yard and I painted the picture. I painted the tears, and I painted the thoughts inside the tears. That painting triggered not just the inmates inside the hobby shop working with me. I had also showed my students, the warden, and all the staff; everybody had so much vulnerability and emotional stuff they were going through.

I am not strong enough to cry in front of everybody, but I cry in the silence of the dark, you know. Even in prison you hear people cry at night. You don't know exactly who it is because everybody's in their cell, but you hear them whimpering – a grown man when they come out that door, chest out, all buffed up, ready for whatever the world has to offer. But in the silence of the night, when I would be reading my legal work trying to figure out how I was going to get out and get back to real life, I’d hear them crying and then slowly one at a time they would come and ask for permission to be inside the art room, and they would tell me their stories and ask me to create paintings.

There was a constant list, up to two years’ waiting period to get teardrops. People had a lot of things that they cared about. Sometimes it was just animals. Sometimes it was their mom, or their cars, some it was their girlfriends or wives or children. But yeah, that's how it started, the same way it is was when I hear the song now. I don't know why they say ‘men don't cry’ – I painted that.

Fulton LeRoy Washington 'Shattered Dreams', 2020

LP: Has working from prison to now working from home had any effect on your practice?

FLW: Oh my God, it's like two different worlds. In prison I probably had 35 or 45,000 square feet of space, I had a warehouse and that was my space that I also taught in. We had unlimited amount of tools and you never felt crowded. Here, every time I get ready to go from one exercise to another it's maybe fifteen or twenty minutes just to re-adjust the furniture [equipment]. I was able to create more artwork in prison, over 100% more.

Photograph by Shane J. Smith

LP: What do you hope viewers will take away from your work?

FLW: I want my viewers to take away that there's a lot of voices in the world that's not being heard, and when you look at my art, when you examine my art, these are the voices – the unheard voices of the people who didn't have a voice, that couldn't say what they were feeling. So, my art is a translation of those voices, but also what's going on in the world at this time in history.

Fulton LeRoy Washington 'Mondaine's Market', 2020

My art represents what's going on now, as a reminder, because if you depend on the news and the media and the history books, they will distort the truth to their political advantage. My art just tells it like it is, so that's what I want the world to get from my artworks. These are not my voices, but these are the spirits and voices of those that cry out. I just thank God that I'm a receptacle that can hear Him and speak for Him in this form of art.